It was January 1971, and teenager Chris Marsden was sitting in his kitchen in Jersey, waiting to go to school and listening to the radio.

His ears pricked when it was announced that a car he’d never heard of, a Renault-powered Alpine, had just won the Monte Carlo Rally.

Already intrigued by the rear-engined Renault Dauphine his father had turned up in one day, he resolved to find out more about the Alpine.

“Soon after, a magazine came out and there was a photograph on the front page and an article inside about this Alpine Renault, and I just fell in love with it the moment I saw this thing,” he remembers. “I thought ‘God, that looks the business’.”

Chris and a school friend then boarded an old DC-3 plane for a short trip to Saint-Malo, where Renault was showcasing its latest models including the new R15 and R17 ranges.

“They had a display of all their cars on the seafront by the casino, and something told us if we hung around there one of these Alpines may turn up and, bloody hell, it did,” he says. “That was the first time I saw one in the flesh, and it was one of those light bulb moments. I decided then and there ‘I don’t care how long it takes, I’m having one of those’.”

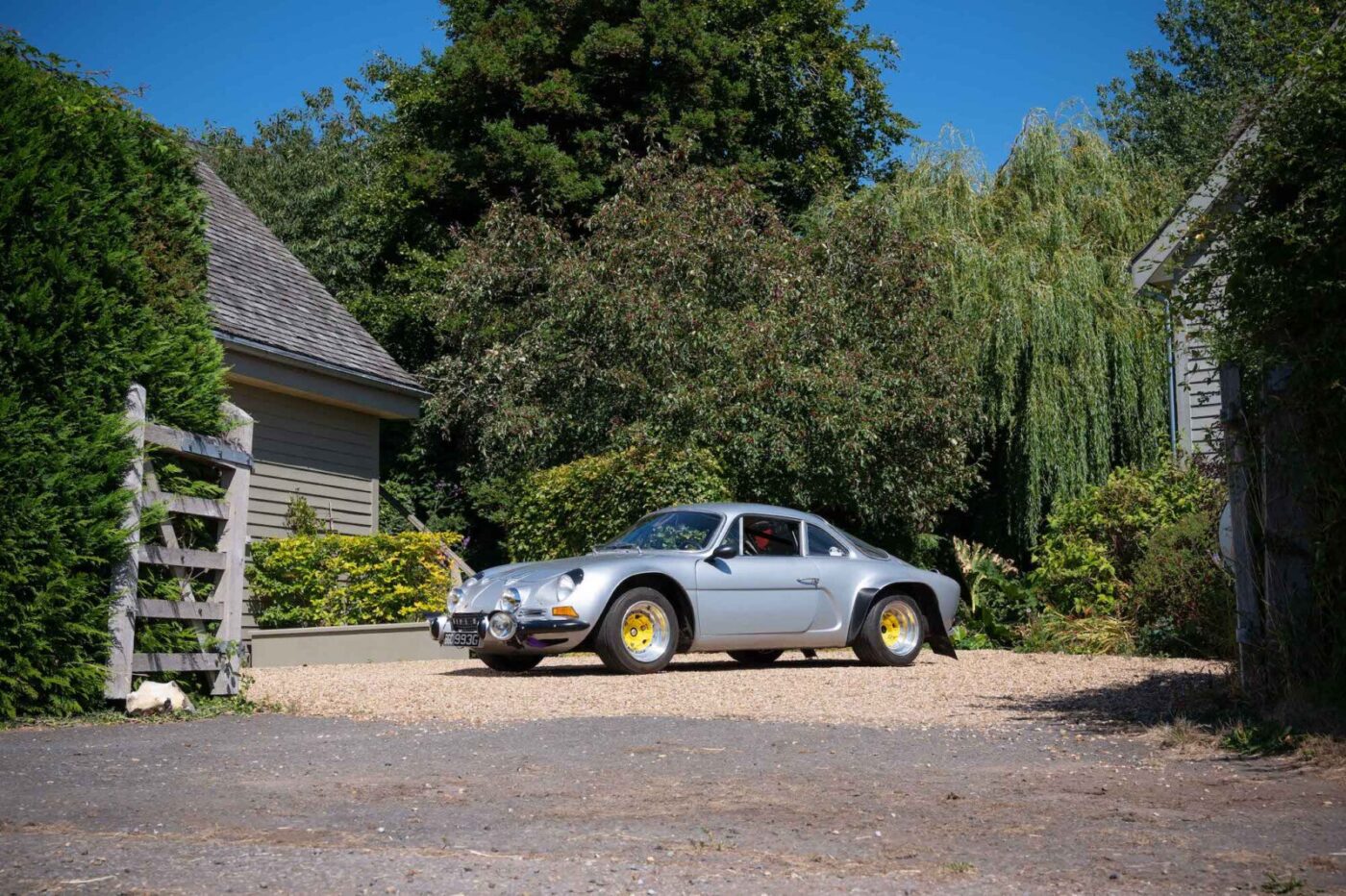

It took a little over 20 years, Chris buying the stunning 1968-built car you see here in 1992 for £10,000 as a non runner.

But that was only the start of a long and difficult restoration, including work on a bent chassis, a rear end body swap, an engine change, upgraded brakes and a mostly new interior.

The Alpine wasn’t on the road at all until some time in 2020, and it wasn’t until the replacement engine was fitted a year later that Chris was finally happy with the car’s performance.

“To get it to where it is now has been a very long, involved trip,” he says. “It was a dream, and it’s a dream I’ve made come true. There’s a lot of love gone into that car, and I love it to bits – but although it’s small, it’s been a real sod to restore.

“Thanks go to my wife Lesley, my beautiful assistant, who has had to put up with me swearing at it when things didn’t go so well.”

Chris, now 70, has come a long way from his first car, a 1956 split screen Morris Minor bought for £5 from a nurse in St Helier.

“That was pretty cheap even then,” he says, “the only problem was that it didn’t have any hydraulic brakes, so my dad and I actually drove it home on the handbrake, something you wouldn’t dream of doing now.

“So the first job I got to learn about with car mechanics was how to fix brakes – new master cylinder, new brake pipes, bleed the brakes…

