Barry Pendleton’s career in the offshore industry took him from south Wales in the west to Britain’s most easterly point in Lowestoft, via stints in the Scottish Highlands, the Midlands and the North East.

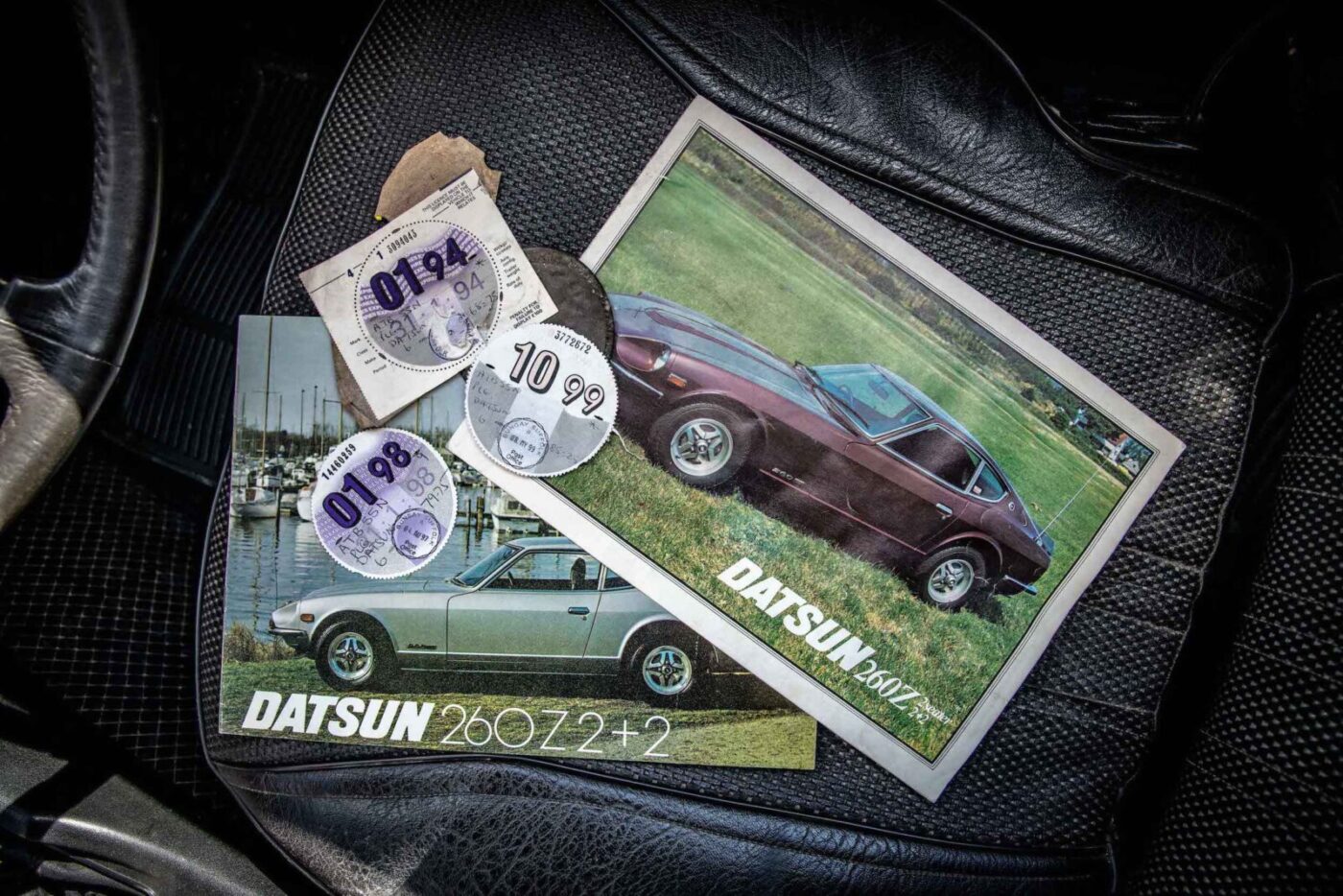

But wherever his work took him, one thing always came with him – his stunning silver Datsun 260Z bought for £3,500 in 1976.

More than four decades, two resprays and plenty of welding later, the Datsun remains Barry’s pride and joy, retirement giving him more time to fight the ongoing battle with corrosion.

“If I don’t keep on top of it, rust will kill it,” he says, at his home between Norwich and Lowestoft. “Eventually it would fall to dust. Rust is the biggest killer offshore, and it’s the same with the car.”

“Impractical” motor

Apart from one or two tiny bubbles, right now the car looks in exceptional nick in the spring sunshine, and Barry thinks back to what made him – as a 26-year-old father-of-two – buy such an “impractical” motor.

