The launch of the Triumph Dolomite was held up by strikes at British Leyland (BL), but when it did finally appear – months behind schedule in 1972 – it was to great acclaim.

A year later, the high-performance Sprint version took direct aim at BMW and Alfa Romeo.

Here was a British small sports saloon that could compete with the best in Europe – at a bargain price.

We look at the Dolomite’s intriguing history.

The Triumph Dolomite development story begins way back in 1962 when the company launched ‘Project Ajax’, an intended replacement for the Triumph Herald.

This was the Michelotti-designed Triumph 1300, the company’s first front wheel drive car using the engine from the Spitfire.

Rather than replace the Herald – which had enjoyed a sales resurgence – the 1300 appeared alongside it when it was launched in 1965.

It was, in effect, a scaled down Triumph 2000, and won plaudits for its high levels of equipment and good road manners.

A more upmarket 1300TC version was launched in 1967, while the facelifted Triumph 1500 – with the upsized Spitfire engine – arrived in 1970.

This had a more aggressive four-headlamp front end, and a longer boot, with a new dashboard updating the interior.

In the same year, a cheaper version – the Triumph Toledo – was born, with a very similar look to the 1500 but with single, rectangular headlamps and a shorter, 1300-style, rear end.

The Toledo, with its pared down specification, became the car aimed at Herald owners looking to trade up to a new car.

Crucially for the future Dolomite, it reverted to rear-wheel-drive and a live rear axle, a seemingly retrograde step at the time with front-wheel-drive all the rage.

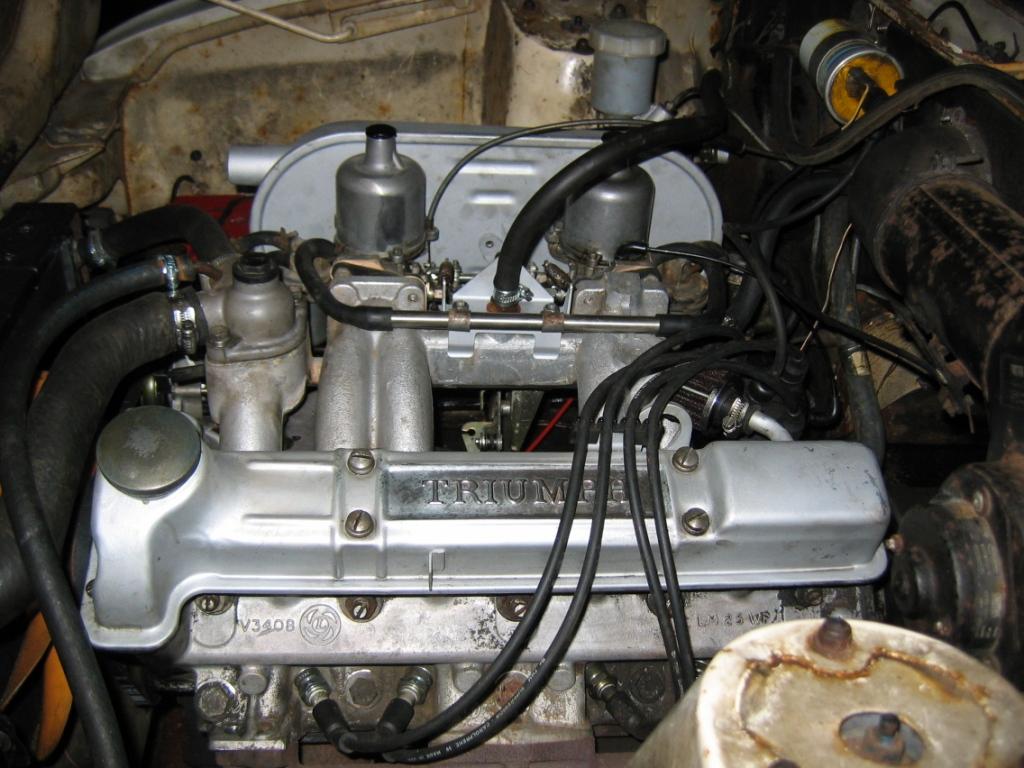

The Triumph slant-four engine

The range had always benefited from smart looks for the time, and buyers were left wondering if they could have some power to go with them.