“I hadn’t even passed my test then, but we lived next to where they were building some new houses in Jersey so, after school every day, I used to get in the car and drive round the site after the builders had packed up for the day, learning how to change gear etc. I was very fortunate because motoring in the Channel Islands was very cheap back then, £8 a year road tax, 20p a gallon for fuel. I could afford, in the sixth form at school, to run a car.”

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

Then came the Renault Dauphine, which first piqued Chris’s interest in French cars, and on which the Alpine A108 was loosely based.

“My dad turned up with this strange French car with the engine in the back, leaving me wondering what that was all about,” he says. “I got used to its idiosyncrasies, having a gear stick you could stir porridge with in any gear owing to the distance from the lever to the gearbox on the rear axle, and I recall having some difficulties with the cooling system which had to be very exact.”

For many years, owning the object of his desire was something of a pipe dream for Chris, as rising prices outstripped his ability to pay.

The A110’s desirability only grew after the car won the first World Rally Championship in 1973, including another win at Monte Carlo, before the Lancia Stratos appeared to steal its crown.

It was based on Renault 8 mechanicals, with power units ranging from a 956cc unit at launch in 1963, up to the 1647cc Renault 16TX unit that now resides in Chris’s car.

Originally built by the independent Alpine company in Dieppe, subsumed by Renault in 1974 during the oil crisis, production ran alongside the Alpine A310 between 1971 and 1977.

And it’s the A310 that proved the gateway for Chris to realise his original Alpine dream.

“In 1986, I was driving up the M1 one day from Sheffield, stopped at the services, went into the shop, and I was browsing Autosport magazine when I saw an advert for the Alpine A310V6 for sale,” he remembers. “The contact phone number was in Manchester, so I thought ‘I’m at least going to have a look at this thing’.

“Following a second visit, with a pair of overalls, the owner let me take the car up the East Lancs Road, where I could spend some time with it and give it a good look over.

“It was only three years old at the time, and I ended up buying the car from the chap in a pub somewhere off the M61. It’s been a reliable car, but now needs some restoration itself, which I’ve begun.”

Chris describes the 1983 A310, powered by a 2664cc V6 engine, as a “good touring car” that he’s driven to France and Scotland.

