Few of us can lay claim to coining a new word, even fewer to starting a whole motoring belief system.

But when journalist James Ruppert first used the term Bangernomics in the pages of Buying Cars magazine back in 1989, he achieved both.

A movement grew up around the simple principle of buying cheap bangers and scrapping them when they die, avoiding the evils of depreciation, servicing and repairs.

In other words, not wasting money on cars.

So when, in 2010, James decided to have the Mini Cooper he bought for £200 in 1979 professionally restored, something had to give.

With the bills piling up – £20,000 worth over three painful years – he began to doubt his sanity as he rode roughshod over his own rules of automotive frugality.

“Irritating beyond belief”

“It wasn’t good – it did affect my mental health,” he says. “It really annoyed me, it was irritating beyond belief. What am I doing? Why did I ever start doing this?

“At heart I think I’m quite a mean person, and when you see money being spent, you just think ‘it’s just a Mini, how has this cost so much?’”

His angst even inspired a book, My Mini Cooper: Its Part In My Breakdown, charting not only the story of his Cooper but the history of small cars as a whole.

So why did he do it?

“Because it’s been with me a very long time,” he says. “It’s a car that I will keep forever, it’s not going to go anywhere.”

And also because it’s a Mini, a subject on which you feel James could wax lyrical for hours.

“Minis were just spectacular cars,” he says. “It’s just a joy to drive. You don’t have to drive a Mini very, very fast to enjoy it.

“I’ve been very lucky that, over the years, I’ve got to drive supercars, but they’re not remotely as exciting as that. You can throw a Mini into corners at 30mph and it feels as though you’re doing a million miles an hour.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“It’s just fantastic”

“Everything is drama about it, it’s great, it’s got noise, it’s purposeful, and it’s just fantastic. It’s such an exciting car to own. If someone ever said I’ll give you a Lamborghini for that I’d say no, what’s the point of that? It wouldn’t be as much fun, it would be a dull day out. And everyone would think you’re a tosspot.”

No offence to all you Lamborghini drivers reading this…

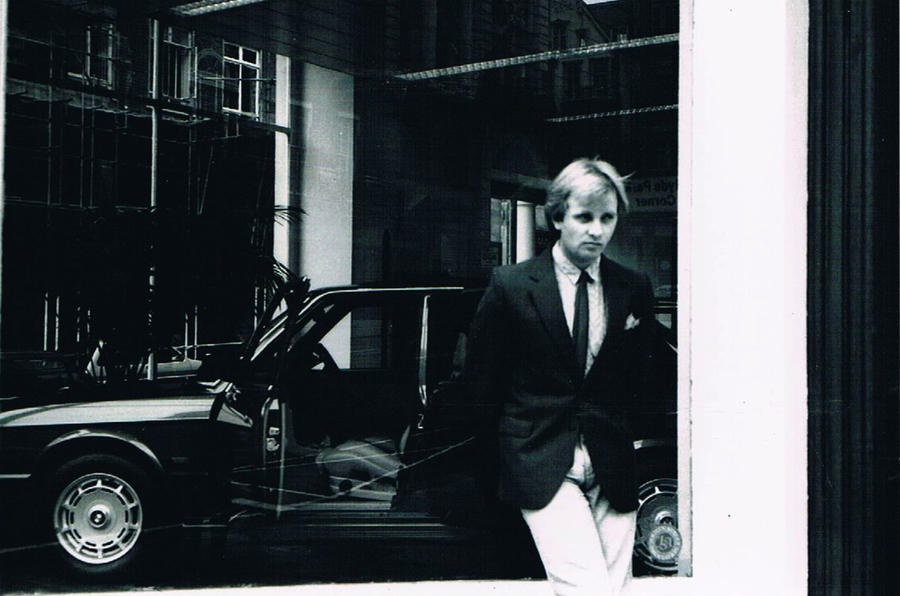

We’re chatting in James’ conservatory at his home in rural Norfolk, about Minis, yes, but also about selling BMWs in the ‘80s, becoming an author and journalist, and the birth of Bangernomics.

Born in East London in 1960, he spent his childhood watching the cars go by on the A12, which ran alongside his house in Wanstead.

“I used to sit on the wall and my mum said I knew every single car before I knew anything else in life,” he says. “That’s a Consul, that’s a Cortina, that’s a this, that’s a that. There were just cars everywhere.”

