Tim de la Fosse was a teenage boy when he was first seduced by the Jaguar XK120.

Back then, owning one seemed an impossible dream, but it didn’t stop him lusting after the car for decades.

“My friend’s dad was into motorsport, and I used to go round to his house and look at his motorsport magazines,” he says. “I remember seeing a 120 on the cover of a magazine and then reading the article aged 14, thinking ‘this is just beautiful’.

“From then on, whenever I saw a magazine in a shop with a 120 on the cover I’d buy it. I’ve always coveted the car, but when I was younger I could never afford one.”

That all changed in 2006, more than three decades later, when his wife Kathy, “the family chief executive officer”, gave him permission to stretch the finances.

At the time, Tim was a pilot with British Airways (BA) and, with three children still living at home, “we still had responsibilities, and we weren’t exactly flush”.

After flying into Nice overnight, Tim was sitting on the promenade drinking coffee the next morning, leafing through a classic car magazine.

He spotted a red 1950 XK120 for sale in Yorkshire, picked up the phone and made an appointment to go and look at the car.

“The owner had rebuilt it in 1982 and made a really nice job of it, but it had since been driven a lot and was looking a little tired,” says Tim, who flew helicopters in the Royal Navy before joining BA. “It was all a bit knackered, it wasn’t just patina, and it really needed some love.

“It was driveable, but the engine had thrown a valve, and it needed somebody else to take up the baton.”

That person was Tim, who parted with £27,500 and drove the car home to the west of Coventry.

“I put my foot down and it went well, even though one of the valves had burned out,” he says.

“But when you heard it idle it was thumping and banging – it really wasn’t very smooth at all. The carbs were leaking, oil pooled beneath the engine on the driveway – it really wasn’t very healthy.

“My first impression on driving a 120 was that you were sitting on the back of the car, with this massive bonnet out in front of you, and it felt really weird like being at the tiller of a boat. But if you look at it, the cockpit is actually in the middle of the car because you’ve got this huge boot behind you.

“I remember just going ‘yes, yes, I’ve finally got one!’, and I carried on doing that for some time. Every time I got in it I couldn’t believe I actually owned one.

‘There are a lot of wealthy people who own really nice XKs, and we weren’t really wealthy. It was a push to get it, thanks to my dear wife.”

The couple met as teenagers in 1977, when Tim was a police cadet, on a four-month tour through the Middle East to India arranged by a Ghurka colonel to celebrate the Queen’s Silver Jubilee.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“There were seven coaches with people from all over the Commonwealth, and Kathy was part of the Canadian contingent,” he says.

“We were on the same coach, and I spent four months courting her – or, as I say, four months of her chasing me.

“She flew back to Canada after the trip, but I eventually dragged her back over to the UK.”

Tim did little more than was necessary just to keep the Jaguar on the road for his first dozen years of ownership, “whatever was required to just keep it going”.

“Fairly soon after buying the car I took the engine apart, re-honed it, put new rings in, changed the valves, and things like that, and it went OK, but it was never quite right,” he says.

Despite its shortcomings, Tim used the car whenever he could.

“I used it for everything,” he adds. “You know, ‘do you want some milk darling? Oh, I’ll go down to the shops.’ I just drove it all the time, winter, summer, whenever I could, and I did lots and lots of miles.”

Longer journeys included two trips to France, and over to Guernsey, where many of Tim’s extended family live.

“But it was deteriorating all the time,” he says. “I always planned to do a proper rebuild, but never found the time.”

He was spurred into action, however, when a friend in the village bought an XK120 to rebuild.

“I helped him with it, and he did an absolutely beautiful job,” he says. “I thought ‘well, no, I can’t have that, it’s gorgeous, I’ve got to do mine now’.

“I went to a local classic car meet in the rain in September 2016 and I gave it a bit of welly on the way back, because I knew the whole thing was about to be taken apart. I drove it into the garage and the next day started stripping it down.

“The kids had finally left home, and I’d got some money I could throw at it. Just as well, because nothing is cheap for this car.”

