When Jem Bowkett bought his Ford Model T in 1979, he couldn’t have imagined it would lead to a new career featuring film and TV roles alongside some of the world’s most famous actors.

But that’s what happened when he was spotted with the Ford in 1980 and asked if he would consider renting the car out for a film.

“Only if I can come along to make sure it doesn’t get ill-treated,” he said, sparking a decade-long association with Shepperton Studios, driving not only his car but assorted Rolls-Royces and Daimlers and working with a roll-call of movie royalty.

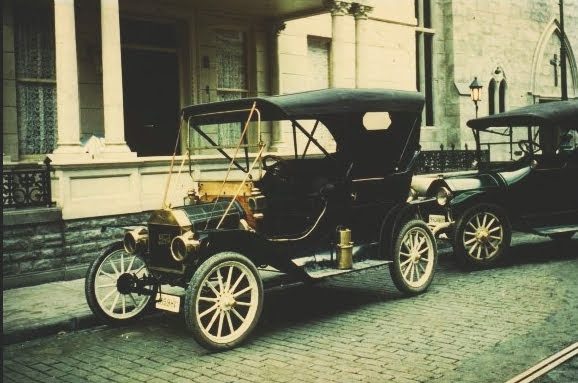

“A few months after that conversation I was on the back lot at Shepperton, standing six feet from Hollywood legend James Cagney who was starring in Ragtime,” he smiles, quitting his job in IT and working in the movies alongside dabbling in car restoration. The car is pictured here on set.

“It was good fun – you get to dress up and drive old cars and get paid for it. I played a German police driver chasing Roger Moore, and worked alongside people like Faye Dunaway, Julie Andrews, and Sean Connery.

“I have the distinction of being the last person to work with Richard Burton. I played his chauffeur in a TV mini series called Ellis Island in 1984, and we did a couple of clips in the morning where I’m driving a Rolls and he’s behind me giving instructions.

“In the afternoon he got on a plane, flew back to his home in Geneva and within about four days he’d died of a stroke.”

As well as opening a door to the stars, Jem’s Model T has carried him and his wife Linda all over the UK and into France through 44 years and at least 40,000 miles of idiosyncratic historic motoring.

A cursory glance at possibly the oldest Model T in the UK – car number 9267 and built on August 17, 1909 – reveals that this is no museum piece.

“That car’s got patina in bucketfuls,” he says, “it’s got history, and I didn’t even clean it for the first year.

“I rallied it ‘as found’, including the brass which was brown and crusty with corrosion. My best friend Willy Willson is a vehicle painter, and he said ‘I’ll paint it for you’, but I said ‘no, let’s leave it the way it is, everyone loves the way it looks’.

“At one point I was tempted to re-do the seats – they’re badly in need of changing. But I’ve got to the stage where I’m going to leave that to whoever inherits it from me.

“I suspect the next owner will decide to restore the car, which would probably be necessary if it’s going to be driven anymore. Otherwise, it’s a museum exhibit, and cars should be driven.”

Jem, 74, owes his love of pre-war cars to his brother Graham, seven years his senior, who started driving when he was 17.

“In those days if you were an impoverished student it was a pre-war car, so he had a couple or three boring things like a Hillman 14 and then one day a friend of his said ‘you keep nagging me to buy my car, you can have it for a fiver’,” he remembers. “He said ‘right, I’ll have it, thank you’. “‘Well, it was stolen last night, it’s in the duck pond.’ My brother went and got this 1937 Ford V8 Club Cabriolet out of the pond and I thought it was marvellous. Snorty V8 noises, it went like the wind, rag top, and I became obsessed with the Ford V8.

“When I started motoring, my first car was a 1938 Club Cabriolet in 1966. It was a bit of an eccentric thing but, if you think about it, it was only 30 years old, built before the war and fairly old technology, but there were still quite a few people driving round in secondhand pre war cars.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“Then I saw an advert in Exchange & Mart for a 1938 Ford Tourer for spares for £10. I went and looked at it hoping it was going to provide spares for my V8, and it was a Ford Prefect tourer, a very rare little car now – they only made 1,000 of them.

“I bought it for a tenner, towed it home and put a radiator in it because someone had stolen the radiator, and that was my daily transport for several years.”

