“I just love old things,” says Henry Labouchere, reflecting on two of his great passions parked side by side in the sunshine on a remote Norfolk airstrip.

The tiny Austin 7 and, in aeronautical terms, equally diminutive de Havilland Tiger Moth belong to a bygone era, representing simple mechanics, and bags of fun.

We’ve principally come to talk about the Austin, which has been in Henry’s family since 1955, and in which he thrashed about the family’s farm from the age of eight.

But the 1942 Moth, which he bought in Australia in 1971, is an equally important example of how he cherishes wonderful, veteran machines – as well as symbolising an extraordinary life in the air.Henry was flying solo before he had his driving licence, and has flown all over the world in a variety of aircraft, including more than 100 Moths, regularly taking flying holidays with his wife Jill in Australia, New Zealand and Africa.

Movie legends

He has worked with movie legends including Harrison Ford, David Niven and Christopher Reeve as engineer and pilot on films including A Bridge Too Far and Hanover Street, and has spent the past 40 years involved in every area of aviation other than a commercial pilot.

Brought up “underneath the end of the runway at Sculthorpe”, near Fakenham, when “the sky was full of planes”, Henry’s father was a colonel in the army and his mother, known as Peg, was an “amazing woman” who competed in international rallies like the Liège-Rome-Liège in the 1930s.

He was, therefore, always destined to be adventurous and, you suspect, if he had been born 60 years earlier, he would have found a way to be involved in the very birth of manned flight.

The little Austin came into his life when he was six years old, when his father Peter bought it for Henry’s older brother, John, who was 17 at the time.

It quickly became known as ‘Wam’, because the horn made a sound like a lamb – a word young Henry could not say.

“It cost £50, and I know it was £50 because it was a bloody rip off – it should have been £5,” he says. “ It was very expensive. Jack Bridges (the seller) had my father’s leg up.”

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

Written off

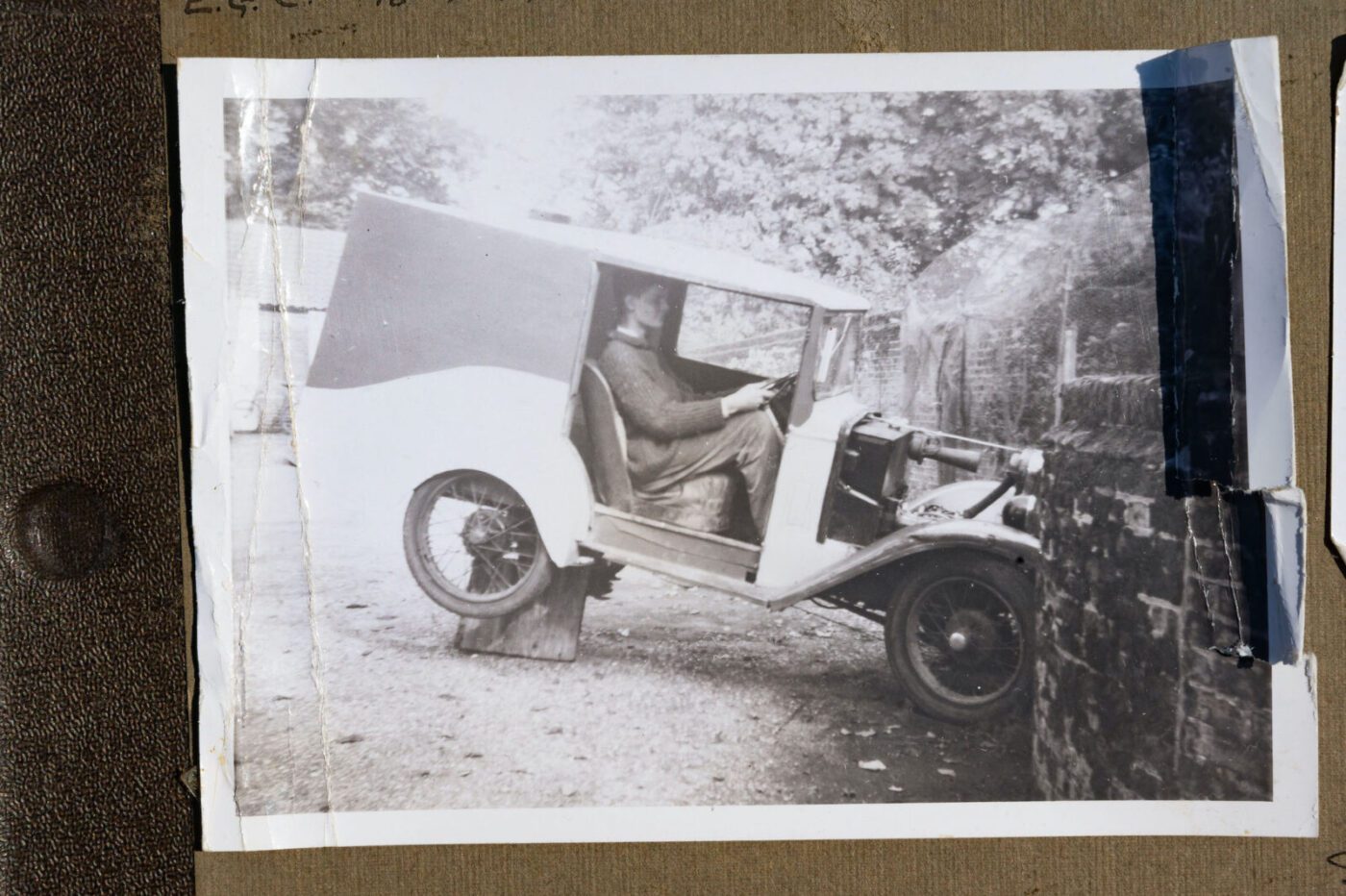

Originally a saloon, and dark blue in colour, John drove the car for about a year before rolling it, writing off most of the body.