“I just saw one on the road and thought ‘what was that car? I’ve got to have it’,” he says. “There was one on the M6 as I was going back and forth with Jackie, a friend and colleague of mine, from Wales to Scotland.

“We stopped at a garage where the guy was filling up with petrol. Jackie and I went over and spoke to him, asked him his opinion, and he gave us some good feedback.

“It was the look of the car that attracted me to it. I just thought ‘my goodness that looks a nice car, a real head turner’. And it’s still a head turner now.”

With its long bonnet, sharply sloping nose and bulging, chopped-off rear end, the Datsun 260Z was the Japanese-born love child of the Jaguar E-Type and Ferrari GTO.

When it was launched as the 240Z in 1969, it caused quite a stir – here was a Japanese car to get the pulse racing, its modern looks light years ahead of British competitors like the MGB GT.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

The car for football legends

Its sharp lines prompted sportsmen to head to the Datsun showrooms, including footballers Kevin Keegan, Peter Shilton and Johan Cruyff, and Welsh rugby legend Barry John.

Barry wasn’t quite in that financial league, but having served a five-year engineering apprenticeship at a shipbuilding yard at Birkenhead, he got a job on an oil refinery at Cardiff as the North Sea oil industry was beginning to boom in the 1970s.

“There was good money in North Sea oil so, for the first time, I had expendable income,” he says.

Having first owned a Mini – scrapped for £50 – and then a Mini van, Barry’s first “decent car” once he had a bit of money to spend was a mark I Ford Granada Consul 2.5-litre automatic.

“It was a nice, comfy car, and it would really go,” says Barry. But then came that fateful moment on the M6, and the big, practical, family Ford’s days were numbered.

Luckily for Barry, with boys aged five and two, the Datsun was offered as a 2+2 as well as a two-seater, and he set about hunting down a good one.

After test-driving a few, including the one previously owned by Barry John, Barry headed to a dealer in Cardiff who had two for sale.

“I tried both of them out and this one was the better one,” he says, trading in the Consul in a deal with £3,500, a tidy sum back in 1976.

According to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, that’s nearly £25,000 in today’s money, and Barry points out that he could have bought a house for the money at the time.

“My first house in Wales was a new semi-detached and cost £4,500, not much more than the car,” he says.

Smiles and enjoyment

“Should I have bought another house instead of the Datsun? Yes, probably, but the Datsun has brought more smiles and enjoyment to my life than bricks and mortar.”

It was money well spent to Barry, who immediately fell for the car’s hairy-chested appeal and 2.6-litre, straight six engine that pushed out 150bhp.

“I was probably very impractical, but I just felt good in the car,” he says. “And the performance was awesome at the time.

“Unlike the Granada, there was no power steering and it did feel heavy. My power steering was to put a couple of extra psi in the front tyres!

“It was a very different drive, a very low drive. The bonnet’s so long, you can’t see the end of it from the driver’s seat.”

When he bought the car, Barry was living in Cardiff but working on oil rig construction at Kishorn in the Scottish Highlands, on a rotation of four weeks on and one week off, before eventually moving to Scotland full time.

There were family trips around Scotland and to the Isle of Skye, the cramped back seats adequate for the boys, Gareth and Lee, in those days.

Although largely reliable, wear and tear takes its toll on even the most robust of cars, and when the exhaust blew Barry asked a local garage to order him a new one from Inverness.

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

Exhaust conundrum

“I took it into the company workshop, ripped off the old exhaust from front to back, got the brand new exhaust and went underneath the car,” he says.

“It was about 10 inches too short! It was one of those moments – what have I done wrong? I kept thinking I could do a Paul Daniels and make it grow.

“It turned out it was for a 240Z two-seater, which was about 10 inches shorter. That was a funny drive home, about five or six miles from work to home with no exhaust at all. What a noise that made! It was late at night in the wilds of Scotland so I don’t think I upset too many people.”

With the correct exhaust fitted, the Datsun remained Barry’s daily driver for at least 10 years, but not without the odd incident and accident along the way – sometimes for unconventional reasons.

“In Scotland one time I very nearly lost it,” says Barry, his attention diverted by an eagle – or maybe a buzzard – perched in a tree.

Majestic creature

“There was about an inch of snow on the road, and I saw this majestic creature sitting in a tree. I thought ‘I’ll have a look at that’, put the brakes on and the back end went.

“I managed the catch it, but it was very heavy at the front and light on the back. You had to be very careful!”

Barry wasn’t quite so lucky on another outing in the snow: “The boys were crazing me to take them to school in the snow, I lost it and hit a woman’s car – she turned out to be a mum of some kids at the school”.

Another time, a youngster in a small Ford smashed into the Datsun’s rear end near the Bristol Channel.