It sparked a lifelong passion, but James would first work in a merchant bank in the City, then undertake a law degree, before cars became a way of earning money as well as a hobby.

After deciding it would take too long to start earning proper money in the legal profession, he applied for a job that promised a company BMW and on target earnings of £20,000 a year, a tidy sum for a 23-year-old in 1983.

Selling BMWs

To his surprise, he got the gig, selling BMWs at the company’s flagship Park Lane showroom in central London.

“I didn’t really expect to get the job, but I think what they like about certain people is that they weren’t like car salesmen,” he says. “I obviously wasn’t like a car salesman, but it turned out to be the best job I’ve ever had.

“It was spectacular. I can’t tell you what brilliant fun it was, it was just the best time ever.

“All the people you worked with were fun. You’d be in traffic and someone would hit you from behind, and it would be one of the other salesmen because that’s what they would do, as well as handbrake turns into car parks.

“It would be frowned upon now, it would be considered terrible, but it all contributed to everybody getting on. But there were also fights over whether you had spoken to a customer first – physical fights. It was full on.”

James’ time at Park Lane coincided with the rise of the yuppie, and the brilliance of the early 3-series BMW.

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

“Another planet”

“When I drove BMWs for the first time, it was like going to another planet,” he says. “The cars were so unbelievable, and that’s why people will pay a premium.

“And they wouldn’t break down. I never had one breakdown, ever. You’d speak to people at other car dealers and the whole day was ‘I hope a customer doesn’t ring up’.

“People were part exchanging 2002s for a 3-series, and they were only worth a few hundred quid. You look back and think ‘if only I’d had a barn and I could have stuck 2002s in there’.”

By the time he started work at Park Lane, James had already owned his 1964 Mini Cooper for four years.

It was his second Mini, the first an 850 bought from his sister for £50, although “she claims to this day that she gave it to me, but she didn’t”.

In 1979, there were dozens of Minis for sale in Exchange & Mart, and James travelled out to Maidenhead to look at an almond green Cooper, driving it home after striking a deal at £200.

“People weren’t that bothered by them at the time,” he says. “It was just a knackered Mini, that’s all it was.

“The fact that it was a Cooper was actually a downside because it made the insurance more expensive. That’s why people would say ‘no, I’ll just buy a thousand or an 850, what’s the point in paying just for the name?’ That’s probably why a lot more Coopers died, people just got rid of them.

“Stupidly, I could have paid £50 more and bought an S, but I probably didn’t have the £50. I should have bought an S, shouldn’t I?”

Cooper in a state

While the Cooper had an MoT, it was in a bit of a state and “extremely rusty”, so James set about doing it up in his parents’ garage while taking the train to and from work in the City and, later, to the Polytechnic of Central London (now Westminster University) to study law.

“I rubbed it all down and replaced wings and bits of the floor and things like that,” he says. “I wasn’t frightened of doing things. I’m a product of secondary education, where you went to a school and they taught you how to weld.”

He even resprayed the car himself, and had pretty much got it finished just before starting work at Park Lane.

“Then I stuck it away in a garage because I had company cars after that,” he says. “So I did all that work, and it was all pointless because it just sat there and got rusty again. It was daft really.”

The Mini spent many years in lock ups as James moved first to Wembley and then to Ruislip, leaving BMW after two years and driving a succession of Golf GTis, “the Mini Cooper equivalent of the ‘80s”.

“They were remarkable cars, practical, fast, and the Mini was sort of forgotten about, which I feel very bad about now,” he adds. “By the time I was interested in it again it was in a terrible state and I didn’t have time to actually do it. You’ve got a family, and all sorts of other things happened.”

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

Dealing with car dealers

One of those ‘things’ was using his motor trade experience to write a popular book called Dealing with Car Dealers, lifting the lid on the sales tactics used by dealers.

“Two years at BMW was enough,” he says. “All the people were pretty young, and really there wasn’t going to be much of a future in it. It was all very exciting but I could see in 10 years’ time if I’m still doing this I’d feel a bit of a failure really.”

It was also an unforgiving environment, and James had to learn fast.