A variety of Ford Populars and Model Ys followed before Jem, aided and abetted by Willy, got interested in Model Ts, the car that revolutionised motoring for the masses.

“I started buying bits and began building one from the chassis up,” he says, getting hold of an unused 1926 engine block. “But I then came into an inheritance and, after spending most of it on buying a better house, I still had some money in my pocket for toys.”

With Willy, he headed to the Hershey sales in Pennsylvania in 1979 and, having bagged a 1928 Ford Model A open cab pick up for $4,000 on the first day, they were attracted to a stand run by a father and son selling Ford Popular bits on day two.

“This fellow came out and said ‘oh you’re English, I was stationed in Suffolk during and just after the war, I don’t suppose you know Mrs Johnson my old landlady’,” says Jem. “Americans always do this – such a small country!

“It started raining so he said ‘come in the RV and we’ll chat’. We sat in the RV chatting, the ‘sipping Whisky’ came out and we were having a good time when this old boy, Dave, comes in and says to the son ‘Larry, the rain’s stopped, get the cover off that car’.

“We looked outside the window, he pulls off the cover and there’s this Model T on a transporter (pictured). I was looking at it and thought ‘that’s the earliest T I’ve ever seen’. I was instantly intrigued.”

They went outside, and Larry was instructed to start the car they had acquired from an estate sale.

“When Model Ts haven’t been driven for a long time, the multi-disc clutch gets absolutely gummed with oil and it’s really hard to turn it over,” says Jem. “Poor Larry is cranking away and the old boy is waggling the levers and saying ‘she kicked then, she’s about to go, she’s about to go’, until finally it fired up and Larry collapsed against the cab of the transporter, sweat pouring off him.

“I just thought ‘I’ve got to have this’.”

Jem paid $11,000 for the car and “that evening at dinner with our American friends I endured much ribbing – ‘Jem got drunk and bought a car!’”

The Model T, a matching numbers five-seater touring model, was taken back to Virginia, put into a container along with a load of spare parts, and shipped over to Felixstowe, where several months later Jem and Willy loaded it onto a trailer and brought it home to Berkshire.

“Remembering Larry’s troubles, I jacked up the rear wheel to ease things, cranked it up, and it leapt into life,” says Jem, not bad for a car that hadn’t been driven in earnest since 1962.

Henry Ford’s immortal refrain that ‘you could have any colour as long as it’s black’ didn’t actually kick in until 1915, which is why Jem’s car is green, the only colour on offer for late 1909 and 1910 cars.

“It had been restored in the 1950s and painted an unauthentic green and black, with hideous white wheels I’ve since painted in the correct Brewster Green,” he says, immediately putting the old car into service on road runs and rallies with the Model T Ford Register.

81.5% of customers could get a cheaper quote over the phone

Protect your car with tailor-made classic car insurance, including agreed value cover and discounts for limited mileage and owners club discounts

“When we first had the car, we packed all our camping gear on board and drove from Bracknell to Chesterfield, where we stayed overnight with the club president, Bruce Lilleker and his family, and then drove up in convoy to Morecambe where we did a club event,” says Jem. “We then spent the next week or so touring round the Lake District and Yorkshire.

“I remember descending a 4 in 1 hill in the Lakes (pictured) and, despite starting the steep descent at walking pace, I ended up with my feet spread across all three pedals and the handbrake on.

“With Linda preparing to bail out, we shot out onto a (luckily empty) main road at the bottom. Poor quality repro transmission bands were to blame.”

“We also had three punctures in as many miles on our way to the Wast Water campsite, caused by a protruding screw in the felloe, cured by duct tape.”

Jem and Linda embarked on many such trips in the ‘80s and ‘90s, including two rallies in Scotland, both in May.

“One was glorious summer weather driving around the Edinburgh area, and the other was ghastly – it rained and actually snowed,” he says, describing the T’s very effective heating system.

“It’s called the hole in the floorboards! In fact, in the summer the front passenger can find themselves riding with their feet outside the car. I’ve got a friend with a right hand drive T where the pedals get so hot he says if he wears rubber soled shoes, they stick to the pedals.