“He then spent about half a year rebuilding it as a van, and he made a very successful job of it,” says Henry, sitting in his office, a portable cabin behind his hangar.

“John used to drive it to Norwich every day, carrying his woodworking tools in it, but then eventually he got an A30 Countryman, and this got shelved and put in the shed.

“Then it was tarted up so that it ran, and it was given to me for probably about my 8th or 9th birthday. I remember being so excited having this thing, it was just wonderful.”

The fun lasted for about four years, as Henry “continued to wreck it”, hurling it around the 70-acres of farmland attached to the old rectory in Sculthorpe where his grandfather previously served as vicar.

In about 1963, Henry “sold” the car back to John for four sheets of marine plywood – he was building a boat at the time.

“He rescued it, and took it off to his houses where he lived in Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, and it languished until his son, who’s now nearly 60, decided to ‘restore it’, which involved removing every single bloody nut and bolt off it and losing them,” says Henry.

“Absolutely hopeless”

“So, bless his socks, the bits all lay around, wherever my brother lived – the body, the chassis, the engine, which was lying in a shed with water running in and out. It was all absolutely hopeless. He was going to restore it ‘one day’.”

Meanwhile, Henry was off having adventures around the world, after leaving school “under a little bit of a cloud”.

“There was a bit of a misunderstanding about some detonators on a railway track, and also there was a tractor that went missing, and a lot of it got attributed – quite unjustly – to me, I’m sure,” he smiles.

Sadly, Henry’s father died in January, 1964, and he returned from his final school in Devon to live alone at the age of 16 in the family home after his mother went to live in Shropshire.

“I’m the youngest of four, and my brothers had married and gone and my sister was in Canada,” he says. “So I was home alone with Ford Zodiacs and things to run around in.”

He also learned to fly solo at the McAully flying group, where his mother had also flown.

After agricultural college, Henry started work as an apprentice outboard motor engineer, moving on to work for Westwick Distributors at Ludham, a crop-spraying company operating six aircraft across East Anglia.

“I was engineer, marker, and loader of all these wonderful chemicals like metasystox and malathion,” he remembers. “Of course, in those days there was no health and safety, all you had for protection was a pair of shorts and a bottle of Ambre Solaire.”

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

Life Down Under

In 1969, aged 21, he got a cheap ticket to Australia, starting in Perth painting white lines on the highway, followed by a stint driving loading trucks for a crop-dusting company.

The Mini Traveller he’d bought in England went with him to Australia, and he drove it across the vast and desolate Nullarbor Plain to South Australia.

“I did about 300,000 miles in that car in Australia,” he says, now on the lookout to buy one for old time’s sake.

He earned enough money to buy the Tiger Moth for about £1,200 in 1971, and flew it all round Australia before moving to New Zealand and doing the same there, taking on a variety of engineering and flying jobs to keep afloat.

“I worked with the most amazing people – the can-do-ism, the money you made – it was absolutely wonderful,” he says.

One of them, Arthur Heath, contacted him after he had returned to England in 1976, and said “psst, want a job?”

The job was working on A Bridge Too Far, the 1977 war film with an all-star cast including Sean Connery and Michael Caine.

A host of other films and TV shows followed, including Hanover Street with Harrison Ford, The Aviator with Christopher Reeve, and A Man Called Intrepid with David Niven, “a very wonderful man to work with, so funny you could hardly work because you were laughing so much”.

After marrying Jill, who also has a pilot’s licence, he set up an aircraft maintenance business in the hangar adjacent to the old RAF Langham runway where the Austin now basks in the August sun.

Austin in bits

Sometime around 2010, Henry paid a visit to John, who had returned to Norfolk and was living on a farm near Dereham, with the Austin in bits and scattered about.

“I went to him one day and said ‘J, I won’t give you any money for it, but I’ll tell you what I’ll do…I’ll take it away for free,” he says, laughing.

“Then a great friend of mine, David Wall, comes into the formula. David is a car restorer over at Wroxham, and he’s a fantastic bloke, a real Austin 7 genius.

“We worked a deal between us, it went into restoration and it came out restoration, and here it is.”

Given the car’s chequered past, Henry was unconcerned with originality, so it was converted into a tourer – it’s third body style in 90 years of life.

The 747cc engine and gearbox had already been changed when the car was one year old, the three-speed box swapped for a four-speed introduced by Austin in 1932.

