Walking around Martin Cliffe’s assorted barns and garages, it’s hard to know what to drool over.

There’s the Lotus Esprit Turbo that Martin helped develop in his time at Hethel, and the Ford GT40 replica that’s almost indistinguishable from the real thing.

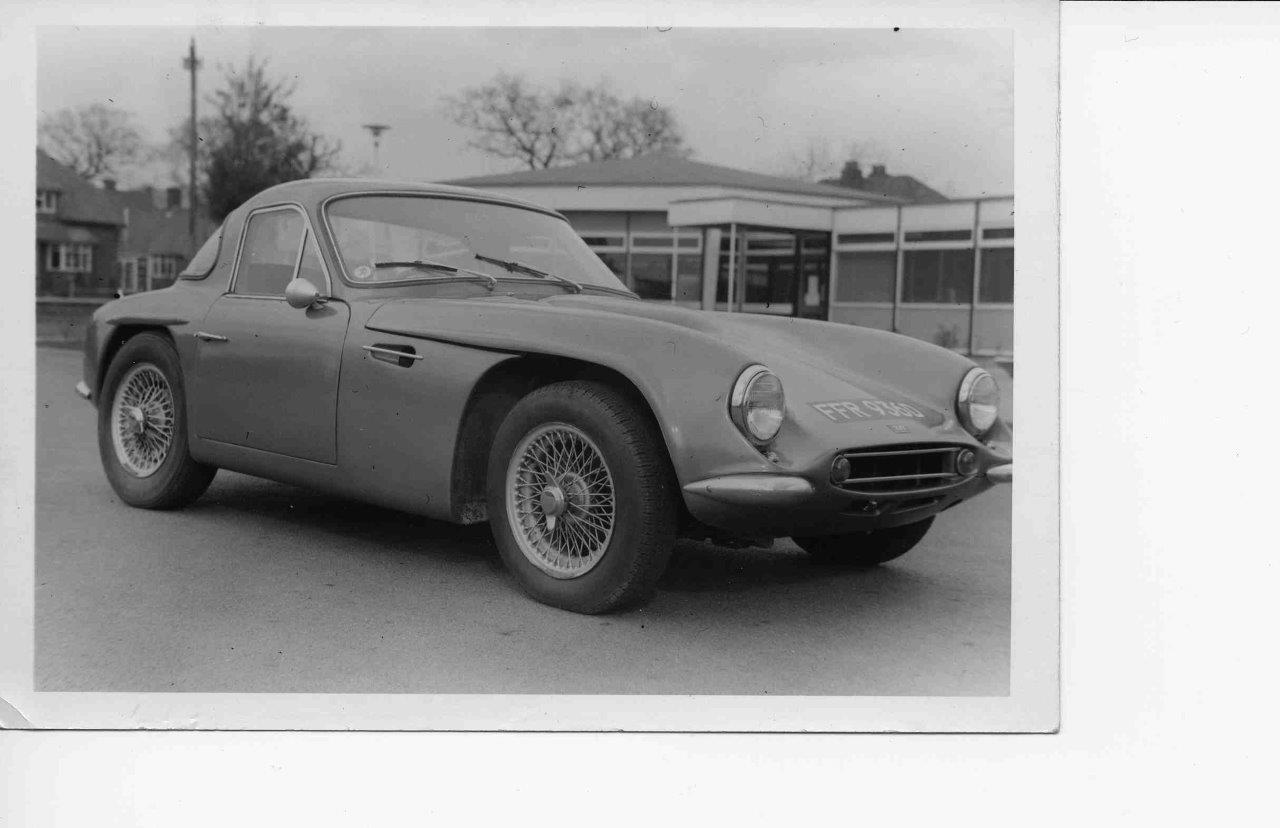

Stunning though they are, they are relatively recent acquisitions, and this is Forever Cars, so we’ve come to talk about the bronze TVR Grantura III he first bought in 1966 (pictured) and has since sold and bought back twice.

Then there’s the small matter of a Lancia Stratos HF that Martin paid £19,000 for in 1984, an inflation-adjusted snip at £55,000 in today’s money.

And this one definitely is the real thing, one of fewer than 500 road cars built for homologation purposes to allow the rally car to conquer the world between 1974 and 1976.

But first, back to 1966, and a man called Carl Smith, who was a trimmer at TVR’s Blackpool factory.

