As a car enthusiast born in Bradford, Graham Austin was perhaps always destined to fall in love with the Yorkshire city’s native car.

He had already owned a couple of pre-war Jowetts, unfinished restoration projects, when in 1991 he was looking around for a sports car to take him back to his youth.

Initially, the focus was on MGAs and TR4s, but then a visit to Jowett expert and friend Ian Priestley changed everything.

“He asked me if I had anything to restore and I said no – I was running a 1930s Vauxhall at the time,” says Graham. “Then he told me he’d had a phone call from a lady in Gloucestershire who had a 1952 Jowett Jupiter in her barn, and was I interested?

“That was on a Friday, I rang her straight away and I was knocking on her door at half past nine on the Saturday morning. She couldn’t believe I’d come down that quickly to see it.”

The Jupiter (pictured in and out of the barn), in its original turquoise metallic blue, had been put away on blocks in the barn in 1980, and Graham says that, on first inspection, “it looked in one piece and mostly there, but I didn’t know anything about Jupiters”. So he called another friend who did know about Jupiters on an early mobile phone and walked and talked around the car.

“He talked me through what I ought to be looking at and whether it was a goer or not,” he says. “Eventually we decided it would be a suitable candidate for restoration, so I made her an offer.”

Graham agreed to pay £3,250, and left a small deposit before heading back to Bradford, intending to return the following Saturday with a trailer.

Then the first of two hitches struck, with the seller calling to tell Graham she’d had a better offer from a trader.

“I’d put a deposit down so it was a bit cheeky, but I put more money on the table, took the next day off, roped in my dad and step son and went down with £5,000 in cash,” he says.

“At the time, for that car in that condition, it was quite a lot of money, but I wanted it and restorable ones were thin on the ground.”

That’s hardly surprising given about 450 of a production run of 825 factory built cars and 75 coachbuilt cars survive, with many overseas.

Hitch number two came when Graham and co had loaded the car onto the trailer, ready for the long journey back north when a car came up the drive and blocked them in.

“It was the lady’s husband, it was a divorce sale and he said ‘what’s going on here?’” he laughs.

“He went into the house in a storming temper, came out and said ‘how much have you paid for that car?’ so I told him. They had a bit of a conversation and he suddenly broke out into a smile and said ‘yeah, that’s all fine, I’m happy with that’, moved his car and let us out.”

Graham’s newly-acquired car was finally back home in Bradford, 39 years after it rolled off the production line in July 1952.

The Jupiter had been launched two years earlier as the Javelin Jupiter, Jowett hoping to take advantage of the saloon Javelin’s motorsport success and move up a gear into sports cars for export.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