That was in 2016, and Tim spent the next four years meticulously rebuilding the Jaguar, doing as much of the work himself as he could, despite no formal training.

For many years as a young man in the police and the Navy, he had to make do and mend with a series of old cars.

“In 1977, I had no money, my girlfriend was coming over from Canada, and I needed a car,” he remembers. “My mate had a garage and he had a Vauxhall Viva he’d towed off a motorway with a seized engine.

“He said I could have it but I’d have to put a Gold Seal replacement engine in it, which cost £250 I think.

“I knew nothing, but I bought a box of spanners from Woolworths, a Haynes manual, and put the replacement engine in. It started up, it went, and I had a car. One door was bashed in and Kathy came to a scrap yard with me and helped me strip a door off a scrap Viva. I knew then that she was a keeper!

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

“Then it’s been a case of through the years with kids, not having too much money, always having cars that needed hands on treatment to keep them on the road.”

One of those cars was a 1965 Morris Minor convertible the couple bought in 1983, with Tim honing his restoration skills with a rebuild at the turn of the millennium.

“We bought it from an old lady who worked at Bletchley Park during the war,” he says. “She was batty as anything, and the car was pink with black wings, with a gold monogram on each wing, gold painted switches, and leopard skin seats.

“It was tired, but we kept it on the road, patched it with filler, and sprayed it with underseal to get through the MoTs. It was our only car for a long time, and I commuted from Cornwall to the Midlands in it every weekend for a couple of years.

“I remember the Red Arrows were parked outside my squadron building at Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose, and the opportunity to park it in front of them was too good to miss (pictured).

“We then drove it from Cornwall to Prestwick in Scotland when I was reposted there.

“Eventually the engine blew up in the early ‘90s and we had it towed back to our house in the village and it just sat on our drive looking very sad and rotting away for several years.”

A decision needed to be made – scrap the car or restore it.

“So in about 2000 I sent the body to Charles Ware’s Morris Minor Centre, which was in Bath then, and they did the body for me,” says Tim, 65.

“They gave me back a nice shell, I rebuilt all the mechanicals and put it all back together.”

With that rebuild under his belt, in 2016 he was ready to tackle the more significant challenge of the Jaguar XK120, stripping every nut and bolt off the car.

The first 242 XK’s, which caused a sensation when unveiled at the London Motor Show in 1948, were entirely aluminium bodied.

Midway through 1950, the government gave Jaguar permission to use steel as long as they exported 95% of the cars.

Tim’s car is one of the 612 right hand drive roadsters that stayed in the UK, and one of the earlier steel bodied examples, though still retaining aluminium doors, bonnet and boot.

All of the cars were fitted with Jaguar’s 3.4-litre, inline six engine, capable of propelling the XK to 120mph, hence the name.

When he bought the car, it had been fitted with a later XK engine, which by 2016 was “tired and needed completely renewing”.

Finding parts was a treasure hunt that took him all over the UK.

“I spent a lot of time and money getting original bits and bobs,” he says. “I chased down trails as a treasure hunt to find the studless cam head in a barn in Norfolk. It was just a lump of crap that needed completely taking apart and re-fettling.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“Then there were the studless cam covers that were horrible corroded things in a barn in Chichester that needed stripping and polishing. Now they’re like glass, beautiful.”

