" Still reeling from the breathtaking beauty of the McLaren display at the recent Autosport Show, we couldn't help but share with you this delectable pic of the cockpit of McLaren's 1989 successor to the all-conquering MP4/4. We're not sure wether this "

Alain Prost: the Other Edge of Genius?

Faster than his ultra-smooth style would have you believe...

To many modern Formula One fans, the current crop of turbocharged cars are the work of the devil. They’re too quiet, too driver-friendly, too reliable and even, some say, too safe.

But it wasn’t always thus. Time was when turbocharged Formula One cars were fire-spitting monsters with engines that were both spectacularly powerful – by 1986 the best of them could pump out as much as 1500 bhp in qualifying trim – and spectacularly fragile, with a prodigious talent for self-immolation. They were brutes to drive in other ways too, with suspension that existed in name only and controls that even Charles Atlas might have found a touch on the heavy side. And to cap it all, they were designed with what, to 21st century eyes, might appear to be a somewhat laissez-faire attitude to driver safety.

It’s therefore surely no coincidence that some of the greatest drivers ever to grace the sport – Gilles Villeneuve, Ayrton Senna, Nelson Piquet, Nigel Mansell and Niki Lauda – competed in that era. But even in such company, the history books show that one man stood above all others.

Consider this: the man in question won thirty-five Grands Prix at the wheel of the first generation of turbocharged cars, more than twice as many as any other driver. Consider this too: he was the first man to beat Jackie Stewart’s mark of 27 Grand Prix victories, the first to score a half century of wins and the only man to beat Ayrton Senna over a Formula One season in identical cars. Indeed, he actually scored more points than Senna in both of the seasons that they raced together.

Later on he led his own Grand Prix team and even found time to win the Andros Trophy on three occasions. No ordinary man, then.

And yet he’s seldom mentioned in the same breath as Senna, Schumacher, Clark or Fangio. It’s an enduring mystery, one that we’ll now explore by taking a brief look at the life and fast times of Alain Marie Pascal Prost.

Born in February, 1955, the young Prost aspired to become a footballer or sports instructor. And the chances are that he’d have done just that had he and his brother not chanced upon a seaside go-kart track on a family holiday. For Alain, then in his early teens, that brief experience was a ‘sliding doors’ moment, one that ignited a hitherto dormant passion for motorsport.

Like most drivers of that era, he had to serve a long and hard apprenticeship in junior formulae before being admitted to the fraternity of Grand Prix drivers. Having won championships in karting and Formula Renault his big break came in 1979, when he dominated the European F3 championship at the wheel of a Martini-Renault Mk 27, scoring more than twice the number of points as his nearest rival. He also won the highly prestigious Monaco F3 race that supported the Grand Prix – the perfect way in which to make a good impression on the watching Formula One team principals.

Those successes led to an offer to drive for McLaren in the season-ending US (East) Grand Prix. Prost politely declined that invitation, but happily accepted an offer to test for the team at the Paul Ricard circuit in the close season. In spite of his lack of experience behind the wheel of a Formula One car and his unfamiliarity with the McLaren, he set a quicker time than John Watson, the team’s regular driver. Legend has it that McLaren team principal Teddy Mayer watched Prost for all of ten laps before dashing to his car to retrieve a contract for him to sign.

Prost’s stay at McLaren would, however, be a short one. He made a promising start, immediately outpacing Watson and scoring points in each of his first two Grands Prix. The McLaren M29 was, however, no match for the best of the competition, a fact highlighted by Watson’s failure to qualify at Monaco. So with four races to go, McLaren rolled out a new car, the M30. Only one chassis was built and the team entrusted the job of driving it to Prost. It would be the last McLaren to appear before the team’s merger with Project 4 Racing heralded in the Ron Dennis era, but it failed to revive the team’s fortunes. Indeed, it turned out to be inferior to even the venerable M29, and though Prost managed to score a point on its debut he invariably found himself qualifying behind Watson. An accident at the season-ending US (East) Grand Prix put paid to both the M30 (though it was later rebuilt) and to Prost’s tenure with the team. Although McLaren had an option on his services for 1981, Renault were able to prise him away following some legal and financial wrangling.