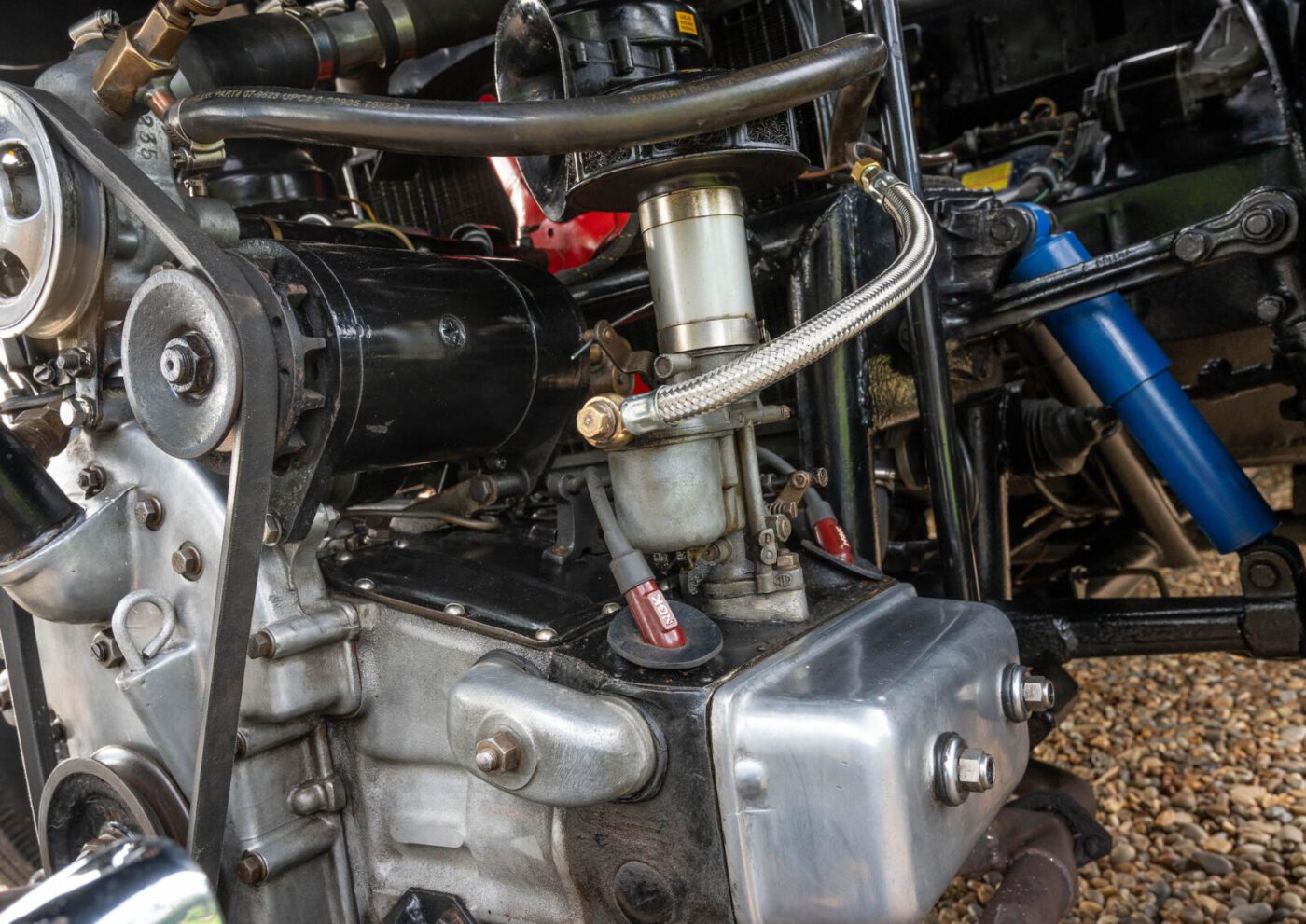

They used a tuned version of the same 1486cc flat four, overhead valve engine, plus the same gearbox, back axle and some suspension parts that helped the saloon become one of the most advanced cars of the immediate postwar era, with a class win in the 1949 Monte Carlo Rally.

Austrian engineer Eberan von Eberhorst, drafted in by Ferdinand Porsche to work on Auto Union race cars, came to England after the war to work for ERA and was asked to develop the tubular chassis, which later required strengthening on the production line.

Meanwhile, Jowett’s own Reg Korner designed the steel-framed aluminium drophead coupe body with a brief, says Graham, “to make it look like a Jaguar”.

The Jupiter got off to the best possible start, winning its class at Le Mans in 1950, and following that up a year later with a class one-two in the Monte Carlo Rally. Various other international successes followed.

Graham’s car was first sold in Cirencester in August 1952 and, after a long search, he tracked down the original owner, who had bought it for his son as a wedding present.

“He used it for three or four years, but then his wife got pregnant and couldn’t fit behind the steering wheel so he sold it,” he says.

From there, the Jupiter turned up in the Jowett Car Club (JCC) in the ‘70s before moving to Scotland, to the Midlands, and finally back to Cirencester.

“Its owner had gone to the Prescott Hill Climb at the Bugatti Owners Club and parked it in the car park with a for sale notice, and the chap I bought it from saw it and bought it because he loved the shape of it,” says Graham.

“But he knew nothing about Jowetts, and he knew nothing about cars, so when it had problems he pushed it into his barn, put it on some logs and left it.”

When Graham got the Jupiter home, it quickly became clear that it was nowhere near as good as it had seemed on the surface, with lots of missing parts.

