"To run the risk of sounding a little bit like Prof. Brian Cox here, Josse was the briefest of flashes in our galaxy of motoring. Unless you happened to be looking in the right place at the right time, you "

AC 3000 ME: The Best Laid Schemes – Classic Car

Right car, wrong time?

“The best laid schemes of mice and men gang oft agley and leave us nought but grief and pain for promised joys.”

Those words, written by Robert Burns in 1785, might be said by some to describe the saga of the AC 3000 ME, the last car built by the iconic marque at its long-time Thames Ditton home.

But do they? Let’s look at the evidence.

The ME’s story began when Peter Bohanna, an industrial designer late of Ford Advanced Vehicles, Alan Mann Racing and Lola, joined forces with Robin Stables, a development engineer who had worked on road and racing cars throughout Europe. Combining their talents as Bohanna-Stables (they later dropped the hyphen), they designed and built a pretty mid-engined sports car: the Diablo.

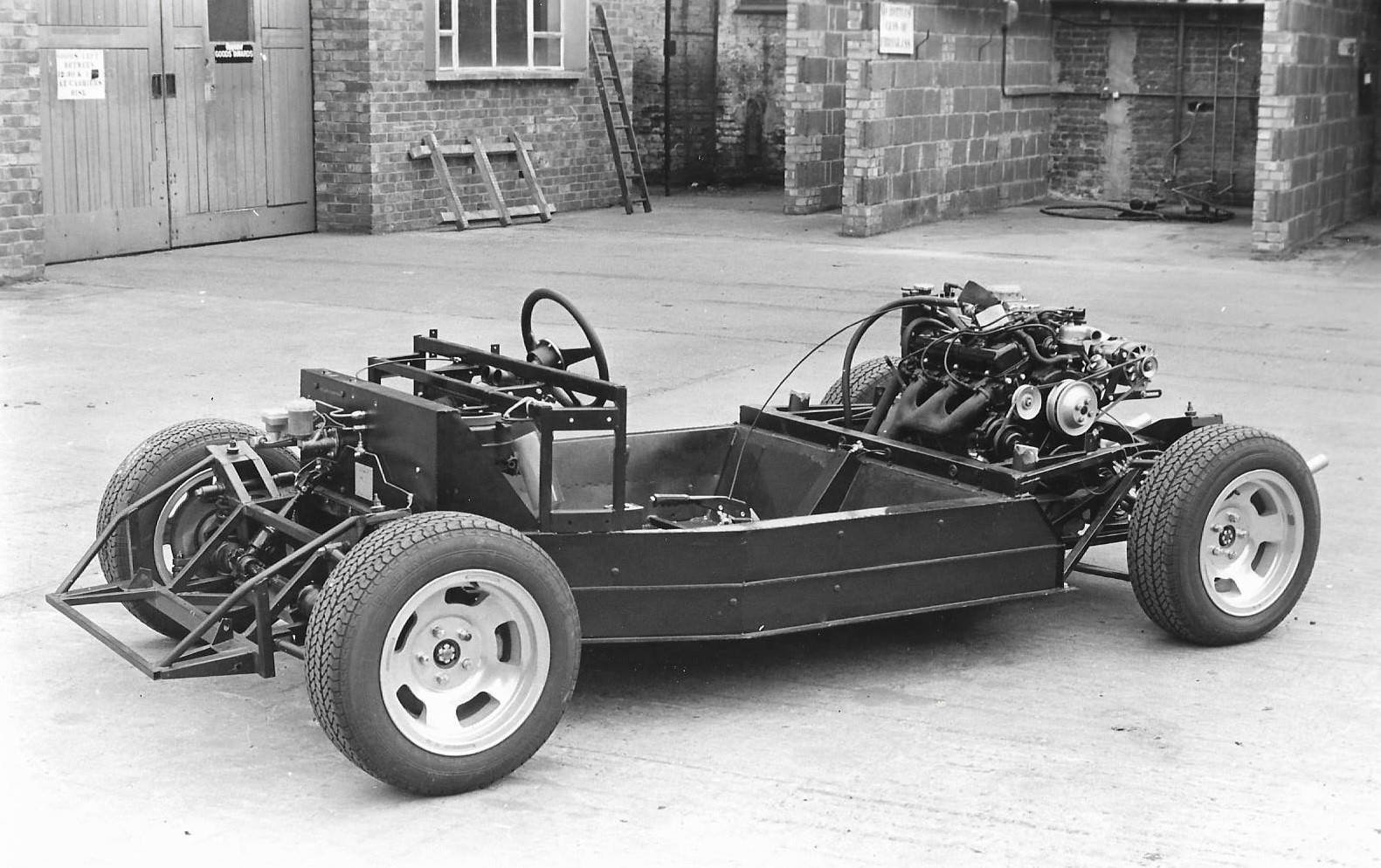

Even allowing for the skill of its creators, the Bohanna-Stables Diablo was an impressive achievement. Underneath its shapely GRP bodywork lay a tubular spaceframe chassis with independent suspension, disc brakes all-round and rack and pinion steering. Motive power came from a transversely mounted 1485cc BLMC E-series engine coupled with a five-speed gearbox, both taken from a BLMC development Maxi that Bohanna and Stables had acquired from a scrapyard.

Although its creators were prepared to put the Diablo into production themselves, it made more sense for them to hook up with a proven manufacturer. And as it happened, AC was about to end production of its low-volume 428 Frua model, thereby leaving it with the Model 70 invalid trike (which it supplied under contract to the Department of Health and Social Security) as its most significant product.

The obvious solution for both parties, therefore, was to strike a deal whereby AC would put the Diablo into production. And that’s exactly what happened, with both Bohanna and Stables being retained by AC as consultants.

Turning the Diablo into a production-ready car was no small task. The tubular spaceframe chassis was replaced by a robust platform-style tub with front and rear subframes. Out too went the E-series engine (AC having been unable to persuade BLMC to supply it to them) and in came Ford’s trusty 3.0 litre V6 Essex engine. Mounted transversely, this sat above a 5-speed Hewland gearbox within an AC-designed casing. The suspension, lights, interior and wheels also differed from the Diablo, and there were a number of changes to the bodyshell. Indeed, by the time that AC had finished, only the general shape and mid-engined layout of the Diablo were retained for production.