Handily, there was a ready-made way for Triumph to beef up the car.

Back in 1963, Triumph had worked on a design study of engine requirements for the 1970s, and Saab had shown an interest in a new slant-four unit for their upcoming new car, the 99.

The engine’s 45 degree angle allowed for a lower bonnet line, and Saab provided funding to get the new engine into production, initially in 1709cc form.

Saab’s 99 was duly launched with the Triumph-derived engine in 1968 and, after the Swedish company’s exclusivity period was over, BL set to work developing the unit for use in their own cars.

The British company had the benefit of four years experience of seeing how the engine performed in the Saab – which was pretty well, given 75,000 99s were sold between 1968 and 1972.

Its canted design also allowed it to be easily transformed into a V8, as seen in the Triumph Stag.

Triumph Dolomite engineering

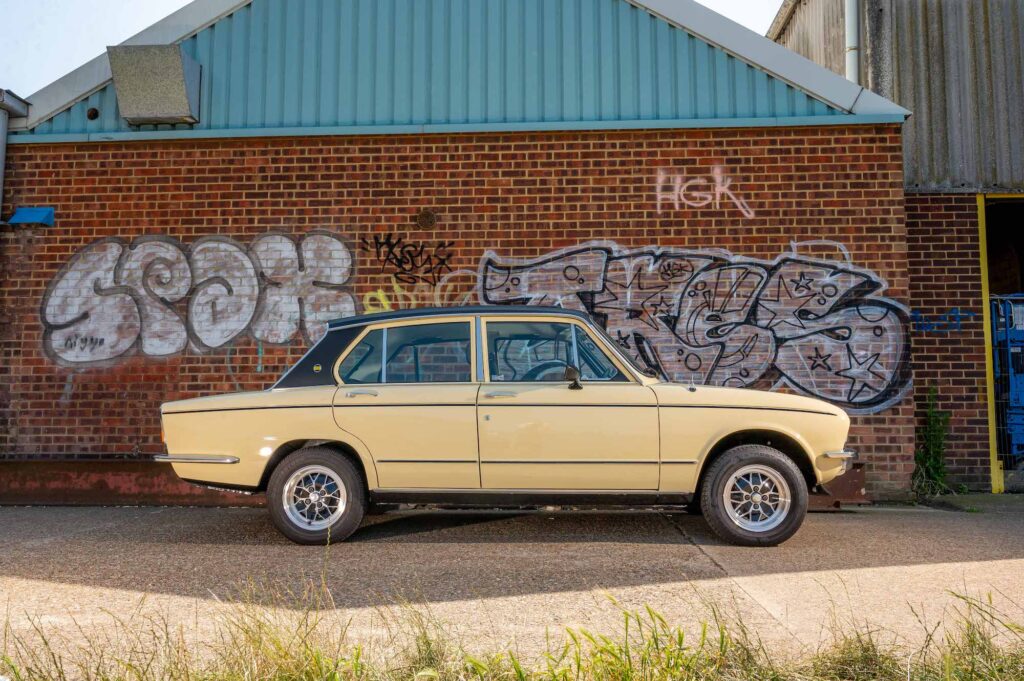

Under the guidance of Spen King, the new engine was shoehorned into the existing, longer, bodyshell of the 1500, and the Triumph Dolomite was born, reviving a pre-war name to differentiate it from the existing models.

For the Dolomite, the slant-four was bored out to 1854cc and, powered by twin Stromberg carbs, raised output from the 80bhp in the Saab to 91bhp, with a useful increase in torque from 99.6lb ft to 105lb ft at 3,500rpm.

So the new car was, effectively, an amalgamation of four others: an embellished version of the 1500’s body, the driveline and basic suspension of the Toledo, the high-quality interior appointments of the larger 2.5PI, and the beefed up Saab’s engine.

Motor magazine noted that there “is little entirely new about the new Triumph Dolomite”.