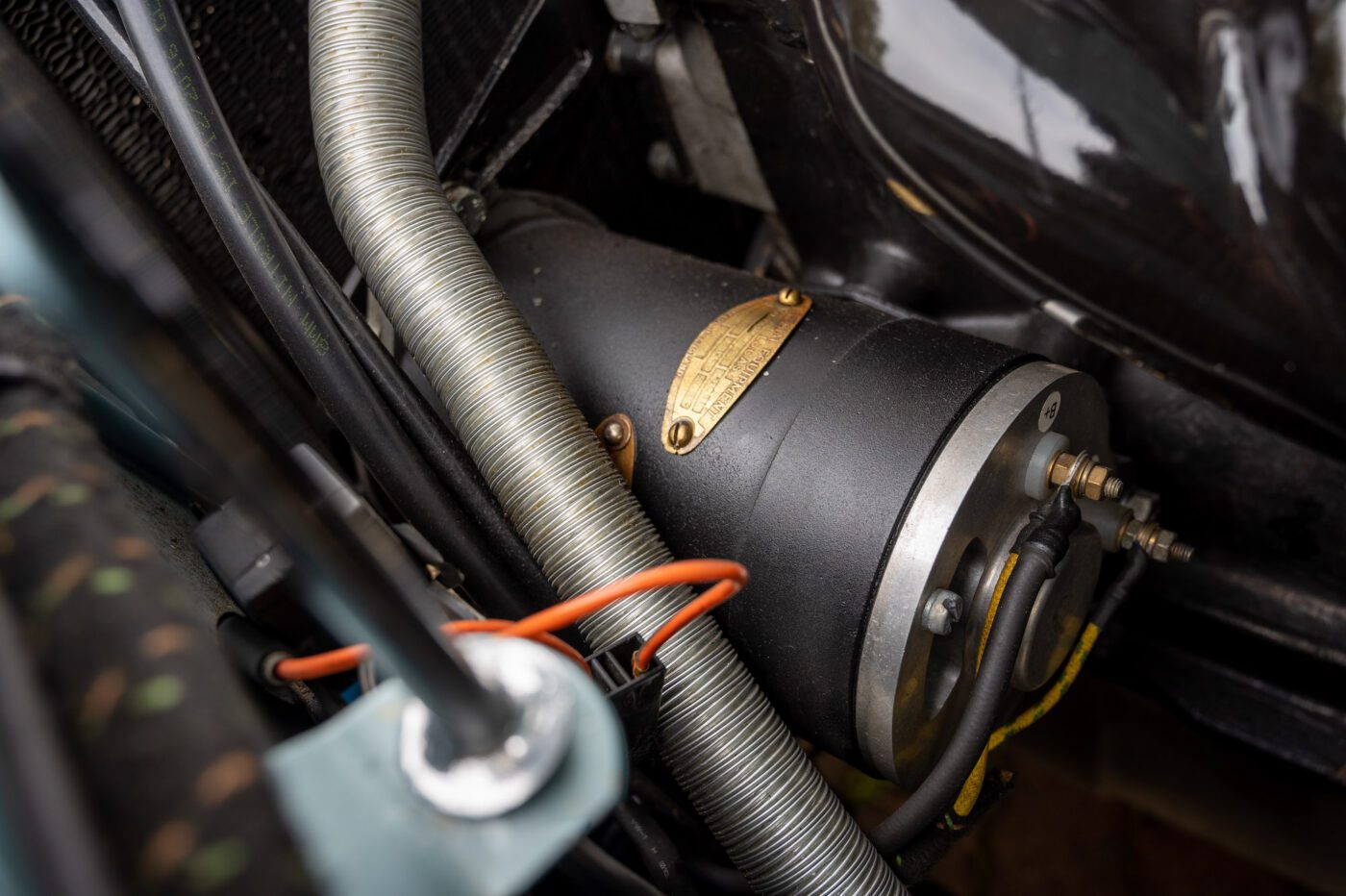

The engine was treated to new valves, pistons, piston rings, and crankshaft, and it was upgraded with higher lift camshafts and bored out for bigger valves.

“Inside, it’s more like an XK150 engine,” says Tim, “but it has the tall dashpot carbs of the earlier cars, so it looks original from the outside.”

A number of other parts were supplied by XK aficionado Tom Kent.

“You can get anything from a little grommet to an engine from him, and you know it will be an original part,” he says. “He was fantastic – you can get the smallest things from him, even the brass top of a carb.”

Tim did as much of the work as he could, dismantling the car and recruiting specialist help where needed.

