You’d expect a car costing just £7 and 10 shillings to be little more than an old banger and a heap of trouble, even at 1968 prices.

But for the equivalent of about £130 in today’s money – the going rate for an MoT failure – Robin Southward drove away in a car that had captivated him for years, a now-historic and rare Aston Martin DB1 since passed on to his son Allan.

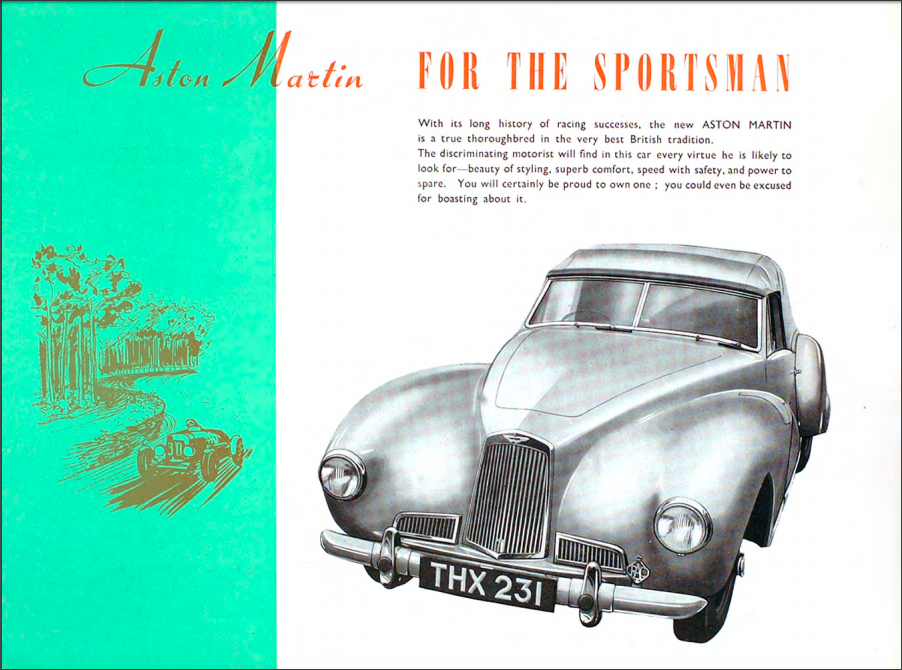

Launched in 1948 as the Aston Martin 2-litre Sports and later rechristened the DB1, it was the car that started the David Brown story, a gorgeous, flowing drophead that caught the eye of a teenage Robin on visits to family friends.

The car, one of only 15 made, was owned by the wife of Dr Campbell Golding, a friend of Robin’s father, who bought it new for a little over £2,300 in 1950.

Sitting in the drawing room of Robin’s Beckenham home, Allan – who took ownership of the Aston in 1999 and remembers tinkering with it as a young boy – tells how his father first fell in love with the car that will one day pass to his own son, Ethan.

“Dr Golding was a friend of my grandfather and, as luck would have it, dad would end up round at their house in St John’s Wood on a frequent basis and tended to admire the car,” he says.

“Dr Golding’s wife owned it from new and, occasionally, because all she did was drive it around London, it would not work particularly well. Their chauffeur would take it back down to the Aston factory at Feltham and they could never find anything wrong with it.

One day, dad offered to help

“It took a day to do this round trip and it would happen on a regular basis. She got a bit fed up with it, and then one day dad offered to help.”

Robin, now 80 and recovering from a hip replacement operation, joins us and takes up the story.

“I was 18 or 19 at the time, and I worked for Tecalemit at Feltham making lubrication equipment for garages. Next door to them was Aston Martin,” he says.

“I said if anything goes wrong again, I go down to Feltham anyway and perhaps I can drive it down there and bring it back afterwards to save your chauffeur the day.

“She said ‘if it’s not too much trouble’.”

It was anything but trouble.

“It was fantastic to have this car, driving down the Twickenham bypass, the only bit of dual carriageway around at the time,” says Robin.

Once again, the Aston engineers could find nothing wrong with the car because, says Allan, “all it needed was a good thrashing on an open road to clear it out and everything would be fine”.

So Robin volunteered to take the Aston out on a regular basis, to shake off the cobwebs and keep the Claude Hill engine running as it should.

“Once a month I’d ask ‘is the car going all right?’” he remembers. “She’d say ‘well, no, it needs something done about it, but I can’t ask you to do it all the time.’