The company was always in financial strife, and Martin believes Smith had acquired the car at least partly in lieu of wages, building the Grantura from a mixture of parts, including a Griffith bonnet, between 1963 and 1966, when it was first registered.

“They were always skint and everything was always going wrong for them,” he says. “They were actually quite good cars, but they weren’t properly financed and they were run terribly badly until Martin Lilley took it over and brought some stability to it.”

Having spotted the car for sale in Exchange and Mart, Martin headed from south of Manchester, where he was living, to Blackpool.

“Carl wanted to get married, and he needed the money so he put the car up for sale,” he says. “I thought it was fantastic, the performance was wonderful, the noise was great, and I had to have it. Because he was a trimmer, I’m sure it was the best-trimmed TVR of any car they ever made – he’d done it beautifully.

“Somehow I raised the money and sold my first car, which was a Hillman Imp. I drove it back home and used it as an everyday car.”

Martin was 21 at the time, and half-way through a sandwich course in mechanical engineering at Salford University, also working for Renold Limited, which made chains and power transmission products.

“I used to go to work in it every day and did a few bits of very mild motorsport, 12-car rallies and economy runs and things like that,” he remembers. “Elizabeth and I did our courting in it – you’d think it might be impossible in such a small car, but we won’t go into too many details…”

After a couple of years, Martin part-exchanged the TVR for a Ginetta G4R in Lowestoft that had hitherto only been used for racing.

“He’d only put it on the road to sell it,” he says, driving it back to Cheshire on a Monday night. “I wouldn’t consider doing it now, a car that had only been used on the track. It was quite a hairy thing – very noisy, very quick, very crude, but great fun.

“From Tuesday to Friday I went to work in it, and on Saturday I went to the local filling station, filled it up with fuel, and went round to my best mate in it to show him what I’d bought. On our little test drive it caught fire, and all I was left with was a pile of steel tubes covered with this kind of shredded wheat. The only thing that was intact was the fibreglass petrol tank still full of fuel.”

Martin’s life carried on without the Grantura for the best part of 20 years, during which he had worked for Ford on engine testing at the company’s Dunton research and development centre, before moving on to Holset in Huddersfield and working as a technical sales engineer on turbochargers.

One day in 1979, he was asked to attend a trade show at the NEC in Birmingham, and went along with Elizabeth, who got chatting to Colin Chapman on the Lotus stand.

When she told the great man that Martin worked on turbochargers, he said to her: “I want him here on the stand at 2pm.”

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“I thought she was making it up,” he says, but found himself being interviewed by Chapman, managing director Mike Kimberley, finance director Fred Bushell, and engineering director Tony Rudd.

They wanted him to breathe new life into the Esprit’s underpowered slant-4 engine by developing a turbocharger to give the car the performance its supercar looks deserved.

Bolting on a turbo was considered quicker and cheaper than developing a new V8 engine, and Martin got to work under powertrain engineering manager Graham Atkin, who was involved in a serious car accident soon after.

“We used to have engineering meetings in his hospital ward, and then by his bedside when he was recuperating at home,” he remembers. “His wife would chuck me, saying ‘you’ve been here long enough, he’s getting tired’.

“I was dropped in at the deep end but, despite time and budget constraints, we managed to do it, and it provided the Esprit with supercar performance, 150mph and 0-60 in under 6 seconds.”

With the project complete, and Lotus entering one of their fallow periods, Martin considered jobs at Garrett AiResearch, Ford, and Hesketh Motorcycles before opting to remain in Norfolk and set up Omicron Engineering.

Engineering and turbocharging consultancy was gradually overtaken by restoration work, focusing on Lancias but also taking on exotics like Lamborghini Miuras, Ferrari Daytonas and, in the early days, a Maserati Khamsin.