The car had a major role to play in Chris finding the A110 in London.

“The windscreen on the A310 cracked, so I had to get a new one,” he says. “I knew a chap in London who dealt in these cars, so I rang him up and he said ‘yeah, I’ve got a windscreen in stock, but how am I going to get it to you’, as he wasn’t prepared to have it couriered?’

“I said I’d come and get it, so along with my two lads, we jumped in the car, drove down to the Crystal Palace area and that car (the A110) was in his workshop. I got talking to him and he said ‘oh yeah, it’s for sale’.

“I just thought ‘this is my opportunity, if I don’t buy this car I’m never going to get one’, because even then there’s no way I could have afforded a restored one. The only way I was going to own one was to find one that required restoring. Plus, it’s something I’d wanted to do, as that way you get to know every last nut and bolt.

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

“I know £10,000 doesn’t sound a lot now, but it was a lot then for a car that didn’t even run and was missing more parts than it had. Sometimes you’ve just got to recognise the opportunity and grab it.”

Grab it he did, putting the then white car on a trailer and getting it back to West Yorkshire, where the family was living.

Chris was 40 at the time, and little did he know he would be nearly 70 by the time the Alpine was ready for the road.

The car followed Chris through several house moves, including to their current home in North Norfolk, which he and his wife Lesley had built from scratch in the time it took to complete the work on the Alpine.

Along the way, the car was rebuilt from the ground up.

“It turned out that there was some accident damage to the chassis, so the body came off,” he says.

“It was hung on ropes in the garage, and I found a company called Naylor Brothers, in Bradford, who made replica MGs. They repaired the chassis, and I got that back, got it rust-proofed and repainted it, and then spent a lot of time looking for parts.”

As for the body, Chris set about removing the paint to get it down to the bare fibreglass.

“It had nine colours on it, and the metallic grey seen here is its original colour from the factory, and was right at the bottom,” he says. “We subsequently found out it had been a circuit racing car, and I think somebody had just sprayed over it every year without taking the previous colours off.

“When I took all the paint off it the roof looked like a moon crater – it had deep scores in it from the factory that had been filled.

“I contacted a guy in Sussex who restores Lotuses, particularly the bodywork, and I sent him some pictures. He’d written a book on restoring fibreglass bodywork and he replied saying ‘like the good book says, grind it all off’. It takes a bit of a leap of faith to take a grinder to your car, your heart’s in your mouth.”

It wasn’t the only time Chris’s heart was in his mouth.

“It needed a new rear end, because it had been converted to have a removable panel to simplify the removal of the engine/gearbox assembly. Through one of the French magazines, I managed to track down a complete rear end in a barn find in Brittany,” he says. “We went across and brought it back and grafted it on. If anyone ever says, where was the turning point in the restoration, that’s it – when you reach the point of cutting the back end off, you think ‘Christ, what have I done?’

“The Group 4 arches were on it when I bought it, but somebody had pop-riveted them on and slapped fibreglass over the top, which isn’t the right way to do it. That all had to come off and be put on correctly.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“That’s where I came across Scott and Ronni Groves at Corvette Kingdom. I thought I’d got to the point where it needed painting, and I got in touch with Scott because I figured that as he dealt with Corvettes, which are also fibreglass, that he would know someone who knew how to paint fibreglass.

“I also reasoned that being in North Norfolk, where there is an industry building and painting fibreglass boats, I was in a place where there was plenty of expertise, which turned out to be correct.

“The car ended up staying with Scott in his workshop for a couple of years, where the wings were correctly fitted. After it was painted, he was kind enough to let me go in on a Friday to re-fit parts to the car.

“His wife, Ronni, who is also an ace welder, fitted the interior for me and did a great job, so many thanks need to go to them for their help.”

Others helped out along the way, including good friend Graham Austin, who provided both encouragement and bits of welding here and there; Chris’s son Dan, who at one point got the brackets for the spotlights made by his metalwork teacher at college, copied from originals; John Henderson and Ted Franklin from the Renault Owners Club, who provided parts; and Steve Swan in Perth, Scotland, who rebuilt the gearbox.