“I could see him in my mirror looking out at the Channel, and he went straight into the back of me,” says Barry. “His car totally disintegrated, but I was able to drive home.”

Apart from the corroded exhaust, the only mechanical mishap was a blown head gasket when his wife was driving from Scotland to Wales, a rescue service coming to her aid.

Eventually, with the boys growing, Barry’s nagging doubt about the Datsun’s suitability as a family car led him to the local dealer for the one and only time he’s seriously considered selling the 260Z.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

Not a family car

“The kids would argue as to who sat on the tunnel between the gearbox and the exhaust, which gave a view through the front seats,” he says. “That’s when I knew it was not a family car.

“I’ve never advertised it, but they were growing a bit older and I thought ‘this is not practical for them’.

“I took it into a Datsun garage where they had a Datsun SSS, which was a bit bigger in the back. I asked the guy ‘how much for my car?’ He said ‘no, we won’t touch a 260Z’.

“They thought it was a specialist car, even though it was a Datsun. That’s the one and only time I’ve thought about getting rid of it.”

Instead, Barry kept the Datsun and bought a Saab 99 Turbo as well.

“That took over as the main car and the Datsun was sidelined,” says Barry. “I just could not get rid of it – I thought ‘this is such a nice looking car, I’ve got to keep it’.

“I’m fortunate that I always earned decent money, so it’s never been a necessity to sell. If something went wrong, I always had the money to repair it.

“Once I got the Saab, the Datsun was laid up and I didn’t even start the engine for five or six years.”

After moving to Norfolk, near his work in Lowestoft, building offshore accommodation modules, the 260 remained mothballed until the late 1980s.

Stopping the rot

“I got some money together and decided to have it done,” says Barry, who had spotted signs of corrosion and decided to, literally, stop the rot with a bare metal respray.

“The garage took the wings off and I got a phone call: ‘Barry, you’d better come and have a look at this, the inner wings have completely rotted through.’

“They were completely shot, and they were known for that. If I’d left it, it would have just fallen to bits. It would have just been scrap.”

With the inner wings replaced and the car back together with shiny new paintwork, it was used as Barry’s “toy”.

“In the offshore industry a lot of the guys had toys,” he says. “Because they had expendable income, they had fancy cars – Porsches and Daimlers etc.”

Over the years, the Datsun was given a few small upgrades, like a stainless steel exhaust, a set of alloys, and USA-spec rear bumper over-riders.

“I put the alloys on because I kept losing hubcaps and they were so expensive to buy at the time,” he says. “They’d just ping off and were proving very difficult to replace. If tie-wraps had been invented in the 1970s I’d probably never have changed them.

“I only put the over-riders on because I could not find any suitable rubber plugs to fit the ones missing from the bumper.”