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

It ran like a bird

“I was more than happy to do it. For a while I took the car and thrashed it down to Feltham and it ran like a bird. They could never find anything wrong with it – it just needed to be used.

“I always said to her if you ever want to get rid of it let me know and it will go to a good home.”

The years rolled past and, in 1968, Mrs Golding was ready to take Robin up on his offer.

“She stopped driving it when her two sons came to the right age to drive and, after driving it around for six months, they said to her ‘the car’s terrible, it’s falling apart’,” says Robin.

“It then sat in her garage for a couple of years amongst chickens.”

By then, the DB6 had been in production for three years, costing a shade under £5,000 new, and the DB1 was not generally considered anything special.

“She rang me up one day and said ‘I’m thinking of getting rid of my Aston Martin and I know you were interested’. I said ‘definitely, I would be’,” says Robin, who wasted no time in going round to look at the car.

“I asked her how much she wanted for it and she said ‘is £5 too much?’ I said ‘well, because you are on the same committee as my mother in St John’s Wood, I will pay you a little bit more.’ ‘How much more?’ I said ‘£7 and 10 shillings’.

“She said ‘that would be fine’. I told her I wouldn’t sell it, and have kept it ever since.”

Bargain of the century

And with that, Robin had picked up the bargain of the century – a new Mini at the time would cost about £600, and the only cars you could pick up for under £10 were unwanted pre-war motors or old bangers.

“They weren’t really sought after, only by oddities,” smiles Robin. “People weren’t expected to own and drive that sort of car. They thought we were odd.”

“Not many people knew about them,” adds Allan. “And that was the case until maybe 15 years ago and then prices just went through the roof.”

Even so, the drive home from the Golding’s house at Godalming in Surrey brought home to Robin that the car he had just bought for less than a week’s wages was far more than just an old used car – even if it had its flaws after two years off the road.

“I stopped at the motorway services near London Airport and someone came up to me, went to take a wad out of their inner pocket and said ‘I will give you £1,000 cash now’,” he says.

“I said ‘no, I think it’s probably worth a bit more than that’.”

No matter that the cover on the back wing had already come loose, landed in the middle of the A30 and been run over by a couple of cars – Robin had his Aston Martin and he wasn’t letting it go, even for an immediate huge profit and with a house to pay for with his new wife Davina.

“My father wasn’t happy,” he says. “He said I should have accepted the money and said ‘don’t come to me for any money from now on’.

“The first thing my father and my mother used to say every time we saw them was ‘have you sold your car yet?’ I would say ‘no, I’m not selling it.’ They’d say ‘you should get rid of it, you can’t keep on with this old thing.’

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

“One of those things I wanted to keep”

“Some things you need to keep and some things you get rid of, and this was one of those things I wanted to keep.”

At the time, the car was gold, resprayed when new from its original metallic blue at the request of Mrs Golding, but Robin soon changed it back to light blue.

Robin used the car regularly for many years, and when three children came along they would cram into the small back seat for family outings, come rain or shine.

“We would be out all the time,” says Allan, 43, an IT director for a major UK bank. “We’d drive around at weekends and go to Aston Owners Club meetings.

“It was just what we did as children – no seat belts, crawling around in the back, the wind in your hair. We would drive along even in pouring rain; the roof would be up and my sister and I would be in the back with a box of tissues stuffing them down the side so we would not get wet.”

By the early 1980s, the first of the David Brown Astons was starting to feel its age and Robin, with young Allan’s “help”, began stripping the car for a major rebuild.

“Whenever you went anywhere in the car you always knew you might not get there!” says Robin.

“Everything always needed tweaking. Wherever you went something used to happen. I remember going down Corkscrew Hill and I could not get round the corner at the bottom; the steering box had broken in two and the front wheels went in different directions.”

Once father and son started to take the car apart, they discovered that many of the screws and tubes beneath the bodywork had simply rotted away.

“I remember distinctly having a screwdriver in my hand and being left to take bits of the car off, which I’m sure I was breaking as I was doing so,” says Allan.

“Big part of my childhood”

“That was a big part of my childhood. Dad was an engineer by trade, and on a Sunday he’d be out there all day working on the car in the drive. My mother would be angry because he would not come in for lunch or dinner, he’d cover it over with a tarpaulin and come back and carry on the next week.

“The chassis was sent away to be blasted and zinc sprayed and I remember one day when it came back on a lorry with three or four delivery guys.”

That was in 1983, but it was to be another 30 years before the project was finished, as Robin became distracted by other projects, not least the Maserati-engined Citroen SM, three examples of which share garage and driveway space with the Aston.

