"Whatever your scooter preference - the long, sleek slimness of the Lambretta or the relatively substantial, reliable and zippy Vespa profile - the same artist-designer can be credited with coming up with the scooter formula. It was the end of "

Scooter mania! Teenagers and the Freedom Principle

Teenagers and the step-through scooter have gone hand in hand since the post-war years.

Here's a fistful of waypoints on the way to scootermania

What does the scooter mean to you?

It depends of course on your perspective. For some, the small displacement, step through scooter (with a skirt) is redolent of mid-century modernism, evoking the smells of Soho coffee bars and the texture of mohair. For others, the scooter is about the punkish teenage pursuit of the freedom principle. In between and at each extremity it is of course about barely legal high voltage ped-heads buzzing in provincial city centres or the sensible super-commuter with long legs and a twist-and-go technology. Wherever you sit on the continuum, the scooter has seen an interesting evolution. Here are a fistful of important waypoints to the scooter’s ever-changing identity.

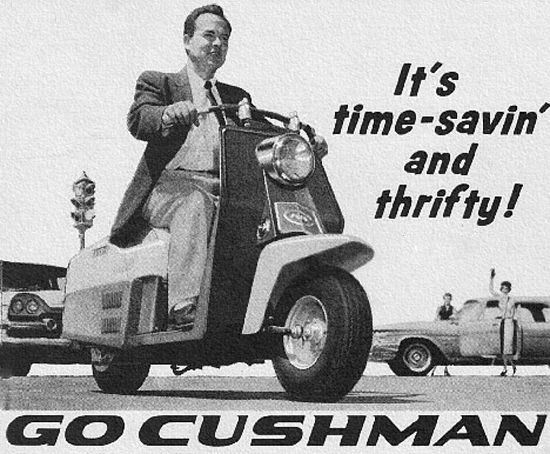

The Cushman

Cushman was a Nebraska company that began trading at the turn of the 20th century. They manufactured all sorts of vehicles and equipment, but famously the model 53 scooter was designed to be dropped by parachute with Army Airborne troops. Many cite these ex-GI scoots as inspiration for the first Italian scooters. Late 1950s Cushmans had Jetson-style body styling. This is one of the earliest manifestations of transatlantic auto culture.

The Vespa Mk 1

Italian industrialist Enrico Piaggio had surveyed the ruins of post-war Italy and quickly realised that the population needed cheap transportation. His company already produced the MP 5 (nicknamed Paperino, the Italian name for Donald Duck because of its weird design,) but Piaggio had never been convinced of this bike’s qualities. He challenged designer Corradino D’Ascanio (more about Corradino here) to come up with a better product. For his part, D’Ascanio hated the motorcycle. He thought them bulky and unsafe. Worse still the drive chain alone made for an extremely dirty riding experience. To eliminate these problems D’Ascanio made sure that the rear wheel was driven directly by the engine, eliminating the need for an oily drive train. He put the gear lever on the handlebar and gave the vehicle a body that carried all the stress and created a seat which was far safer than that of the motorcycle. When Piaggio saw D’Ascanio’s original designs, he exclaimed, ‘Sembra una vespa!’ – It looks like a wasp!