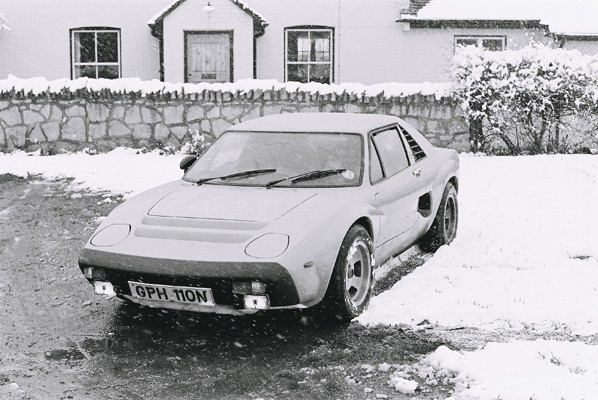

It says much about the speed at which AC worked that a non-running prototype, known as the AC 3000 (having previously been referred to as the AC 3-Litre), was displayed at the 1973 Motor Show. The styling changes wrought by AC had resulted in a pugnacious, ruggedly handsome sports car that attracted much interest from potential buyers, with around 300 orders reputedly being taken. It was anticipated that it would go on sale in 1974 at a price of between £3400 to £3800.

AC didn’t make that production target, but the first running prototype (now referred to as the ME 3000) emerged from the Thames Ditton works in 1974. Production was slated to commence the following year with the ultimate intention of building up to 40 cars a week. First, though, it would have to receive type approval.

The Motor Vehicle (Type Approval) Regulations were introduced in 1973, a consequence of the UK’s membership of the E.E.C. Although undoubtedly well intentioned, the Regulations were introduced in a ‘one size fits all basis’ that imposed a proportionately heavier financial burden on low volume manufacturers than mass producers. Moreover, the Regulations were something of a moveable feast, being frequently amended and expanded in the years immediately following their introduction.

One such amendment, made in 1975, imposed a requirement that a car’s steering column and shaft should not move backwards more than 5 inches in a head-on impact with a barrier at 30 miles per hour. When a prototype ME was subjected to this test at MIRA, the steering column was found to have moved back by 5.5 inches. AC therefore made substantial modifications to both the chassis and the front subframe. Although the changes had the desired effect – the ME passed the frontal impact test with ease when re-presented – they were costly to implement and caused the launch to be further delayed.

More bad news arrived in 1976 when the UK government announced that production of invalid tricycles was to cease by the end of March, 1978. The main reason cited by the government was their belief that the design of the invalid trike would soon fail to comply with road safety laws. AC argued that the trike could be re-engineered to meet these new requirements, but to no avail.