“I can weld, but not good enough to do a 120, I can’t upholster and I can’t paint to that standard,” he says. “Everything you can see, the bodywork, the trim and the paint, I’ve not done. But what I did do is get it all done and put it all together. I rebuilt it mechanically, reassembled it, rewired it, and got everything mechanically in place, and it now goes beautifully.”

The car was finally finished in August 2020 and, for the first time since he bought it 14 years earlier, it was running exactly as it should.

So what was it like to drive?

“Terrible,” laughs Tim. “It’s a 1940s car and they just aren’t as comfortable and advanced as a modern car.

“You get in a modern car and it’s almost a relief because it’s so lovely to drive, but with the 120 you’re driving a piece of history and a piece of sculpture. Flying a Spitfire would not be as comfortable as sitting in a 747 in first class, but that’s not why you’re doing it.

“You’re driving a piece of history and you’re driving in the mode that was driven 70 years ago. “As an experience, it’s fantastic, and if you crave attention, which I must do, then you get it in spades. Everything stops and looks as you go past which, if you’re a bit of a show off, which I am, is great!

“I still look at it and think ‘it’s just beautiful’. It’s not just a car to me – I’m besotted with the thing, I really am.

“Even just as a sculpture, if it wasn’t a car, I think it’s fantastic, a gorgeous shape.

“There’s only one other car that I think is just as pretty, and that is the Bugatti Type 57 Atlantic, but they’re £10m – it’s a different league.”

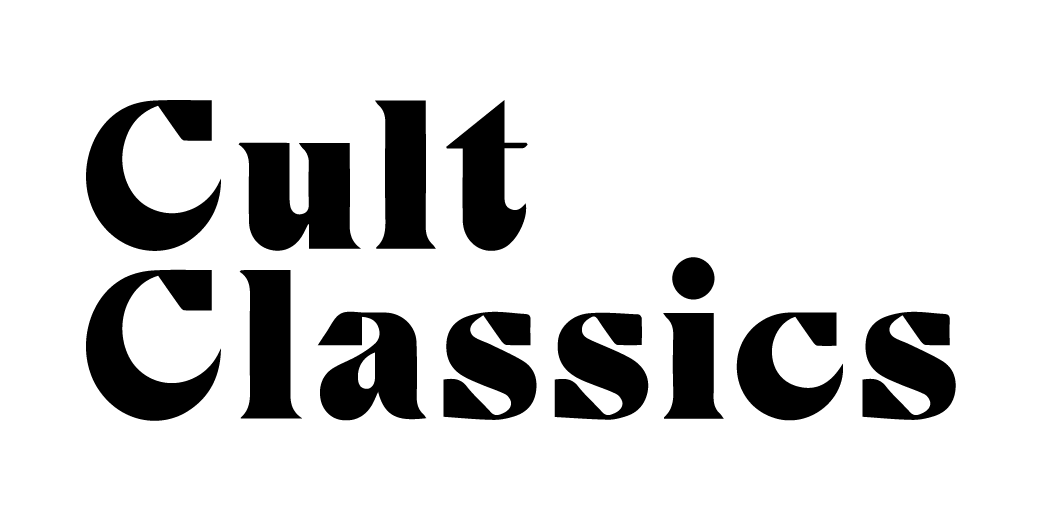

Another piece of history that’s special to Tim is embedded in one of the aluminium panels underneath the car.

“British Airways was scrapping some 747s, and they took the fuselage of one of them, cut little pieces of metal out, printed a picture of Boeing 747 G-BNLJ, and gave a piece to each BA pilot,” he says.

“Mine is bonded into a panel underneath, so that part of the car was once a 747, and it’s a 747 I’ve flown around the world.”

It was always Tim’s intention to build the car to concours standard and enter it into some competitions.

“I knew, also, that I wouldn’t keep it at concours standard,” he adds, “because I’d drive it, and it would be all downhill after a couple of years with stone chips and all the rest of it.”