At Renault in 1981, Prost was paired with fellow Frenchman René Arnoux, regarded by many as the fastest man in Formula One over a single lap. But although René scored four poles to Alain’s two, Prost’s superior racecraft saw him outshine his more experienced team-mate, winning three Grands Prix and leading more laps than any other driver en route to a very competitive fifth in the championship.

The 1982 season turned out to be most turbulent – and one of the most tragic – in Grand Prix history. It kicked off with the drivers going on strike, followed quickly by heated wrangling over a wheeze devised by Cosworth-powered teams to enable their cars to race well under the legal minimum weight, and culminated in most of the UK-based teams boycotting the San Marino Grand Prix.

For Prost, it started with a win on the track followed by one delivered by an FIA Tribunal. But that was as good as it got. For the second year running he led more laps than any other driver without coming within touching distance of the championship, thanks largely to the Renault engine’s propensity for self-destruction.

The championship would elude him yet again in 1983, in spite of winning four Grands Prix and utterly dominating new team-mate Eddie Cheever. Having led the championship table for much of the season, Prost could only muster a single points-scoring finish in the last four races, thus enabling Brabham’s Nelson Piquet to overhaul him at the season-ending South African Grand Prix. With Prost and Renault blaming each other for missing out on the championship, a parting of the ways was inevitable. The upshot was that the Régie showed Prost the door, temporarily leaving him without a drive for 1984. And if that wasn’t bad enough, some disgruntled Renault employees allegedly vented their feelings towards Prost rather more bluntly – by setting fire to his road car!

But as one door slammed shut, another one opened. McLaren, who had been gradually recovering from the nadir of the 1979 and 1980 seasons, moved quickly to re-sign their former driver. It turned out to be an inspired move for both parties.

McLaren had three aces in the hole for 1984: TAG-branded Porsche engines, the design skills of John Barnard and, in Prost and double world champion Niki Lauda, the strongest driver line-up on the grid. The combination proved to be a winning one and the championship battle came down to a straight fight between the hungry young Frenchman and the steady, assured Austrian veteran. It was a fascinating battle, one in which Prost won the most races and led the most laps of anyone but lost out to his wily team-mate by half a point at season’s end.

Unsurprisingly, McLaren fielded the same line-up in 1985. This time, however, it was Prost who emerged as world champion, and by a considerable margin. A year spent observing Lauda at close quarters had augmented Prost’s already formidable arsenal, and he made the most of it. The country that had pioneered Grand Prix motor racing finally had its own Formula One champion. And it had been achieved in a car that, though fast, was not the dominant force that its predecessor had been in 1984.

With Lauda having retired at the end of the 1985 season, Prost faced up to the challenge of racing alongside another world champion in 1986, Keke Rosberg. Some observers reckoned Rosberg to be the fastest man in Formula One and a mouthwatering clash looked to be on the cards. And that’s exactly what happened, albeit the challenge came not from Rosberg but from the Williams of Mansell and Piquet. Although Prost’s McLaren lacked the outright speed of the powerful Honda-powered Williams, his racecraft and guile, couple with a thick slice of ill luck for championship leader Mansell in the final race of the season, proved to be enough – just – to see him retain his championship.

It wouldn’t be sufficient, however, to bridge the gap to the dominant Williams-Hondas in 1987, Even so, Prost won three Grands Prix and take fourth in the championship, completely eclipsing yet another new team-mate, Stefan Johansson, along the way.

With new regulations on the way for 1989, the 1988 season would be the turbo’s swansong, at least for the 20th century. It would be one to remember.

Now powered by Honda, McLaren fielded the stunning new Steve Nicholls/Gordon Murray penned MP4/4. They had a new driver too: Prost being paired with the fast, hyperfocused Brazilian, Ayrton Senna. The new McLaren line-up reminded some people of the Prost-Lauda pairing, only this time it was Alain who would play the part of the older, more seasoned double champion.