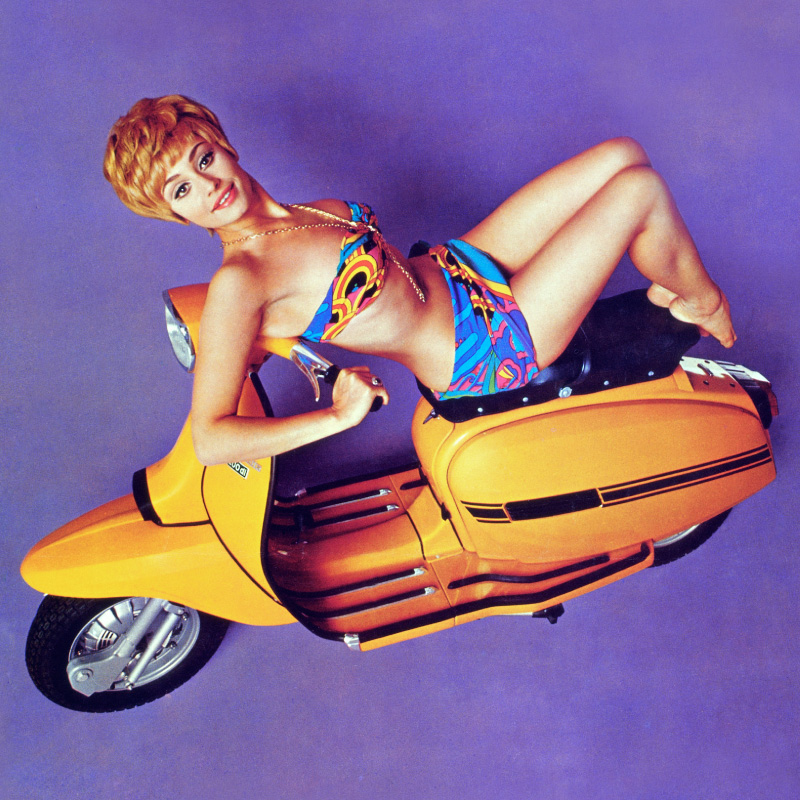

Lambretta Series 3 GP200

The GP200, an orange one of which is owned and ridden by Ally Barr in this month’s film, was one of the most desirable scooters of the late sixties and early seventies. In the UK and some other markets, the model was called the Gran Prix. This was due to the fact that in the late 1960s Formula One racing was at its heyday in the UK, with drivers such as Jackie Stewart big news, and Lambretta Concessionaires wanted to market the new model in a way to match its sporting looks. As Ally mentions, these bikes were the Ford Capri of the scooter world. That sleek bodywork with the colourful steel offset by matte black plastic touches was penned by the house of Bertone, after all. The series 3 came also with front disc brakes and dampers too.

Quadrophenia

The Mod revival was already moving on apace in the late seventies when the Quadrophenia film went into production. But when it hit the cinemas of Britain that revival exploded. The film, directed by Frank Roddam owed much of its success to that brilliant art direction, the costumes and the scooters. It didn’t exactly reflect the folk memory of the sixties Mod thing. It came with a psychedelic, introspective score by a spaced-out Pete Townsend and The Who. To this day, we don’t really understand the association of the sound of late-seventies The Who and Mod culture. But no matter. The film was shot through with just the right amount of youth cultural cues to get kids inspired. There was alienation. There was rebellion. There were working class kids dressed to the nines in the search for a cool kind of freedom. It touched a nerve and was a catalyst. Knee-tremblers in seaside alleyways, riotous dance floor scenes and of course mass scooter road trips and beach battles with greasers made us all want to get involved.