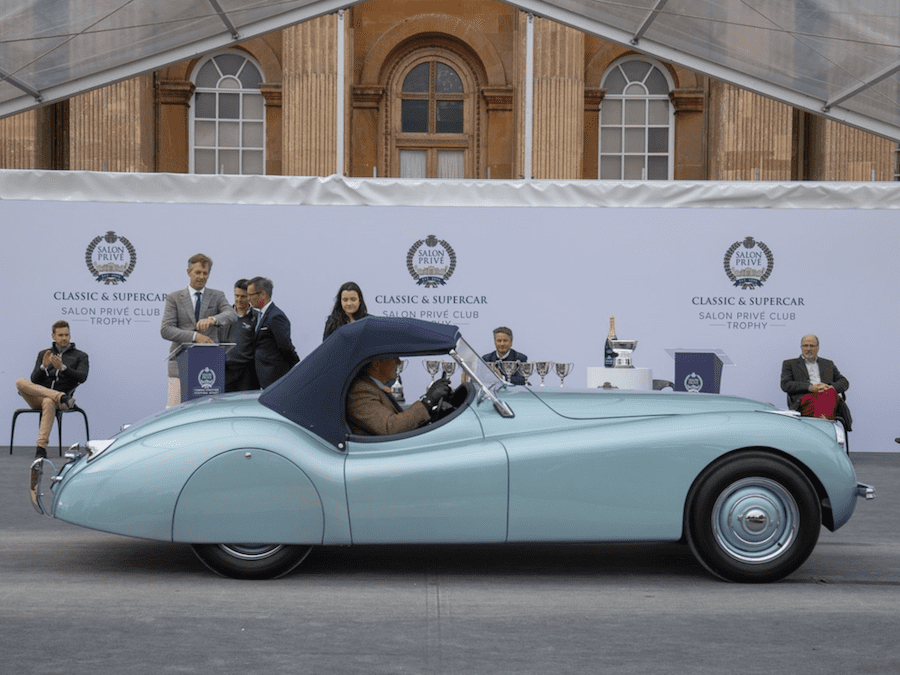

But, after winning a Jaguar prize at Salon Privé at Blenheim Palace in its first year, followed by success in the pre-1960s class at Hampton Court’s Concours of Elegance in 2022, the prizes just keep coming.

“We won the Jaguar trophy at Hampton Court again this year,” he says, “so here we are three years on, and it’s won another prize.

“There are now stone chips, it has got scratches, it’s showing some wear and tear you get from driving 7,000 miles.

“But that’s life, I’m fine with it. I put a small chip in the paint on a wing when a piece of metal fell against it. It’s tiny, you can’t see it very much, but I know it’s there. If you know where to look there are little tell-tale signs, but that’s OK. It’s a car to use.”

Tim has been told its concours success will add to its value, but it’s all academic.

“I’ll never sell it, so it really doesn’t make any difference to me what it’s worth, and anyway classic car prices are plummeting,” he says. “A lot are owned by old blokes and old blokes are dying, so more cars are coming to market.”

The Moggie, too, will never be sold (“I can’t sell it because it’s Kathy’s – I think it would be divorce”), and the cars both attract attention in their own ways.

“People stop and look at the Morris with a big smile on their face – isn’t that cute? But the XK just has presence,” says Tim, who flies and displays old aircraft for the Royal Navy, including the Wasp helicopter and Harvard fixed wing aeroplane.

“An aunt of Kathy’s was over from Canada. She looked at the Jaguar and said ‘oh, that must be a babe-magnet!’. I said ‘no, it’s an old man magnet, that’s what it is’.

“You get lots of old men round it wanting to know all about it. You do also occasionally get young ladies in petrol stations say ‘absolutely gorgeous’, to which I always reply, because it’s predictable, ‘but what about the car?’”

Since its restoration, the XK120 has been back to Guernsey, but Tim has one dream left to fulfil.

“I want to take it back to the promenade at Nice, where it all began, and drive her along there,” he says. “I think we’re going to take the ferry down to Santander and drive along the north coast of Spain, the south coast of France, to the promenade of Nice and then drive it home.”

Sometimes, the dreams of teenage boys do come true.