From the start Senna was determined to make his mark. He took pole position for thirteen of the sixteen races, winning eight of them. Prost adopted a more measured approach, taking pole on only two occasions but leading the field home seven times. It would have been 1984 all over again, with the young hotshoe being bested by the wilier, more experienced campaigner, but for a scoring system that meant that only a driver’s best 11 scores would count towards the championship. Prost scored a total of 105 points that season, 11 more than Senna. But whereas Prost had to drop 18 of those points, Senna had to drop just four, making him the champion by three points.

Prost and Senna had managed to make it through 1988 without any major disagreements, but 1989 would be a different matter.

Having locked out the front row at Imola, in the season’s second race, Senna and Prost agreed that neither would race the other until after they had negotiated the sharp left-hand Tosa bend. Senna made the best getaway at the start, only for the race to be red-flagged due to a violent accident involving Gerhard Berger’s Ferrari. At the subsequent re-start, Prost made the better start and led the field down to Tosa. Believing that Senna would not – as per the agreement – try to pass him, Prost made no attempt to cover the inside line. Senna, however, had other ideas, and passed Prost under braking. An infuriated Prost was angered still further by Senna’s post-race claim that their agreement had only applied to the the first start.

McLaren principal Ron Dennis extracted an apology of sorts from Senna. The damage was done, however, and the situation was further inflamed when some injudicious comments made by Prost about Senna ended up in the pages of L’Equipe.

The fall-out from Imola also marked the beginning of the end of Prost’s relationship with McLaren. By mid-season, with the battle for the title in full swing, he announced that he would leave McLaren at the end of the season for a new destination: Ferrari.

First, though, there was a title to regain. There was further controversy at Monza, where Prost threw his race winner’s trophy to the crowd, infuriating Ron Dennis. But that was the least of it. Senna had outqualified Prost by 1.8 seconds, much to the latter’s bemusement. When Prost suggested that Senna’s huge advantage in qualifying was engine-related, an outraged Honda informed McLaren that they would refuse to supply any more engines to Prost unless he apologised. Backed into a corner, Prost had no option but to say sorry.

By the time the Grand Prix circus reached Suzuka, Prost’s steady approach ensured that he had a 16 point lead over Senna (in actuality, he had scored 21 points more than Senna but had to drop five of them under the scoring system).. This meant that Senna had to win the last two races of the season in order to retain his title. But with six laps to go at Suzuka, he was running second to Prost. The echoes of what happened next would linger for a long time.

As the two McLarens approached the chicane that led to the pit straight, Senna made a desperate attempt to pass Prost at the chicane, lunging down the inside from a long way back. He expected Prost to make way for him, but this time Prost refused to do so, with the result that the two cars collided at low speed. Prost clambered out of his car, but Senna got going again with the help of marshals. After pitting for a new nose, he reeled in the new race leader, Alessandro Nannini, and took the chequered flag. However, the stewards decreed that Senna had broken the rules by receiving outside assistance. He was therefore disqualified, handing the race to Nannini and the championship to Prost. McLaren lodged an appeal but the result stood. Worse still for Senna, he was labelled a ‘dangerous driver’ by the FIA, fined $100,000 and given a suspended six-month driving ban. That he took it badly hardly needs to be stated.

But if the 1989 Japanese Grand Prix was controversial, the following year’s event eclipsed it in spectacular fashion. Prost and his Ferrari had given Senna and McLaren a good run for their money throughout the 1990 season, and only nine points separated championship leader Senna from his former team-mate with two races to go. The two men duly lined up side by side at Suzuka, but pole-sitter Senna was furious on learning that he’d have to start from the dirty side of the track. As had happened the previous year, Prost made the better start and led into the first corner with Senna in close attendance. The Brazilian, still seething at perceived injustices, dived down the inside of Prost, going for a gap that didn’t exist. His offside front wheel made contact with Prost’s nearside rear wheel and the two cars spun off the circuit at over 140mph. With both drivers out of the race, the championship went to Senna.

Prost was livid, reasoning that Senna had been grossly irresponsible. Most neutral observers sided with Prost, a viewpoint that was vindicated when Senna admitted a year later that his actions had been deliberate.

Prost remained at Ferrari for the 1991 season, but the Scuderia was unable to supply a car capable of winning races let alone challenging for the title. A difficult season ended early for Prost, who was sacked by Ferrari with a Grand Prix still to go after referring to his car as ‘a truck’.