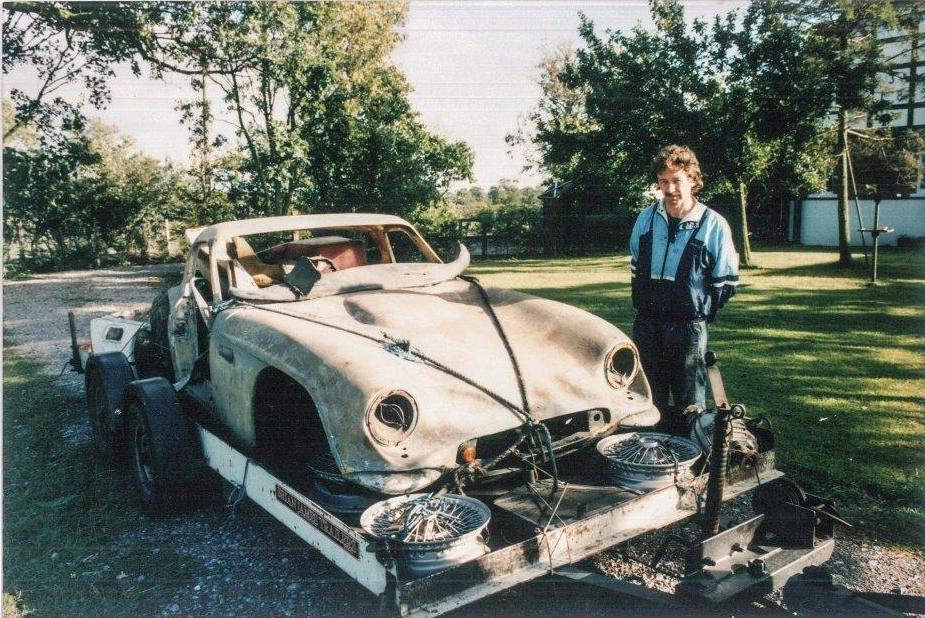

Martin had already bought the Stratos by the time he saw an advert for a TVR Grantura with a Griffith bonnet in a classic car magazine in 1988.

It was, indeed, ‘his’ car (pictured with Carl Smith), but the dealer told him it had already been sold to a customer in Sweden.

“I was a bit disheartened by that, but I got into correspondence with the Swede and he sent me some photographs of it and it was in a terrible mess,” he says. “It had obviously been in quite a serious accident, all the back had been destroyed and someone had used chicken wire and bits of wood to try to build up some sort of maquette to form the fibreglass on. But it was horrible, so I was quite glad that I hadn’t got it.”

However, a few years later, the dealer got back in touch. The Swede had never collected the car, despite paying for it.

“Like an idiot, I got in touch with him and negotiated a price,” says Martin, who collected the car from Lancashire and popped in to see Carl Smith, who by now was working for Rolls-Royce at Crewe, on the way home.

“He said ‘if you can restore that, I’ll retrim it for you’. I don’t think he meant for free. I thought that’d be great to close the circle.”

But, despite some initial work, the putative project ground to a halt because Martin couldn’t find a mould to reproduce the rear section of the car.

After three or four years, the TVR was part-exchanged again, for a racing Ginetta G4R, again.

Martin kept track of the Grantura, which was in the process of being restored and converted into a racing car, but the episode had a sorry ending.

“I phoned him up one day in about 2016 and said ‘how are you getting on with my TVR?’” he says. “He said ‘not very well’, and it turned out he’d been unsatisfied with the work done on it and had taken the restorer to court.

“He didn’t think it was fit to turn into a racing car, so I went and looked at it in Sussex or Surrey. “He’d had it in a semi-finished state for several years and he showed me all the parts that came with it, but there didn’t seem to be everything there.

“It was going to be a mammoth project – do I really want to do this? I had enough things to do, so I said no and walked away.

“However, on reflection, I decided I ought to do it and I bought it off him, but it was in a terrible mess (pictured in green).”

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

Martin started work on the car in 2017, and three years later it was finally back on the road.

The body was blasted to remove paint (pictured), filler and gelcoat, before an ex Lotus employee – a fibreglass specialist – sorted out the damaged rear end.

A Peugeot bronze was chosen for the bodywork, while the interior was retrimmed in vivid red vinyl, with carpets to match, and a new wood grain film dash was created.

Under the bonnet, the car came with a race-tuned MGB 1800cc engine that Martin rebuilt with a Kent Cams high-torque camshaft and new bearings.

About 50 years after he had last driven it, the TVR was back on the road in Martin’s hands, and it felt good.

“They say you should never revisit things, don’t they, that your memories lie and things are never quite as good as you remember, so I didn’t have high hopes,” he says. “I thought I’d be disappointed, but I wasn’t, and it’s really nice and bears comparison with a lot of other cars of the time.