“If it is a vile day you put the top up and it’s amazing how much of that heat stays in.”

Over the years, the car has made two trips to France, once trailered down to the Loire (pictured camping), and once driven over to Normandy via the ferry.

“That’s when the fan belt fell off, so I crafted a new one from my trouser belt,” he says. “It works, so it’s still there.”

Naturally, with a car of such great age, and one that was still in its early stage of development when it was new, there have been some more serious mechanical issues.

“These cars evolved very quickly in the first few years,” says Jem, “and Ford’s test drivers were their customers, who were out there breaking cars and coming back saying ‘the back axle’s failed’ etc…

“We had the original back axle on the car when I got it, and that failed on us in a spectacular way.

“We’d been up to the All Ford Rally in Abingdon and we were coming home with four people on board.

“I stopped at a petrol station and a guy said ‘you know your car’s leaking oil’ and I thought ‘yeah, Model Ts do that, they just dribble oil’ so I didn’t think anything of it.

“But as we pulled into the driveway at home, the torque tube pulled out of the front of the axle, completely locked the back axle, and we jerked to a halt. We were all thrown forward, and I still have nightmares thinking what would have happened if we’d been doing 30mph when it failed.

“I replaced it with a 1920s back axle, by which time they’d found a design that didn’t break.”

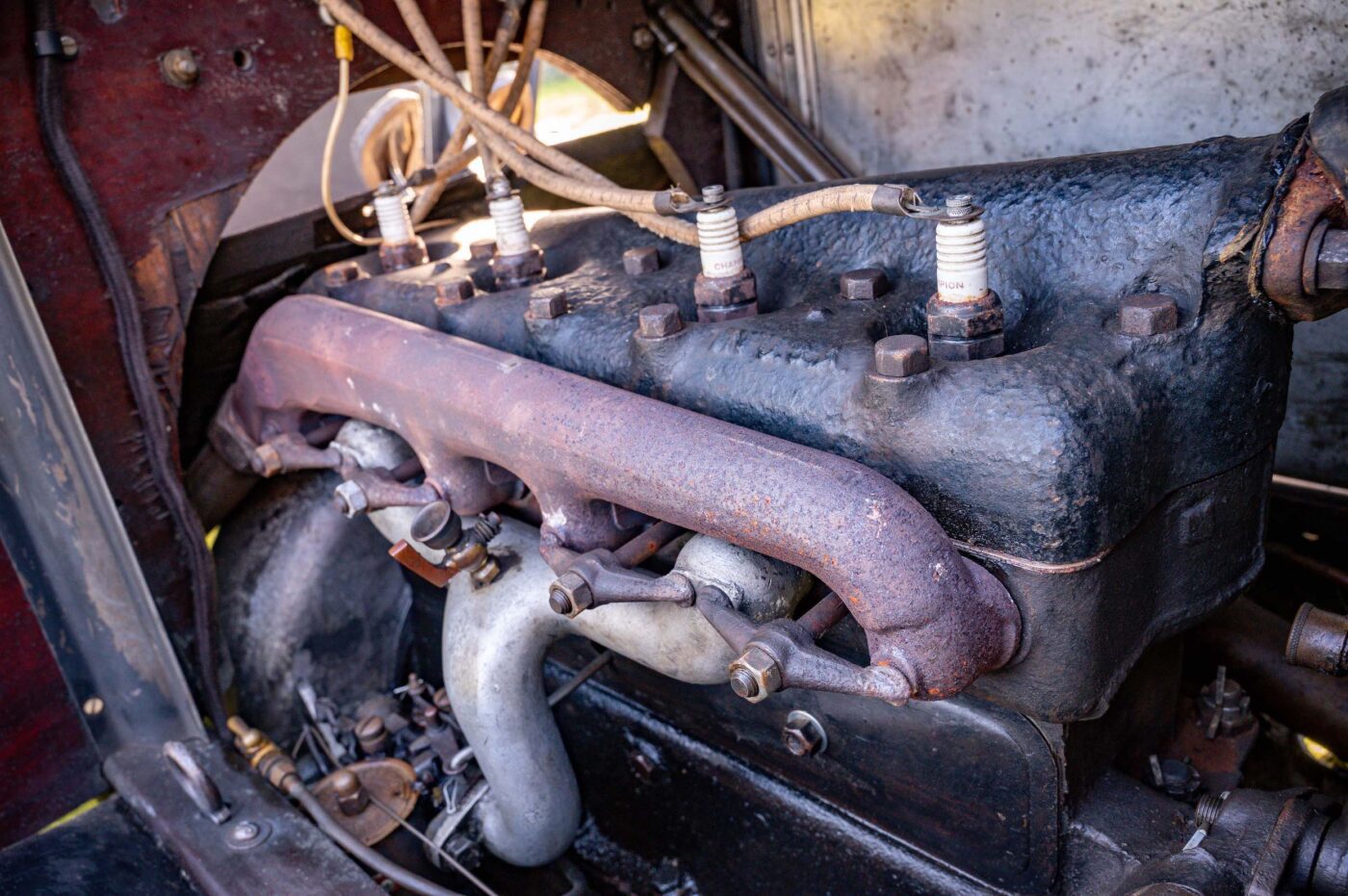

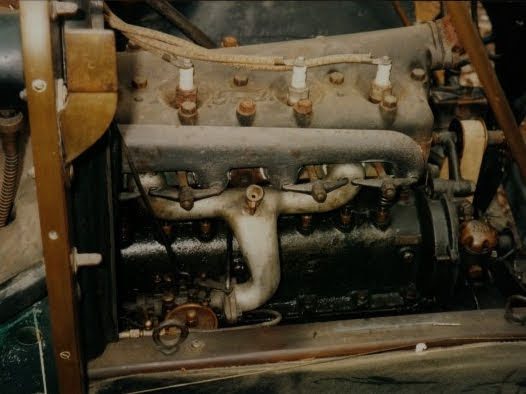

Jem drove the car for many miles on its original four cylinder, 2.9-litre engine (pictured), a unit which was refined and improved over the years by Ford’s engineers.

One of its issues, ironed out on later engines, was to bite Jem heading off to Stockbridge in Hampshire for the Daffodil Run.

“We came to a violent halt pulling up an incline at about 20mph,” he says. “The engine had locked solid because the crankshaft had snapped, tearing the rear main out of the block and slamming the flywheel into the magneto ring.

“The cast iron on that style of block is thinner than the later ones, and when I had to have it metal stitched back together the guy said it was really tricky to repair because it was so thin.