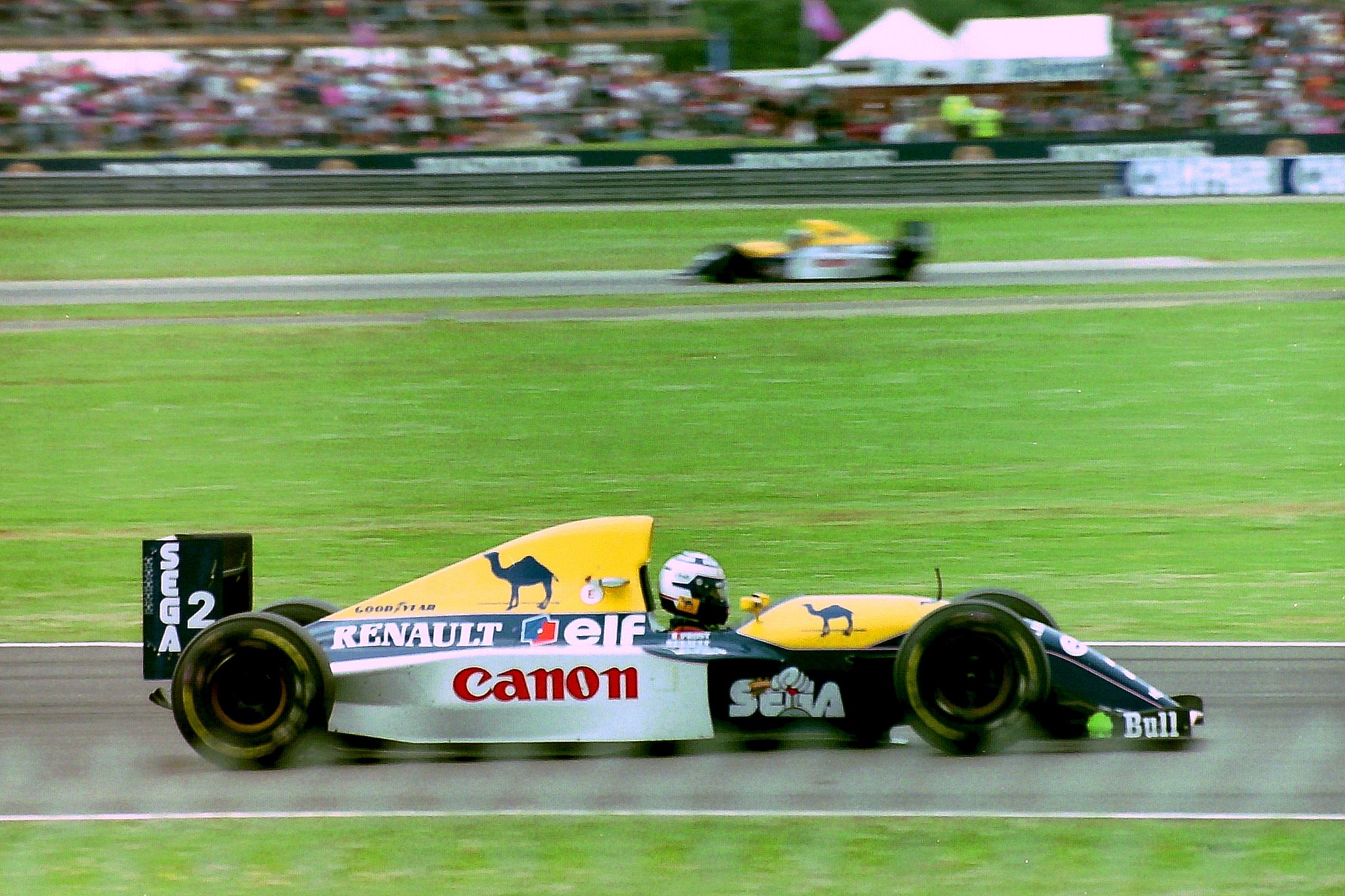

With no competitive seats available for 1992, Prost took a sabbatical. He returned in 1993, effectively replacing the reigning world champion, Nigel Mansell, at the Williams-Renault team. Such was the dominance of his steed that Prost took the championship by a margin of over 25 points without ever seeming to approach the level of performance that had once been second nature to him.