“But you would be woefully wrong to think that the car is not new or exciting; the result adds up to something quite different to any existing models in the Triumph range – or, indeed, to anything else built in Britain.

Adrian Flux Classic Car Insurance

“It is a new high-performance luxury model in its own right.”

Triumph’s small car range would now comprise the budget Toledo, with its short tail and rear-wheel-drive; the long-tailed, front-wheel drive 1500; and the long-tailed, rear-wheel-drive Dolomite.

Dolomite’s delayed arrival

Triumph bosses were keen to get the Dolomite into production as quickly as possible, but a pay dispute not only disrupted production plans but also prevented BL from fixing a price for the car.

The company wanted to get the new car into showrooms in 1971, but strikes at the Canley and Speke plants ensured that Triumph could not build up enough stock to start selling the car until the following year.

Thus, magazine editors who had carried out road tests in the anticipation of a September ‘71 release had to shelve them for several months.

By January ‘72, the pricing issue had been resolved, with Triumph’s answer to the compact luxury saloons from the likes of BMW and Alfa Romeo undercutting them by some way with a ticket of £1,399.

Motor could scarcely contain its enthusiasm for Britain’s new contender, describing the amalgamation of different cars into one “astonishingly successful”.

“There’s no other British car quite like it, the combination of performance, luxury, refinement and driver appeal calling to mind some of the (more expensive) wares of BMW, Alfa Romeo, Fiat and indeed Saab, rather than of Ford, Vauxhall or British Leyland,” it wrote.

“This, in fact, is exactly the market that Triumph are aiming at. It was the Dolomite’s overall excellence, judged by such international standards, that endeared it to all who drove it.”

Its low price made it “excellent value”, and the “outstanding engine” provided smooth motoring, excellent low-speed torque, and respectable performance – 100mph top speed and 0-60mph in 11.3 seconds.

The interior didn’t disappoint, with “a high standard of comfort and one of the best planned interiors we can recall”.

“The seats are excellent, the number of driving positions almost infinite, the switchgear superb, the furnishings, trim and equipment decidedly lavish.

The layout of the controls and the range of seat adjustment are an object lesson to all other manufacturers. Neither is equalled, even approached, at the price by any rival British or Continental car.”

CAR magazine tested the Dolomite against the Renault 16TS, and ended up plumping for the “small, nippy and more manoeuvrable” Triumph.

“How pleasant to be able to say that about a British car,” it concluded.

Triumph Dolomite Sprint development

By now, Triumph’s place within BL had become clear – they were to leave the larger car market to Jaguar and Rover, and focus on the group’s smaller cars.

So the Dolomite had become absolutely crucial to the marque’s fortunes, and Spen King set to work on taking things up a notch.

For while the basic Dolomite had sold well, it lagged behind the BMW 2002 on performance, if not on comfort and equipment.

Giving the slant-four more power would help the car compete better on the road and in motorsport, landing it more prestige against its Continental competitors.

King enlisted help from Harry Mundy and engineers at Coventry Climax to design a 16-valve, light alloy cylinder head to sit on a bored-out, 1998cc version of the engine.

The 16 valves, disposed in opposed pairs, were actuated by a single overhead camshaft driven by a duplex chain.

The intake valves were actuated via bucket-type tappets and, ingeniously, the same cam lobes served to actuate the opposite exhaust valves via non-adjustable rockers.

It provided the benefits of a multi-valve layout without the need for a second camshaft, and the unit was notable for being the first mass-produced, four-cylinder multi-valve engine.

The engine was fed by twin SU HS6 carbs, with peak output up massively to 127bhp at 5,700rpm, and torque likewise up to 124lb ft at 4,500rpm.

Transmission was provided by the Stag’s gearbox, while the rear axle was based on that of the TR6, which also lent its rear brakes, powered by a larger servo.

In styling terms, the existing body was embellished with a vinyl roof, a matt black rear tail section, coach lines along the sides, a beard-type spoiler, plus GKN alloy wheels as standard.

Inside there was a luxury, deep-pile carpet, Bri-Nylon broadcord seats, and wooden dash with a vast range of dials.