“You had to grow up really fast and really understand how part exchanges worked,” he says. “From knowing nothing about that side of it you learned extremely quickly, because otherwise you wouldn’t get paid. They would sack you if you made a mistake on a part exchange – you’d be gone, because you’d lose money for them. It was brutal but it concentrated the mind wonderfully.”

He had always enjoyed writing and, after leaving BMW, sharpened his skills working in advertising copywriting, taking his dealer manuscript to Haynes Publishing.

“People never spoke about how you were sold to, so I wrote this book and Haynes said ‘yeah, all right, we’ll publish that’,” he says. “I was very, very lucky. That did quite well, it sold out very quickly, and that indirectly led to me becoming a freelance writer. ”It led to a used car column in CAR magazine, features for the Independent newspaper and a range of magazines, including Autocar.

The rise of Bangernomics

And then there was Bangernomics, a new name for an old concept that had fascinated James since childhood.

“I certainly didn’t come up with the concept,” he explains. “It was my dad telling me about a bloke he used to work with in the 1950s who would never spend more than £5 on a car.

“He bought Prefects and old stuff like that, and he would genuinely not put anything but petrol in it, not even oil, but he got about a year out of a car.

“It’s a terrible thing to do because when it stopped he just got out, hitched a lift or caught a bus, left it there by the road and bought another one.”

In 1989, James found himself without a car for a couple of days, and decided it would be cheaper to buy an old banger than use taxis, trains or buses to get to a Gloria Estefan concert.

He paid £80 for a Polski Fiat 125p. It was awful, but owning it made good copy, and Bangernomics made its print debut in a feature entitled ‘Better than Walking’ in Buying Cars magazine.

A book followed, and a legion of devotees.

As well as running and ditching dead cars, Bangernomics was about keeping old cars running on a shoestring. “You were around dads and grandads and uncles who would take the head off at a weekend to de-coke it,” he says. “You would read in Car Mechanics ‘de-coke your A30 head’ and people would. It’s so sad that we’ve completely lost that. That’s how most people used to run their cars.”

Mini the best banger

There are few cars more suitable for this form of Bangernomics than the Mini, according to James.

“They are the best bangers of all,” he says. “I think they are extremely reliable and they will still run even when they actually shouldn’t.

“I remember a time when the starter motor went on another Mini I owned and, because I was young and fit at the time, for a few weeks I just push-started it everywhere. It was only a few quid to pay for an exchange starter, but I couldn’t afford it.”

With the Cooper stuck in a lock up in Ruislip, gradually deteriorating, James bought two further Minis – one Cooper and one standard car.

“I bought them because I missed it, and I thought getting it into a decent state again will take me so long,” he says, cannibalising the good bits from the standard Mini to make a good Cooper.

“It’s something that you don’t do anymore, but you could still do in the 80s, and it was quicker and far cheaper to buy a Cooper in a terrible state and a half decent Mini and just swap bits over.”

The move to Norfolk in the 1990s was the nudge James needed to rescue his original Cooper from its locked-up misery.

“It was left untouched for too long, at least 10 years,” he says, bringing the car to the countryside on a trailer.

“It wasn’t great – you can’t quite believe how something disintegrates over time if you don’t use it. It was unbelievable, deep-seated rust.

Metro engine

“A friend who ran a Mini centre near Cambridge got me loads of parts and we made it run. I even had a sprayed red, exchange Metro A-plus series engine in it for a while because the original engine was seized solid, in a dreadful state.

“That ran every well, and I ran around on that for a few years.”

With the rust sorted and a working engine, James was finally using the Mini regularly, and would pick his daughter up from school, adding a roll cage for “a bit of protection if I rolled it into a field”.

Other non standard items on the car are a Moto Lita steering wheel and Cooper S reverse wheel rims, both of which were in situ when James bought the car back in ‘79.

There are also parts of his original £50 Mini on the Cooper.

“The boot lid is there, the bonnet is there, and a few other bits and pieces,” he says. “People go on about originality, but if you ever pay attention to originality anoraks you’d go mad – they’re just so boring.

“The point of the Mini, I’ve always thought, is it’s individual to you. If you want to paint it a different colour or put something on it, you do it. That’s what people used to do – in the ‘60s you bought Hot Car magazine, Car and Car Conversions.

“All the adverts at the back – it was brilliant. It was like, put a dash on so you had 23 dials, yeah, let’s do that. It was great.”