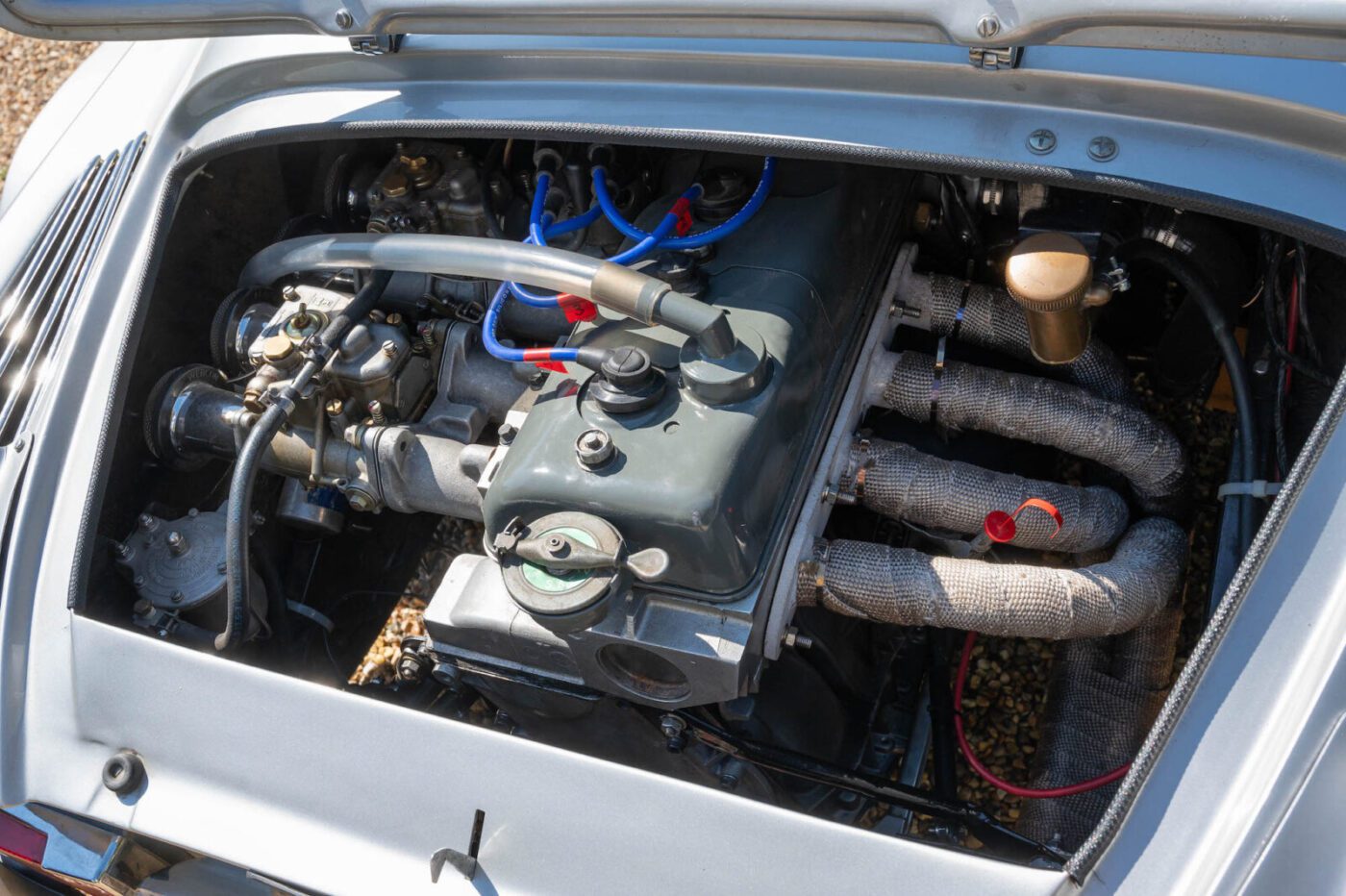

So what of that all-important engine, originally a 1565cc unit from a Renault 16TS?