“There were lots of things wrong with it – the sills were rotten out, and the body was rotten in parts,” he says. “But I put a battery on it, put some fresh fuel in it, and it fired after three or four attempts. At the time I had a driveway on an estate with half a dozen houses all quite close, and because it had been stood for so long a squirrel or something had stuffed nuts, straw, moss and rubbish up the exhaust pipe. When it fired, it went with a bang, and blew this cloud of crap, along with carbon dust, rust and blue smoke, all over the neighbours.”

He clearly had a decision to make – do it up to the point he could run it, or carry out a full restoration.

“I ummed and aahed, but it really needed to be done properly, and the only way to do that was to take it to pieces,” says Graham, 73, a retired IT consultant.

“I stripped it right down to the chassis, which was shot-blasted, and worked up from there. I prepared the bodywork as best I could (pictured) and had it finished by a pro.”

The single bench seat – billed as a three-seater – was reupholstered, along with a full interior retrim, and the brightwork rechromed, while Graham got hold of a wiring loom and re-wired the car himself.

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

“I did everything that needed to be done to make it into a reliable, nice-looking car,” he says, aided significantly by the JCC and the network of Jowett enthusiasts grouped around the car’s birthplace.

Through his previous Jowetts, Graham had been a member of the JCC – the oldest one-make car club in the world – for about 12 years, as well as the Jupiter Owners Club.

“The JCC has a fantastic stores operation, and the stores and all the expertise was in Bradford,” he says. “Anything I needed to know, any parts that I wanted, any information I needed, I could pick up the phone and get someone down to look at it. You can’t run a Jowett without being in the club, it’s just not practical.”

So what of the metallic turquoise blue paint?

“It was very unusual at the time, but Jowett liked metallics, and the chap who ordered it obviously thought his son would like it,” says Graham. “But it wasn’t the colour for me, it just didn’t do it for me. So I had to make some crucial decisions.

“I’d always wanted a sports car in British Racing Green, and this is a Jaguar colour, as the Jowett BRG had too much yellow in it for my taste.”

After four years of work, the car was finished in November 1995.

“I took it for its first MoT, and I knew the tester,” he says. “It staggered through the test. These days you’d get advisories, because there were one or two things that were not quite right – a buckled wheel, and the brakes stopped but were not efficient.

“I ran it all that winter, in the thick snow in the north of England. I was a bit keen, but I’d spent four years doing it and I wanted to use it, so I just took it out.”

Having made it through a Yorkshire winter, Graham sought advice about taking it across the Pennines to the JCC show at Tatton Park in Cheshire in May ‘96.

“It wasn’t particularly running that well and I took it to a friend of mine and he said ‘well, not sure about taking it to Tatton Park’,” he says. “I thought ‘sod it’, so I entered it and went from Bradford to Cheshire and back, which is quite a way. I came away with joint best OHV and best Jupiter, which I was really pleased about because I didn’t do it to a standard, I just did it. So it spurred me on.

“The engine wasn’t right though, so I took it out and had it rebuilt by a specialist. Somebody had put the pistons in back to front, which wasn’t good. The guy said he wasn’t sure how I got to Cheshire and back…”

The Jupiter was in regular use for about 10 years, less so in the winter to protect it from the heavily-salted Yorkshire roads, taking Graham and his then wife on car rallies and holidays to the coast.

“It was out every weekend between April and October, and on nice days I’d go for a run to the pub to meet my friends,” he says, before disaster struck.

“I’d had the car in my dad’s garage, but when he passed away the house was sold so I needed to get it out. While moving it, it blew the engine – a con rod broke at the bottom, and absolutely destroyed the engine completely.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“It bent the crank, smashed the crankcase, and put the camshaft into three pieces. It just wasn’t economically repairable.”

Replacement engines are not exactly easy to find and, but for the ingenuity of the members of the JCC, Graham’s car may have been off the road for a lot longer than the 18 months it took to build a new engine from scratch.

The Jowett engine features an unusual aluminium block in two pieces that are joined together at the crankshaft centre line, with the alloy provided by metallurgists from nearby Keighley Laboratories.

At around the time Graham’s engine gave up the ghost, the JCC was in the process of remanufacturing the block and crankcase, with an improved, stronger alloy supplied by the same metallurgists.

“They had the original factory drawings, the original metallurgist, and some fantastic engineers in the club,” he says, “and they made a new cast in two halves out of a new alloy.