It wasn’t all sweetness and light, though. Aware that Senna was out of contract at the end of the season, Williams wanted to sign him for 1994. But there was a stumbling block: Prost’s contract, which had another season to run, expressly prohibited them from doing so. Unwilling to face another season like 1989 and keenly aware that professional sport places little value on the sanctity of a contract, Prost reached a deal with the team. Senna would join Williams and he would retire. And this time, after four championships and 51 Grand Prix victories, it would be for good.

Following his retirement from Formula One, Prost found to his surprise that Senna had not only obtained his phone number but was calling him on a regular basis. But a bigger surprise was in store: Senna told Prost that he didn’t want him to retire. Prost, however, was resolute, but he welcomed the calls and the chance they offered to rebuild his broken relationship with Senna. But just as it seemed that a friendship was being forged, Senna crashed fatally at Imola. Prost, who had spent some time with Senna on the morning of that fateful race, attended his former rival’s funeral in Brazil and helped to carry his coffin.

Prost never raced in Formula One again but he returned as a team principal in 1997, having purchased the Ligier team. That first season promised much, with Olivier Panis showing good early-season pace and Jarno Trulli leading the Austrian Grand Prix for a time. But that was as good as it got and the team, having entered into an expensive engine contract with Ferrari, folded at the end of the 2001 season.

It didn’t mark the end of Prost’s involvement with motorsport, though. Having had his fingers burned a little as a team owner, he picked up his crash helmet and went racing again. And a decade and a half after he’d left Formula One, Le Professeur was once more the proud owner of a championship trophy. This time it was the Andros Trophy, awarded to the winner of France’s ice racing championship. He would retain the title the following year and would reclaim it in 2013, at almost 58 years of age.

Now 63, Prost is still actively involved in motorsport, being both the senior team manager of the Renault e.dams Formule E team, for whom his son Nicolas drives, and special adviser to the Renault Formula One team.

That’s a supremely impressive CV by any measure, one which makes it all the harder to understand why he is seldom given the respect that his achievements merit?

Part of the answer to that might lie in the way he drove. Prost was never a spectacular driver in the mould of a Gilles Villeneuve, Rindt or Senna. His ultra-smooth style masked the speed at which he was driving, and it’s been said that only the stopwatch could easily tell the difference between Prost on a warm-up lap and Prost on a hot lap. It didn’t help either that he was a man not given to flamboyant or extrovert behaviour. A polite, refined individual, he didn’t make for colourful copy.

But there’s more to it than just a matter of style. There are some who denigrate Prost because of his disdain for racing in very wet conditions. But those same critics never experienced the horror that Prost did in practice for the 1982 German Grand Prix, when Ferrari driver Didier Pironi, unable to see Prost’s car through the spray, hurtled into the back of the number 15 Renault, taking off and thereafter somersaulting along the unyielding tarmac. Prost went to Pironi’s aid that day and witnessed the horrific, career-ending injuries to his compatriot’s legs. That he thereafter disliked extreme conditions owed nothing to a lack of bravery– no man who drove the powerful but flimsy cars of that era was anything but brave – but everything to a sober realisation that some risks are just not worth taking. In that respect, he was ahead of the game – it would take Formula One a long time to reach a similar understanding.

And then there’s Senna. To some, Prost lives in Senna’s shadow. But that, too, is a flawed view. When Prost and Senna became team-mates they were, like Prost and Lauda before them, at different stages of their career. In both cases, the older man, with championships in the bank and less to prove, simply took a different, more measured approach than his younger, hungrier team-mate. It was a question of maturity, not ability. And in the last few months of his cruelly curtailed life, it seems that Senna had started to ask himself many of the same questions that Lauda and Prost had once silently contemplated.

So where exactly does Alain Prost belong on the ziggurat of Formula One drivers? I rather think we’ve just answered that one…

header image credit: Mark McCardle

CLICK TO ENLARGE