READ MORE ABOUT SOME OF OUR GREATEST CLASSIC CARS WITH

A series of articles on our Cult Classics site.

“But the reason it failed was because on the early cars they didn’t put any babbitt in the top half of the main bearing. It’s now babbitted and line bored, so it’s stronger. And instead of old cast iron pistons, it’s got modern aluminium pistons.”

Fortunately, Jem had the 1926 engine that he’d bought previously to hand, which has been in and out of the car whenever there’s been an issue with the original.

At the time of our visit, the later engine is in the car and engine number 9267 is once again in the workshop because of a problem with the magneto.

It provides a good opportunity to look at the inner workings of the side valve engine that drove a motoring revolution, with its built-in magneto, multi-disc clutch, constant mesh gears – two forward and one reverse – and, in early cars, exposed valves.

“Ford was trying to make a car that would do for people out in the country,” says Jem. “The previous cars they made had coil ignition with a battery, which was fine if you lived in town because you took it to your local radio shop and they charged your battery up.

“But this has a built-in magneto, so you get between 8 and 30 volts AC when the flywheel spins round, and that fires the ignition. It’s just a big alternator.

“When I first took that engine apart to look at it, it had two-and-half-thou oversized pistons, and that was what they used to do in the good old days if you’d worn the car out – hone it out and put in some oversized pistons.

“So that told you the car had done some miles. God knows how many thousands of miles that back axle had done before it gave up the ghost.”

And covering miles it’s what it’s all about for members of the Model T Register, which Jem says is “very driving orientated”.

“They are cars that people like to drive,” he adds. “I love driving Ts. Once you’ve got the knack of the strange controls, and that becomes second nature, they’re really nice to drive.

“It’s quite a comfortable car as long as you don’t hit a pothole, though you’re very high up and it’s a little like sitting in a horse drawn carriage.