By 2010, rust had taken hold again and the Cooper was once more in need of serious work.

James “bit the bullet” and, this time, opted to pay someone else to rescue the car for a third time.

Rust and another restoration

“As I’ve got older I’ve been more reluctant to do it myself, whether it’s because I’m busy doing other things, but I would rather give it to someone else,” he says. “I didn’t have the time to do it, and I don’t think I had the skill to do it so I decided right, OK, we’ll get it done properly.”

The original, 998cc A-series engine was sent to a friend in the village, who used to work on Lotus engines, for a rebuild, while the bodywork was undertaken by the East Anglian Mini Centre in Ipswich.

“It gets shot-blasted, and the whole front’s disappeared,” says James. “Once you take it down to bare metal, there’s not much bare metal left.

“You think ‘that whole front was fine before’. And the floor…I’ve done that floor once and patched it several times. In order to do something properly so it’s as nice as it is now, you really have to take it right back to basics and rebuild it.”

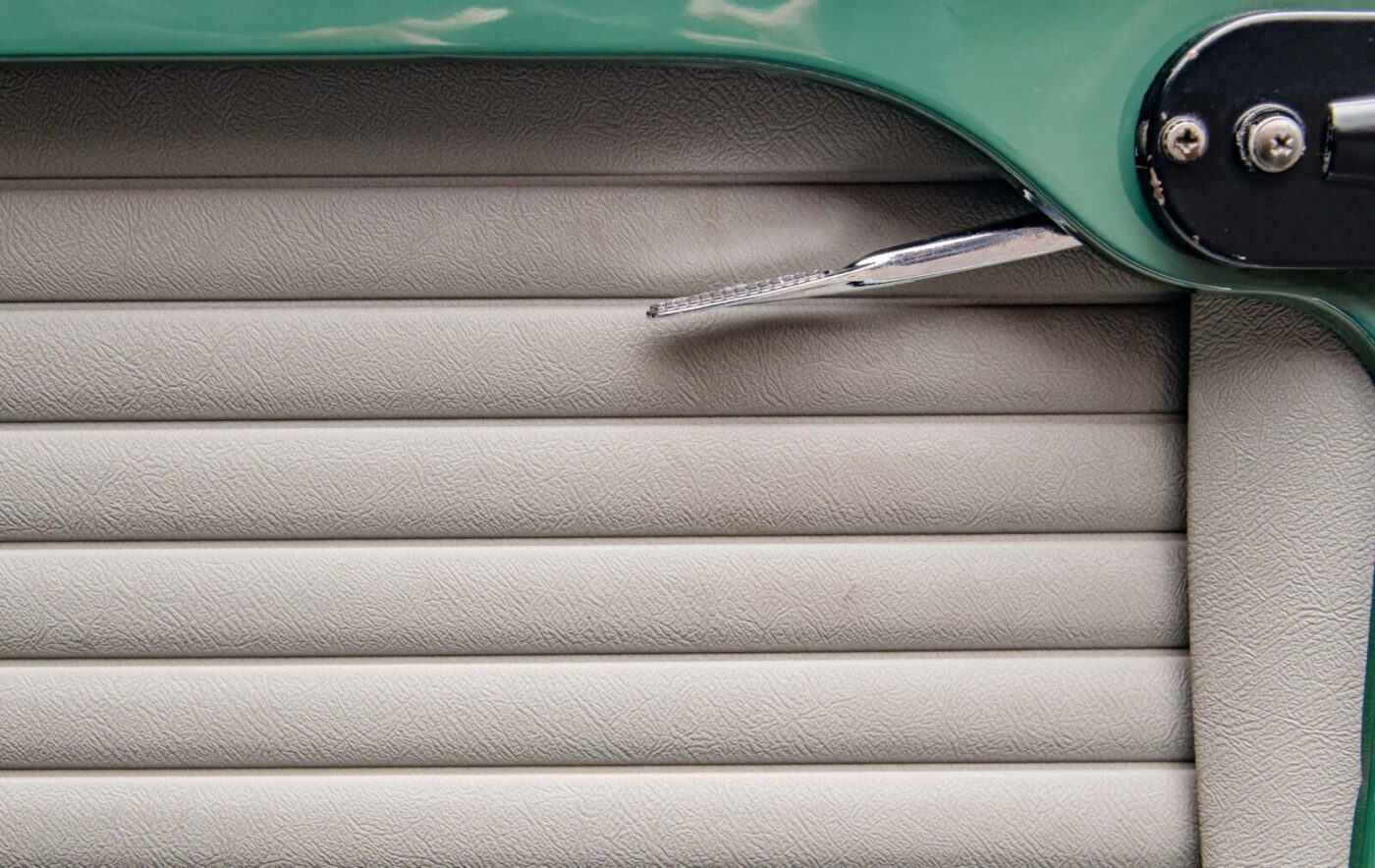

The original interior merely needed a bit of stitching up and a damn good clean, but the bodywork was away from Norfolk for three, expensive, years.

And that’s when James started to have second (and third, and fourth) thoughts about sinking so much money into the car.

“All I seemed to do was send money,” he says. “My wife said to me at the time, ‘do you just want to sell it?’ I did, I just wanted to sell it, I wasn’t very happy at all.

“It just didn’t seem the right thing to do. It just seemed ridiculous, and it went on forever. It was like the worst thing ever, talking to this bloke the whole time, approve this, approve that.

“I did think ‘I’ll just have it back and I’ll sort it out eventually’, but you know you won’t because you’ve got to earn a living, and have other things to do.”

After spending £20,000, James was understandably fussy about the quality of finish when he got the car back in 2013.

“It was an incredible amount just to do the body,” he says. “I did make them take the car back. I wasn’t very happy with it and I couldn’t in all conscience tell people to go and use them because there were so many faults with it.

“But, to his credit, he came back and redid it. When you get cars done by someone else it does pay to be really fussy.”

Was it worth it?

So when he first got behind the wheel again, did it all feel worth it?

“No, I was really pissed off about it,” he says, though taking some consolation from the knowledge that the car is now worth more than the £20,000 he spent.

While he may never fully come to terms with that outlay, James is once again besotted with his old friend, which remains in almost daily use.