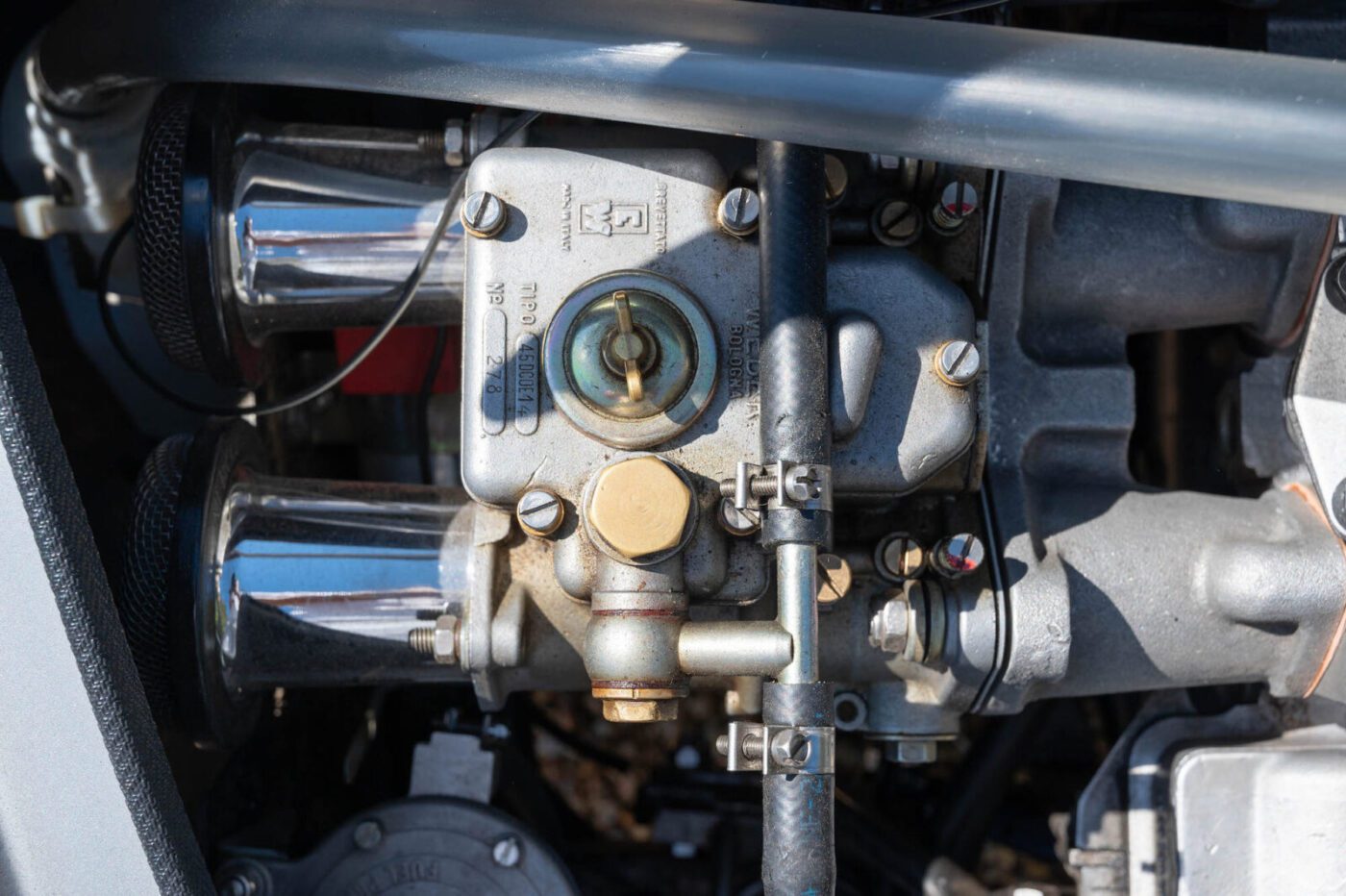

“I’d no idea if it ran, and I’d no way of getting it to run,” says Chris. “It had a brand new cylinder head on it, and the car had, interestingly, been re-wired when I bought it and which I did not disturb in any way. The original Weber DCOE45 carburettors were still there but they looked like they should be in the bin.