“TVRs don’t have a very good reputation, and I don’t know why – they’re very cleverly designed cars, and they handle wonderfully. The original suspension used VW Beetle torsion bars and trailing arms, which gave a rock hard ride and incorporated rubber bushes, which lead to chronic rear wheel steering. But once they’d redesigned that, it’s a nice supple ride, and it handles really nicely.”

On one of its first trips out, Martin parked the car at an air display at Marham, when he noticed a man walking around it and looking intently.

“He said ‘I used to have one of these, exactly the same colour inside and out’,” says Martin.

The man was Geoff Hipperson (pictured), at the time Mayor of King’s Lynn, and it turned out he had bought the car in 1968.

“The car was featured in Classic Car magazine, and his worship came along to lunch with us, and that was really nice,” says Martin.

Throughout this period, other cars came and went, but the Stratos remained, one of a dwindling number of original cars on UK roads.

Martin’s interest in acquiring one was piqued when Omicron looked after a Stratos owned by Ian Fraser, former owner of Car magazine and other titles.

“I enjoyed driving it and, while I knew of Stratos’s before that, I thought it was a great car and I thought I ought to try and get one,” he says, his search taking him to Dachau, Germany, where Car’s continental correspondent Georg Kacher had discovered one for sale.

“He was very helpful in going through all the various government departments, because it was quite a palaver getting these special export Zoll plates and compulsory insurance, plus paying some tax that you got back if you had the paper stamped when you left Germany.

“I stayed the night there and set off the next morning, driving back to the Hook of Holland. I think it’s about 600 miles, and I did that all in one sitting, apart from stops for fuel and comfort breaks. “I didn’t have anything to eat, and I got close to the Hook of Holland and I had to stop – I was dead on my feet, except I was on my arse. I went into this hotel, and it was quite late at night.

“I said ‘any chance of a meal?’ They were closed, but they rustled me up ham, egg and chips, and it was the best meal I’ve ever eaten. It was just wonderful and it saved my life.”

Given the Stratos’s tiny dimensions – not much longer than a Mini and six inches lower – how were Martin’s limbs after such a journey?

“I was OK, they’re quite comfortable cars,” he says. “It’s quite a small car but there’s loads of room in them. Once you’re in it’s very easy to drive. But I was a lot younger then – I probably wouldn’t even think about doing it now.”

Martin believes his car, chassis number 1994, was one of the last produced in 1975, by which time the rally car was already a world champion.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

Built specifically for rallying, and inspired by the concept Stratos Zero, also designed by Bertone, all the cars – both road and rally – were fitted with the 2.4-litre V6 from the Ferrari Dino 246.

Enzo Ferrari was initially reluctant to supply the engines to Lancia, and Martin says the Fiat 130 V6 and the 2-litre Lampredi unit used in the Beta were considered as alternatives.

It’s believed Ferrari saw the Stratos as competition to the Dino, but with production of the latter ending in 1974, the way was clear and 500 engines were supplied to Lancia.

The road cars were rated at 190bhp (later rally cars pumped out up to 320bhp), good for 60mph in 6.8 seconds and a top speed of 144mph.

“It goes quite well, and in the context of the time I suppose it was a very fast car,” says Martin, “but now any sort of hot hatch will run rings round it in terms of acceleration and probably top speed and cornering ability. Any car has got to be viewed in the context of its time.

“It’s got a reputation of being a very difficult car to drive, because it has a rather short wheelbase, but it’s actually a pretty good road car.

“I think it depends how you drive it – if you drive it circumspectly, it’s fine, it doesn’t catch you out and it’s got a comfortable ride. The boot is big enough to take golf clubs if you’re stupid enough to want to play golf.

“But if you press on a bit you end up in trouble, and I think you need to be a super driver, which I’m not, to be able to drive it fast safely.

“It’s mid-engined, but only just, and it behaves like a Porsche 911 with lift-off oversteer. That’s fine in moderation, but something you regret when taken too far – you have to keep your foot in, because if you take your foot off you’re going to lose control on a bend.

“The only time I had a serious problem was coming off the M25 onto the M11 and there’s a big sweeping bend which you think you can take at any speed, but it gradually tightens up on you.

“I was pressing on a little bit and thought ‘I’m not going to get round this corner, I’d better slow up a little’, so I did and that’s when I got this massive oversteer situation and I lifted on the tail. “ I got round it, and the car was undamaged, but it was a heart-stopping moment, a change of underpants job.