Arrival of the Sprint

When it finally arrived in the autumn of 1973, after the obligatory BL delays, the Sprint was rapturously received.

Here was a British sports saloon that could hit up to 117mph and reach 0-60mph in just 8.7 seconds, and all for just £1,740.

Autocar wrote in July 1973: “Here is a car capable of meeting foreign competition head-on.”

With kerb weight only up 87lb, but with a 40% boost in power, “it is little wonder that performance is on an altogether different plane”, it added.

The Sprint trounced rivals including the Ford Escort RS1600, Fiat 132 Special, and BMW 2002 on acceleration and top speed, with only the fuel-injected 2002 Tii quicker to 60mph.

It “must be the answer to many people’s prayer,” said Autocar. “It is well appointed, compact, yet deceptively roomy. Performance is there in plenty, yet economy is good and the model’s manners quite impeccable.

“Most important of all, it is a tremendously satisfying car to drive. With all this available for less than £2,000, Triumph are following the Jaguar lead in offering unique value for money.”

What Car? reflected on what “seemed a rather sick joke when the makers claimed they had an Alfa and BMW beater when they announced the Sprint”.

“But there is little doubt that if it had a BMW, Fiat or Alfa badge, British snob motorists would be rushing to buy one.”

Meanwhile, CAR magazine pitted the Sprint against its Ford rival, the Escort RS1600, a car qith a very different character and heritage.

“As an everyday car, the Dolomite sprint wins hands down over the RS1600, for it has decent performance, fair comfort, satisfactorily low noise level and some of the worthwhile attributes of proper performance motoring,” it wrote. “On the other hand, the RS1600 is a pre-breakfast car in which to have enormous fun for short distances.”

From May 1975, previously optional extras like overdrive and tinted windows were included as standard, while the colour range had already been widened from the original ‘mimosa yellow’ only.

Dolomite fragility and range rationalisation

Sadly, it wasn’t long before reliability issues began to dog the Sprint’s complex 16-valve engine.

Dealership mechanics were perhaps not fully up to speed with the requirements of looking after the cars, while the turbulent economic environment engulfing BLMC saw cost-cutting and the quality of parts and build quality suffered.

Terry and Brenda Windsor’s experience of a Sprint in the late 1970s was not untypical – with cooling issues often at the forefront of the car’s issues.

Nevertheless, Dolomites of all types continued to sell pretty well and, in 1975, its name subsumed Triumph’s small car range in a sensible rationalisation, with all cars sharing the same basic body.

There was now a Dolomite 1300, 1500 and 1500HL, 1850HL, and Sprint, with all cars now rear-wheel-drive – quite a transformation given the range began in 1965 with the front-wheel-drive 1300.

By the end of the 1970s, the Dolomite was starting to look very dated, and earlier efforts to update the design had fallen flat.

Back in 1972, Michelotti drew up plans for a restyled car for future production, using the Dolomite’s underpinnings.

But this design for Triumph’s SD2 programme was scrapped in 1975 because of BL’s finances and the internal politics of competition between the conglomerate’s different marques, notably the Princess and ADO77, the similarly shelved Marina replacement.

The end of the Triumph Dolomite

As it turned out, the Dolomite would not truly be replaced, and was left to soldier on through the late 1970s until its demise in 1980.

Towards the end, the Dolomite SE attempted to give the car a sales boost with luxury trim including burr walnut dashboard and door cappings, grey velour seats and matching carpet.

The SEs were all painted black with full-length silver stripes, a front spoiler and Spitfire-style wheels.

Only 2,163 were built as sales of the ageing car declined.

By the time of the car’s demise in 1980, just over 204,000 Dolomites of all types had been sold, of which nearly 23,000 were Sprints.

It was replaced by the Anglo-Japanese Triumph Acclaim, a collaboration with Honda and, effectively, a rebadged Honda Ballade.

But while the Acclaim was a perfectly good car, the Sprint’s sporting essence, along with its innovative slant-four, 16-valve engine, had been lost.

When Acclaim production ended in 1984, its successor would be badged as a Rover.

After more than 60 years, the Triumph name would no longer appear on anything with four wheels.