“It’s adorable, of course it is, absolutely,” he says. “I think we all go through that love hate thing. “It was a bit too much bother, but I wouldn’t have it any other way and if I went down to one car then that would be the one car.

“The great thing about it is, I do use it. I’m not precious about it, I’ll go out in the rain. I live in a place that isn’t London, so not everybody wants to nick it, or take it off you, or smash your face in, so I’m very lucky about where I live. Everybody’s really nice here.”

As well as the sheer glee of flinging the Mini around mid-Norfolk’s twisty lanes, James enjoys bringing a little cheer into the lives of others.

“The brilliant thing about it is the reaction to it,” he says. “People are just so lovely, you get lots of people come over to you in the car park and say ‘I had one of those’.

“People just smile, people with small children will bring them over and everywhere it’s joy, you’re sort of spreading joy to people.

“I’m basically a miserable old bloke, so it’s a good way of me thinking I’m bringing joy to the world by driving this around.

“The saddest thing is that in the last few years I’ve seen maybe only one or two other Minis going the other way, where people go nuts because they see another Mini.”

To avoid another restoration, the most important thing is to keep using the car, which shares a garage with an early BMW 3-series and an imported, Bertone-styled Innocenti Mini.

“It’s incredible how something disintegrates over time, and it’s a lesson to us all,” he says. “You’ve got to use things, if you don’t use them they really do go to rack and ruin. That’s why I use my cars all the time.”

James describes himself as “loyal”, rather than sentimental, about his cars.

“I’m not overly sentimental, but if I like things I do keep them,” he adds. “This Mini is a good indication of that, I’ll keep it because I enjoy it.

“I know a lot of people who know a lot about cars, they will buy an iconic car and in six months time they’ll sell it, and I think ‘why have you done that’?

The perfect car

“For me the Mini is the perfect car, I can’t think of any other car. You can get four people in it, and get loads in it. It works as an everyday car.”

Will his daughter, now 23, handy with a spanner and a keen British Touring Car racing fan, one day keep the Mini in the family?

“It’s up to her, but she’s not extremely impressed,” says James. “I’d like to think it’s a small enough car to be stuffed away. Maybe sentiment will play a part.”

In the meantime, if you see an almond green Cooper with a white roof on Norfolk’s roads, give it a wave. It’s good for the soul of one “miserable old bloke”.