“Up to a point, you can exploit that – you go into a corner possibly slightly too fast, lift off and it makes the nose tuck in delightfully, and you can steer it on the throttle and play at being a rally driver. You think you’ve cracked it!”

In conversation at a Stratos event in Austria with actual Lancia rally driver Sandro Munari, Martin quizzed him over the car’s ‘toe out’ set up, where the rear wheels are closer together at the rear than the front.

“If you’ve got a rear wheel drive car it has to have toe in to be stable, so I said to him ‘this makes the car unstable’,” he says. “He said ‘yeah, this was deliberate, to make it an unsettled car, because when you’re going into a rally you never know if the corner is going to go left or right and you’ve got to be able to swing the tail around to get it right’.”

Something to remember if you’re ever fortunate enough to drive a Stratos on the road…

It’s a privilege afforded to very few these days, with the cars reaching stratospheric prices, long after Lancia could barely give them away in the 1970s.

“Nobody wanted them – too weird,” says Martin. “A lot of cars that end up worth a lot of money go through a period when they’re not worth anything, like D-Type Jaguars and Ford GT40s.

“So they went into Lancia dealers as what the Americans called ‘showroom traffic builders’ – come to look at the Stratos and buy a Beta.

“They were also given to well-known personalities and sporting people to be seen in them.”

Unlike the TVR, Martin has never had to rebuild the Stratos, and has used it sparingly over the years, often to attend Lancia Motor Club events.

“It’s probably been driven by more journalists than me,” he smiles. “It’s always being borrowed by people – Jeremy Clarkson borrowed it for a video, Sony took it to Silverstone to film it for one of their Playstation video games, and it’s been to numerous photographic studios.”

When Martin bought the car, there were maybe 30 on the road in the UK, but most have now gone overseas, many to Japan.

The number remaining is in the low single digits and this, combined with their price tag and desirability, explains the market in legitimate replicas and, as Martin discovered, illegitimate clones.

When he received an email from Stratos aficionado Thomas Popper, he had cause to be alarmed.

“He said ‘please be aware there’s a car for sale in Italy with the same chassis number as yours, here are the details’,” says Martin. “I found out it was also for sale in this country with a dealer in London, so I told him I was interested and could I have some photos of the chassis number and plate.

“Sure enough it had the same chassis number but, whereas on mine the numbers are all very nicely lined up, on this one they were all a bit higgledy-piggledy, stamped on by hand not very well. Unlike the kit cars, this was almost indistinguishable from the real thing.

“I didn’t really know what to do about it, but Thomas was very insistent that I ought to do something.”

Martin flew to Turin to speak to Italian police, where he met Popper and the local constabulary.

After providing a paper trail to prove his car’s authenticity, he expected the rogue car to be seized.

“I didn’t want it to be crushed – it was too good to crush, but it ought to have a different chassis number,” he says, “but nothing ever happened about it, the car was sold and someone’s now using it as a competition car.”

Martin’s only remaining option was a civil prosecution, at a cost of €30,000…

“I said to myself ‘am I going to benefit from this by €30,000? Probably not, but if I came to sell the car it would still put people off…”

Note to prospective buyers – always look closely at the chassis number and, if in doubt, get in touch with Thomas Popper.

Through all this, Omicron had become a renowned Lancia specialist, with Martin, now 78, only retiring when Covid struck in early 2020.

“I liked what I was doing, so why should I retire?” he says. “I thought the natural cycle of life was birth, education, marriage, work, retirement, death, and if you broke the chain, you would live forever. If I didn’t retire, the next stage wouldn’t find me. People have said there’s a flaw in this logic, but I’m blessed if I can see it.

“But when Covid came along, our two boys – Andrew and Tristan – said ‘you’re old and vulnerable, you’ll be dead in three weeks, you need to stay away’, so we did, and I found retirement wasn’t quite as bad as I thought it was going to be. I’ve got lots of things to do.”

There’s the house they’ve lived in for 40 years he admits to having neglected, the sheep farming with Elizabeth and, of course, the cars.

As to the future, Martin says that “youngest son has expressed interest in the Stratos and he thinks it’s his birthright”.

“Although presumably by that time there’ll be no petrol and you won’t be allowed to drive cars,” he adds.

So which of his cars means the most? “The only answer I can give is what Ferrari said about his cars – the next one,” he laughs. “I suppose there’s an emotional connection with the TVR, but I don’t really go in for emotional very much.”