“You’ve nothing to hang on to at all as a front seat passenger. One one occasion, we were coming back from an all-day event and Linda was just enjoying the view when some guy pulled alongside in a Ford Transit and went ‘toot, toot, toot’ right in her ear.

“She stood up and I had to grab her by the back of the neck and pull her back down again. You can easily fall out.

Jem and Linda’s days of longer-distance runs and adventurous camping trips are behind them, with a combination of the car’s fragility and modern traffic restricting them to rallies and shows closer to home.

“In the early days, we’d just go off camping in it, which I would hesitate to do now because, though it’s only 40 years ago, the traffic has changed considerably, and also the drivers have changed,” he says.

“Back then there were still a lot of people on the roads who had bought bangers and knew what bangers were like – their first car had been something that had probably only just managed to pass an MoT, so there were lots of cars around which had poor steering and brakes.

“But now people roar past you and if there’s a traffic light ahead they fill your braking space and put the brakes on. You’re thinking ‘where the hell do I go?’. This car has ABS – alleged braking system. So it’s not so much fun.”

We’re about to go for a short ride to our photoshoot location, but first Jem demonstrates exactly how you drive this ancient automobile, which has been likened to trying to pat your head with one hand while circling your stomach with the other.

After switching on the trembler ignition coils, he cranks over the engine with the starter handle and the car comes to life.

There are three floor-mounted pedals – the left controls the gears, low, high, and neutral; the middle is reverse gear; and the right is the transmission brake pedal.

With the engine running, depressing the left pedal puts the car into its low forward gear, releasing the pedal to its halfway point puts it in neutral, and letting it come all the way up puts you in high gear – where you can ride at up to 45mph controlled by an accelerator on the steering wheel.

“You have to learn to put the pedal halfway down for neutral, because when you first get a Model T and do an emergency stop, you tend to hit the brake and put it into low gear and you have to learn not to do that,” says Jem, showing us round one of two other curiosities for the modern driver, like the gradient meter and acetylene generator.

The gradient meter (pictured) lets the driver know if they are likely to get up a hill or not…

“This is only a two speed, and Low is very low while there’s a big hole to High, so if you can’t romp up a hill in top gear you’re down to walking pace,” he says. “The only Ford-approved aftermarket accessory you could buy was a two-speed back axle, which gave you an underdrive so you could have an intermediate gear.“Linda has a vivid memory of doing the Kop Hill Climb, completing most of the hill at walking pace in Low, with the Marshals deserting their straw bale defences to cheer us on.”

The acetylene generator (pictured), a brass cylinder on the side of the car, provides the power for the headlights via a reaction between calcium carbide and water.

“You put calcium carbide in the little basket inside, and water from a tank on top drips down onto it, causing a chemical reaction that produces acetylene gas, which travels along a pipe to the burner,” explains Jem.

“I wouldn’t say you can see a lot, but if you were driving it in 1909 conditions with everybody else having the same sort of light, and not the amount of street lighting and other rubbish we’ve got nowadays, they’d be perfectly good.

“Guys I know in the States who use them regularly say they’re fine, but the trouble is if somebody comes the other way with a set of halogens and suddenly you can’t see a thing.”

Pretty soon, with a few squeals of protest from the old car’s transmission, we’re gently bouncing along the less than even roads around Jem’s Lincolnshire home.

A lady in her front garden waves (Jem says he’s never seen her before), and a van driver waiting at a side road appears to make a breast stroke swimming gesture.

“It does get a lot of attention,” says Jem. “We go to classic car shows these days, where the guideline is 15 years old or more, and I look around and think I’m in Tesco car park.

“So when you turn up in something that really is veteran, it turns heads.”

Jem admits there’s an emotional attachment to a car that has given him so much pleasure for so many years.

“I suppose so, it’s been glued to my arse for 40 years,” he laughs. “It would be difficult to let it go. We’re just going to enjoy taking it to local shows, but there will come a point at which I will say ‘I’m not going to be driving cars anymore’, and I shall have to sell.

“I don’t want to hang on to it while I go gaga in a care home and have it become a neglected barn find estate sale again.”