“It’s the be all and end all of cars”, says Robin.

The half-finished Aston sat in the garage for years, despite some abortive attempts at getting it back to its former glory.

“All the bits sat in boxes,” says Allan. “We tried to get people to do different bits – the body went off to be painted but he never did it. It sat in the back of his paintshop, and five years went by, literally!

“It got covered in dust, dirty, knocked and scraped. But at least it was garaged.”

By the late 1990s, Allan was old enough to take matters into his own hands and persuaded his father to let him loose on the car, and transfer its ownership.

“I’ve got a great interest in mechanical things, even though my day job is in software, and it was just ‘let’s start putting it back together again’,” he says, with the car finally resprayed back to blue somewhere along the way.

“Dad always said ‘no, no, I will do it’, but eventually I managed to prise it from his still warm hands.

“We met people along the way who are really good with those cars, just magicians. They’re not the kind of people with dollar signs in their eyes, they’re high quality people who care about what they do.

“Three or four years ago we finally got the engine running again and we’ve incrementally built up reliability and now it’s running really well.”

Allan’s mission now is to make these important cars, only nine of which are thought to survive, known to a wider audience. And it’s set to be on display at the Silverstone Classic between July 20-22.

“Many people don’t even know these cars exist,” he says. “They know of the DB5 because of the James Bond films, but they don’t know the earlier cars so I’ve been trying to get it seen and show people these cars exist.”

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

The first David Brown car

David Brown, a gearbox and tractor manufacturer, bought Aston Martin in 1947, answering a small ad in The Times late the previous year offering a sports car company for sale for £20,000.

At the time, the company was struggling to get back into car production after the war, with finance needed to continue development of a successor to the wartime “Atom” prototype, developed by Aston’s chief engineer Claude Hill and featuring his new 2-litre engine.

“David Brown had seen and driven the Atom, and was so impressed he decided to buy Aston Martin,” says Allan.

With Brown providing financial security, work progressed on the new car, with a special-bodied version winning the 1948 Spa 24-hour race in the hands of drivers St. John Horsfall and Leslie Johnson.

Soon after buying Aston Martin, Brown also bought Lagonda, whose designer Frank Feeley penned an all-new body for the Spa-winning car ready for the 1948 London Motor Show.

This was the 2-litre Sports, renamed the DB1 on the DB2’s introduction in 1950.

“This car combines the Aston Martin engine and chassis by Claude Hill, with Frank Feeley designed bodywork and a David Brown gearbox,” says Allan.

“It brought together all of those skills and products into what became the first David Brown car.”

The 90bhp engine could propel the lightweight car, the first to bear the distinctive 3-part grille, to a theoretical top speed of 93mph.

Including the Spa prototype, only 12 examples were originally made, and Allan’s – chassis number 13 – only exists thanks to the Hon JCC Cavendish (later Lord Chesham), who specifically requested a soft top when the DB2 only came with a hardtop.

“He was told that they would build him one if he could find three other buyers,” says Allan. “And that’s the only reason this car was built.”

Over the years, Robin turned down several offers for the car and, having finally got it back on the road for the first time since 1981, Allan is in no hurry to cash in on his father’s canny investment.

“This is my father’s legacy”

“I’m never going to be able to have something like this ever again,” he says. “This is my father’s legacy living on through the generations. He’s rebuilt the car – underneath there’s a lot of wood he shaped himself. He’s built that from scratch.

“That’s why I wanted to get it finished, to get it done, and one day I will hand it on to my son, Ethan, who is 12.”

As well as the joy of driving such a beautiful and rare car worth more than £1million, it also opens doors to a world most people never experience.

“Drive down the road and people wave at you and they smile,” says Allan. “That’s the best thing really. Get back in a daily car and you are invisible again.

“Because of the car, last summer I was invited to the Goodwood Festival of Speed on the lawn.

“The car next to me was a DB4 Zagato worth £10m. I was invited to the ball, sitting with people worth hundreds of millions, and on the next-but-one table were Bernie Ecclestone and Christian Horner.

“It was very strange, I almost felt like an imposter, and it’s only because the car’s so very special that I have these experiences – experiences I would not normally have.”

Both father and son have lived the Aston Martin dream, and all for an initial outlay of just £7 and 10 shillings.

Classic car lovers can get up close and personal with the DB1 when it goes on display at the Silverstone Classic on July 20-22. Adrian Flux is proud to be the event’s Official Vehicle Insurance Partner.

Photographs by Simon Finlay Photography