“It’s got the same registration, same bonnet, wings, engine, and radiator, but the body is actually from an Austin 7 from up in Northumberland that had its back end cut off to tow a lawnmower,” he says.

“It’s all made out of Austin bits, and it’s all done properly, but it’s not matching numbers. It’s a practical motor car.”

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

Bright blue paint

Its bright blue paintwork came from a spell working with Gordon Murray on the lightweight OX truck, designed for use in the developing world.

“I saw a car at Gordon’s place in this garish sort of blue and I said ‘I want to know what that is’, so one of the boys found out and said ‘it’s Porsche Riviera blue’,” he says.

“I said ‘well that’s what I’m going to paint my car’. I thought I’d messed up until I put the black bits on, but it looks all right now.”

After roughly half a century, the old Austin was back on the road but, at first, Henry “just put it on a pedestal and looked at it and polished it”.

“Then I thought ‘well, there’s no point in having the damn thing if you don’t use it’ – the battery went flat and things like that,” he says, his early drives bringing back memories from his youth.

“Funnily enough, it was more about the smells. The way the engine sort of fumes into the cockpit brings back more nostalgia than probably anything else. I’m rather sad it hasn’t got the van body, but I can’t have it all ways.”

John was equally delighted to see the old car back in one piece, having become so used to seeing bits of it lying about his farm.

“He’s driven it since, and he’s absolutely thrilled to pieces,” says Henry, a father of two daughters. “He’s an old boy now, 87, but he loves it.”

And he’s not the only one; eldest granddaughter Gabriela, three-and-a-half, “adores it”.

“She jumps in and she sits on my knee and she steers it where she wants to go,” he says. “It’s the first car she ever drove.”

Guy Martin loved it

Then there are the people Henry encounters on his regular runs around north Norfolk, as well as a well-known man more used to driving speedier vehicles.

“Guy Martin was down here a couple of weeks ago unveiling our Spitfire plaque,” he says, referring to the replica fighter plane that looks down on the second world war era Langham Dome, a now-renovated training facility for anti-aircraft gunners.

“He drove it and he absolutely loved it, but it won’t do 200mph so it’s not on his bucket list…

“It gets more attention than an F40 Ferrari. If you pulled up in a brand new Roller down at Morston, you’d get more people looking at the Austin 7 than you would the Roller.”

As I discover when tentatively manoeuvering the car into position for our photoshoot, there’s a knack to driving a pre-war car, and Henry admits it has its limitations – but also its great strengths.

First, there were the lights, as Henry found out when taking the Austin – top speed, 40mph – on a trip to Bury St Edmunds one New Year’s Day.

“Unfortunately by the time I got there it was time to come back, because I couldn’t operate it in the dark as the lights pulled more power than the generator put out,” he says. “You could only put the lights on when something was coming…it’s got LEDs now, which are all right but not brilliant.”

Then there’s the braking and handling.

“There is a middle pedal, but it’s not frightfully effective, I have to say,” he says. “It’s just how they were. As my dad said ‘every child should have one to teach him anticipation’.

“You have to work at it. It is a challenge, you can’t just cruise along with the cruise control on, automatic braking and all the rest of it. It jumps all over the road.

Automotive Tiger Moth

“It’s an automotive Tiger Moth really. It’s just as appalling, the Tiger Moth is an appalling aeroplane to fly – that’s why it’s such a good training aircraft.”

And the car’s strengths?

“It’s completely reliable,” says Henry. “You only touch the button and it goes. If you’ve got a spark, you’re in business.

“It is a great piece of kit and the gearbox is dead simple – although the ratios are appalling, from third to top the thing nearly stops.

“It’s also fantastic off-road. It’s got huge ground clearance, very narrow wheels and it’s brilliant in mud and snow. I used it in the snow when it was really quite bad and the Golfs and things wouldn’t go at all, they just sat there and spun, but this thing was roaring along.

“I also use it down on the coast road because it’s a metre narrower than all the 4x4s, with the boxes on the top with all the tourists in.”

In the 1920s and ‘30s, the Austin 7 was to British motorists what the Ford Model T was for Americans – an economy family car for the masses.

These days, cars of this vintage are rarely seen on the road but, to Henry, it’s just a car to be used.

“I use it probably three times a week to go home and back, which is three miles each way,” he says. “It’s 90 years old, but it actually stays in better nick through my driving it. OK, the kingpins wear out and I replace them, I put new bushes in, I do the suspension, grease the propshaft, change the oil, and change the back axle oil and gearbox oil.”

Part of the family

Just like the Moth, which he says he’s finally got just how he wants it after 50 years, the car is a huge part of the family and will remain with him “until somebody boxes me up”.

“I don’t know what my wife will do with it, but I hope she passes it on to my daughters and the grandchildren,” says Henry. “I think they’ll love it. I really hope so.”

One final question: what does the baby Austin mean to him after all these years?

“It’s just a wonderful thing to have,” he says. “If you knew the pleasure of driving down the Norfolk lanes of a summer’s evening at 7 or 8 or 9 in the evening, getting beetles in your teeth, it’s just great and every time you drive it you get out of it with a smile.

“You always think ‘oh, that was fun’.”