“My friend Ian was instrumental in all of this, and he wanted someone to be a guinea pig to test out the new engine, and I said I’d do it. I put the money in to buy the parts and they put the expertise in to build the engine.

“The block in there was second off the production line, and uses slightly modified Fiesta pistons, with a brand new remanufactured camshaft. All the other parts were the best we could collect together that we couldn’t remanufacture.

“An elder statesman of the club called Jack Mitchell put the engine together. It was the first brand new engine to be built from when the Jowett factory closed down in ‘54.”

In all, 50 new crankcase pairs were made by the club, and Graham’s has been in situ for 17 trouble-free years.

“I don’t like talking about it,” he laughs, “but it’s been no trouble at all, it’s been absolutely brilliant, and it’s been all over the place.”

The Jupiter may be 70 years old, but Graham says its sofa-like seating is more comfortable than his modern Land Rover Discovery, and the “fantastic” handling and slick column gearchange make it a “beautiful drive”.

“I’ve done 200 miles in it from Bradford to Stevenage, where we used to have a home, and it’s very comfortable,” he adds. “My bum’s hurting after the same journey in the Discovery.

“It’s not the fastest thing, but it would do 90mph all day. The engine runs and runs and runs at maximum speed.”

Over the years, the Jupiter has given Graham a “huge amount of fun”, featuring in his step-daughter’s wedding and winning two national Jowett concours awards as well as the holidays and fun drives out.

He decided to stop entering competitions in 2001, but couldn’t escape entirely thanks to the enthusiasm of his second wife, Lorraine.

“It was in 2008, I think, and we went to quite a big rally on the east coast in Yorkshire, and there was a slip that said ‘judging/no judging’ and I put ‘no judging’,” he remembers. “Lorraine said ‘you’ve never judged this car while I’ve been with you’, so I said ‘if you want it judged, I haven’t cleaned or polished it, you put the thing on’, so she did.

“We went down for the judging and they said ‘the OHV car of the show is Graham Austin’s 1952 Jupiter’, so I got the cup, but the jumble was closing up and I wanted a polishing cloth, and off I went.

“I was just getting it and I heard the guy say ‘the final show winner, best car of show, belongs to Mr Graham Austin’. I ran down the field and I said ‘what did it?’ There were some cars there worth a million and a half, and he said ‘it was the car I wanted to see in my drive’. I thought ‘fantastic’. But that was it, no more competitions.”

With so few Jupiters on the road, Graham’s car attracts plenty of attention at shows and on the road.

“When you go to a car event, very often you’re the only Jowett there,” he says. “You do get ‘my dad had one’, but not a lot of it. It’s more likely to be ‘I’ve not seen one of these in years’, or ‘I’ve never seen one of these, what is it?’ People are very enthusiastic, and it’s nice in a way because for lots of people it’s their first introduction to them. It’s always very popular and always gets a good reaction.”

Since moving to Norfolk seven years ago, Graham is no longer surrounded by his Bradford Jowett community – he used to work in the club’s warehouse on a Monday night – and most of the Anglia region club events are in Essex.

“If I want to go to a JCC pub meeting it’s a 250-mile round trip, whereas before it was a 20-mile round trip,” he says, “so now it’s just local car shows and events.”

But there is one important milestone on the horizon, the 100th anniversary of the JCC in Yorkshire in 2023, and Graham is determined to make the trip in the Jupiter.

And after that?

“It’s a tricky one – but it will have to be sold eventually,” he says. “I’ve got a daughter who originally said she’d like it, but she hasn’t the capability to look after it, and her husband is not mechanically minded, so I think she’s decided that it’s not going to be practical.

“Most of us with these cars are of a certain age, and one or two of my friends have passed away and their wives have been stuck with cars and piles of spares.

“I’ve got a garden hut that’s literally bursting at the seams with 16 boxes of spares, more spares in wardrobes in the garage, another hut with boxes of spares in, three axles hidden behind the wheelie bins, a spare engine, two spare gearboxes.

“All that will have to go with the car. I’ve got enough stuff, if you bought that car you could run it for years and not spend another penny.

“It would be a wrench but it will have to go sometime.”

But not just yet…