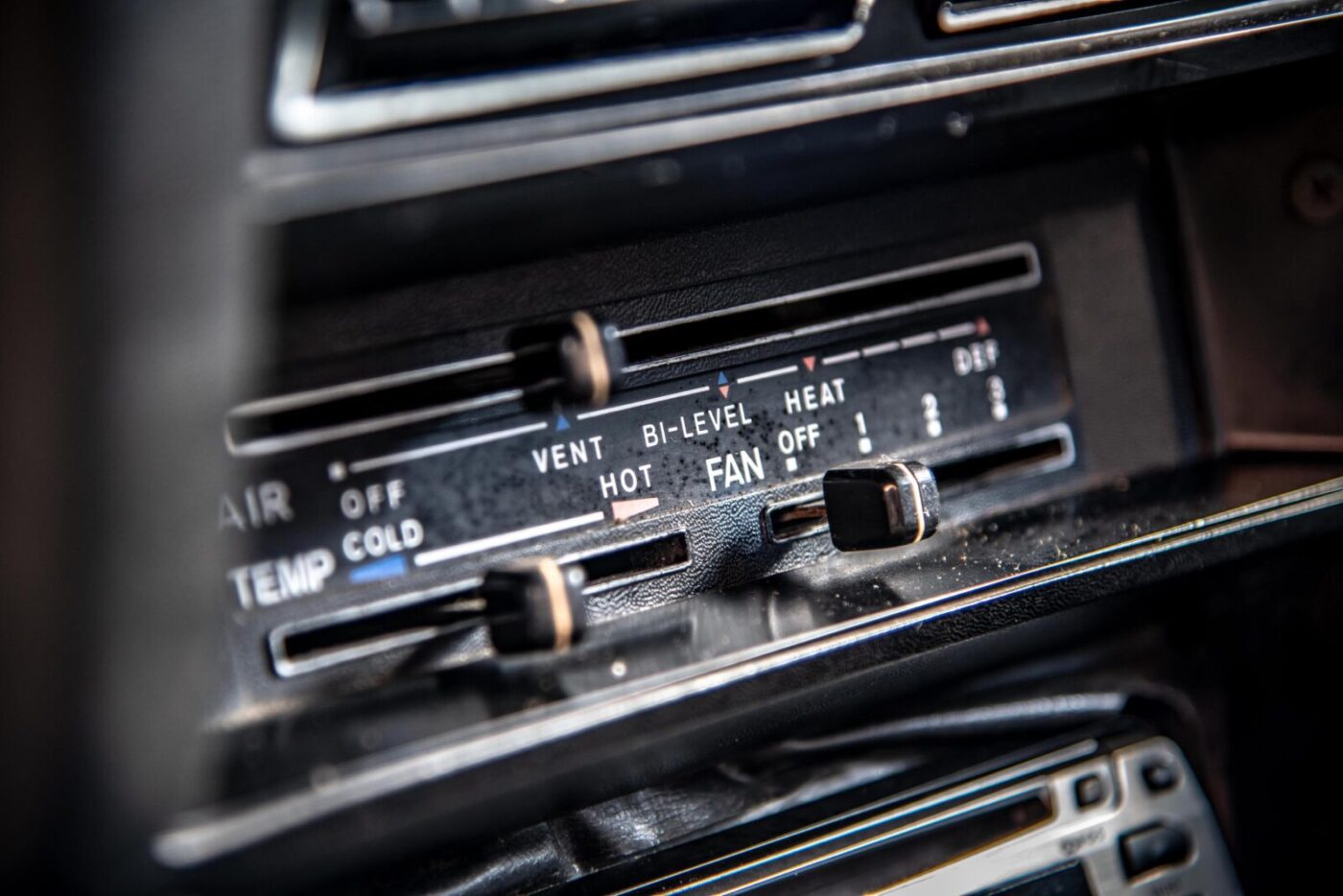

The original eight-track tape player has also been replaced by a more modern CD player.

Stripped down and overhauled

The engine, which has now covered 107,000 miles and requires an additive to run on unleaded petrol, was stripped down and overhauled about 20 years ago, and a second respray – and more complete restoration – was needed within the last 10 years.

“The underneath was the worst – it had started to rust,” says Barry. “Then, about four years ago I pulled out the back seat to get it recovered because the upholstery was shot, and there was a big hole the size of a football.”

Somewhere along the way, Barry bought a newer, faster iteration of the Z-car, a Nissan 350Z, but when he retired in 2015, a choice had to be made.

“I thought ‘right, I can’t really warrant having a 350 and a 260’,” he says. “I sold the 350 because I’m attached to the 260 – it just makes me feel good driving it and it still turns heads.

“I’ve actually been flagged down in Beccles by a guy flashing his lights behind me in a traffic jam. I thought ‘what’s wrong with him? What have I done?’ The next thing he’s banging on the window and saying ‘nice car, nice car. How long have you had it?’”

The answer is 43 years, and counting, and Barry, now 69, already has a plan up his sleeve for the day he can no longer drive the Datsun, one of only 28 licensed for the road in the UK at the time of writing.

I won’t be selling it

“I’ve thought about the future, and I won’t be selling it,” he says. “If I gave it to either of my sons I think they would just sell it. It probably doesn’t hold a great deal of sentiment to them. They do like it, and they send me photos if they see one on the road, but whether they’d keep it, I don’t know.

“I will eventually get them round a table and decide what they want to do with it, but if they don’t want to keep it then there’s a motor museum at Caister and I will probably ask them if they want it when I’m too old to drive it.”

The only thing that would change Barry’s mind is a major repair, with spares becoming harder to find and increasingly costly.

“Spares are becoming an issue now,” he says. “I need seals for the doors but they’re very difficult to get hold of. Things tend to be available from Australia and America, but you’re paying as much in postage as you are for the part.

“When the starter motor went a few years ago, I called up a guy in Essex who had one and he wanted £200. I said ‘bloody hell Mike, that’s a bit expensive’. He said ‘do you want it or not?’ He had it, I wanted it, and that’s the price, take it or leave it!

“I think now that I’m retired, I don’t want to spend too much money on it. If something catastrophic went wrong, like an engine blow up, that would probably be the catalyst to say ‘it’s got to go now’.

“I could not warrant spending £3,000 or £4,000 on a new engine.”

For now, though, the engine sounds in fine fettle as we head off towards the picturesque Reedham Ferry on the Norfolk Broads for some bright, but cold and windswept, photos.

And afterwards, it’s back to Barry’s garage, where packets of crystals are placed around the car to absorb the moisture that’s every 1970s Datsun’s greatest enemy.

It’s a battle that Barry has largely won for 43 years, and plans to go on fighting for a good few years yet.