“When we first ran its original engine you couldn’t drive it under 3,000 revs, because it had such a wild camshaft. Once you got over 3,000 revs on the road – woom – but you couldn’t drive it on the road like that, it was just impossible.

“That’s when I got hold of Salv Sacco from the West Midlands. Salv is the ‘go to’ man for these engines, and I owe him many thanks. My son and I took the original engine over to him, and I caught the train back home from Wolverhampton. I was at the station and he rang about 10 minutes after I’d left him and said ‘you do know your pistons are in 180 degrees the wrong way round?’ Now, I’d had the cylinder head done to run on unleaded previously, but I hadn’t got that far down. The valves were just starting to kiss the pistons, but fortunately hadn’t done any damage.

“Salv put it back together with new valve gear and a reprofiled camshaft, but didn’t do anything with the block.”

Nonetheless, a replacement engine was secured from a Renault 16TX, which Salv re-built and I installed over winter 2021, complete with the rebuilt Webers.

“I’d found a guy down in Chelmsford who refurbished them and made an absolutely wonderful job of it,” says Chris. “They look brand new.”

Other changes include the clutch, which was originally a cable-operated number that Chris spent months working on but couldn’t get to operate correctly.

“You had to have a really strong left leg to make it work, it was that heavy,” he says. “At one point I found someone near Newmarket who rebuilds clutches, and he rebuilt it for me but it made no difference. Salv subsequently fitted a clutch from a Renault 18 Turbo when he rebuilt the engine, which is much lighter.

“However, what struck me one day was that the A310 has a hydraulic clutch, and I thought ‘hang on a minute’. The last A110s they made had hydraulic clutches, so it’s got to be the way to go, given the distance from the clutch pedal to what is, after all, a rear, not mid-engined car. So I bought all the master cylinder, slave cylinder, and lines that they fitted on the later cars and fitted them and, do you know, it’s like chalk and cheese. It might not be total originality, but it doesn’t half make it easier to drive.”

As for stopping power, Chris has replaced the original ‘petite’ brakes with the big brakes used on the 1600S, the most desirable of the A110s.

“The front calipers and discs are from the Renault 16, and the rear callipers are off, believe it or not, the Chrysler 180 and Matra Bagheera” he says. “The 1600S model is the one everybody wants, and it’s the most expensive because it’s the one the works team used to rally. These cars are so small you tend to wear them like a pair of trousers rather than get in and out. There’s a definite knack to entering and exiting.

“This car is a very early 1600, in fact it was number nine off the production line, but is probably up to 1600S spec now.”

Although Chris drove the car with its original engine, which is in the garage along with the off-the-road A310 and his wife’s classic Fiat 500, it’s only since the new unit has been installed last winter that he’s been happy with the Alpine.

“It goes well, but it could go better,” he says. “It’s still not entirely there yet. I had it tuned locally, and it had some of those socks over the air intakes on the carbs. The tuner removed those and immediately got another 23bhp, so they went in the bin.

“I’ve now got some trumpets on with gauze ends, but Salv, when he came over to tune it a few months ago, said that even they were preventing the engine realising its true power. The bigger the air filter, the better, and it should be in the rear wing fed by one of the two air scoops.

“I’m still looking for an original air filter, which seem to be like the proverbial rocking horse poo.”

Minor quibbles aside, Chris is finally enjoying driving the car he dreamed about for so long, and took it back to France for the 2022 Le Mans Classic, albeit on a trailer.

“It’s great to drive, though I’ve never pushed it hard yet,” he says. “We trailered it to Le Mans and then drove it to the circuit. It’s not a touring car, more point and squirt, and with two up there’s hardly room for your lunch, never mind luggage. It was an opportunity to drive it in France, as a French car. To me, driving over there is a pleasure compared to the UK. You get on some of the main roads in France, look in the mirror and there’s no one behind, or in front.

“We took it to Chartres-sur-le-Loir, where the drivers who raced at Le Mans back in the day used to stay. It’s like a shrine, everybody drives there and has their car photographed in front of the Hotel de France.”

Having spent so much time and money getting the car from non-runner to mint condition, Chris is determined to make the most of it.

“After all that effort, you want to get some use out of it,” he says, “and I don’t believe in selling members of the family, and that’s what it feels like.”