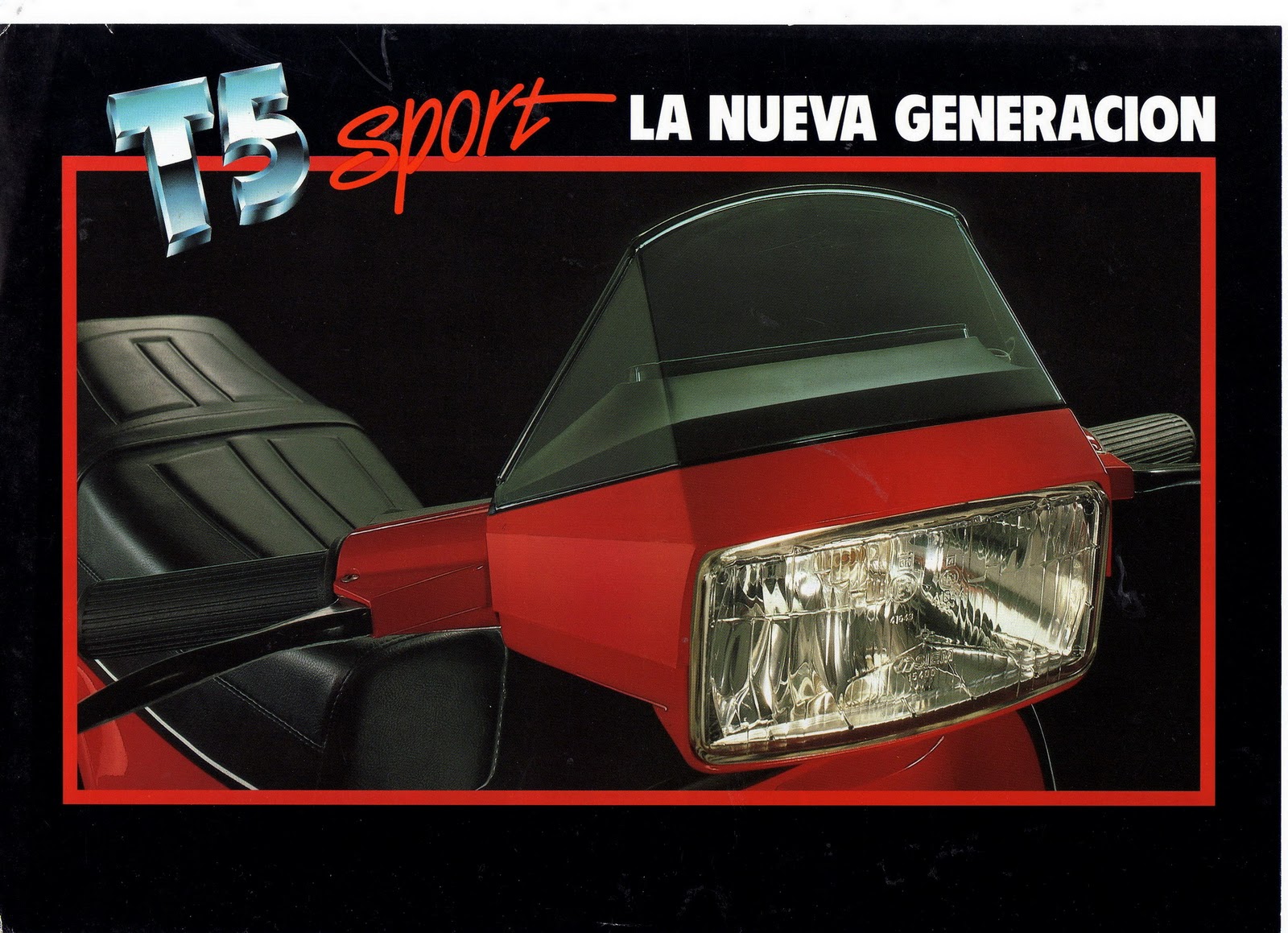

Vespa T5

As Andy Gillard explains to us this month, Vespa’s jarring mid-eighties release alienated many Quadrophenia-reared traditionalist scooterists. But if the scooter was all about nippiness, simplicity and fun, then it’s hard to argue that the introduction of a five-ported power unit was an inspired idea from Piaggio. A square front lamp coupled with boxy panels and that bulbous rear light made the T5 stick out from the crowd – and in a battle with wannabe greaser on a Fizzie there was no contest away from the lights.

London Bikelife

Whether they are underground superstars of the street, networked as they are to the nth degree across social media – or just a teenage menace, ‘pedheads’, as scooterists these days are sometimes known – are once again a visible cult on the streets of the UK. The traditional styling threads are replaced with trackies, Reeboks, diamond studs and man bags, but there’s no doubt that it’s a burgeoning, vibrant scene. When Vice launched this mini doc in 2014 the scene went (slightly) overground – but groups like the London Rise Up and UK Bike Life communicate on social and operate more or less below-the-radar, having a ton of fun and creating their own unique identity.

Just as every youth cult should.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Is that “2 Seasons” Ally?