With their main source of income about to disappear, it was imperative that AC get the ME (now definitively known as the 3000 ME) into showrooms as soon as possible. But when it finally arrived in production form in 1978, inflation (a major factor, along with industrial unrest, throughout the 1970s, with rates reaching a high of 25% in 1975) meant that it went on sale at £11,032 – i.e. around three times the price that was originally projected. Moreover, it would now have to face competitors that had reached the market in the intervening years, including the Lotus Esprit.

There were other issues too. When driven by Motor in 1979 (the magazine having borrowed a car from Bell & Colvill), the ME’S handling gave cause for concern, with its stability on fast corners being particularly worrisome. Indeed, Motor’s Peter Dron was so perturbed by the waywardness of its rear end that he contacted AC, who recalled the ME in question and supplied another example in its place.

Keith Judd of AC explained that there was a problem with some batches of the Dunlop tyres with which the ME was equipped, and indeed the handling of the replacement ME was found to be satisfactory. That was, however, far from the end of the matter. Autocar’s otherwise very favourable 1980 road test of the ME also observed that its rear end was somewhat unruly, a view that was shared by Mel Nicholls of Car magazine. Nicholls, an admirer of both AC and the ME, went so far as to make several suggestions to AC as to how the ME’s handling might be improved. His efforts were, however, rebuffed by AC’s management, who said that the ME handled perfectly and that the problem lay with a lack of driving ability on the part of the journalists who had complained about it!

The ME’s engine provided a suitably muscular soundtrack, but its straight-line performance (120mph and 0-60 mph in 8.5 seconds) was perhaps a little underwhelming by class standards. That said, extracting more power from the Essex V6 was a fairly easy and relatively inexpensive process, with tuners the length and breadth of the UK having already gained considerable experience of tweaking the unit in its Ford Capri incarnation. For those in search of a more substantial hike in power output, Silverstone-based Rooster Turbos offered a conversion to forced induction. Twenty-one cars were thus modified, although several subsequently reverted to normal aspiration over the following years.

Rooster Turbos also offered a fix for the ME’s handling – a small change to the rear suspension geometry that markedly improved its rear end grip and stability.

The ME acquitted itself well in pretty much every other department. It was roomy, comfortable, had a good level of standard equipment and was well-engineered. It was, as Autocar put it, ‘a thoroughly likeable machine’.

That praise did not, however, translate into sales. The once-held thoughts of producing 40 cars a week were far removed from the reality that presented itself at the turn of the decade. With the revenue stream from the invalid trike having dried up and the ME’s development costs having run to a reputed £1,000,000, action had to be taken to shore up AC’s finances. And it was. The iconic High Street factory in Thames Ditton was sold for redevelopment and production was shifted to nearby premises in Summer Road. The dealer network went too, and by 1981 (by which time the price had risen to £13,301) buyers had to order an ME directly from AC.

Sales remained slow, but a potential saviour emerged in the guise of the Ford Motor Company. In 1980 Ford was looking for a new rally car to replace the Escort. Perhaps with the success of the Lancia Stratos in mind, the possibility of building a mid-engined rally car was explored. It thus transpired that Ford-owned Ghia obtained a complete (but unpainted) 3000 ME from AC as a platform for a design study on which a new rally car might be based.

Little more than four months later the fruit of Ghia’s labours, the AC-Ghia 3000 ME, wowed visitors to the 1981 Geneva Motor Show with its beautifully sculpted lines. And it wasn’t just the public who took to it, Steve Cropley of Car magazine delved deep into his inventory of superlatives after spending a day with it in Italy.

Having determined that their new rally car should be based on one of their volume sellers, Ford explored the possibility of putting the AC-Ghia into production anyway, but ultimately decided against it. With AC financially unable to proceed with the project on their own, the AC-Ghia was left to become a tantalising vision of what might have been.

Ford was not, however, the only American manufacturer who might have ridden to the ME’s rescue, for a Chrysler-engined version produced with the aid of Carroll Shelby was shown to Chrysler chairman Lee Iacocca. The story of the ‘Shelby ME’ began in 1980, when Barry Gale of US De Tomaso importers, Panteramerica, was given a passenger ride in an ME on a business trip to Belgium. Gale was impressed by the ME. So much so, in fact, that he and business partner Steve Hitter acquired the rights to sell it in the USA.

The duo then obtained an unpainted left-hand-drive ME without engine or gearbox and began the process of sourcing an American drivetrain with which to equip it. An approach to Carroll Shelby, who had just been contracted to produce performance versions of Chrysler vehicles, resulted in the procurement and fitting of a turbocharged four cylinder Chrysler engine and five-speed gearbox. The ME’s styling was lightly reworked, new wheels were fitted and the car was painted blue and silver.

It was in this guise that it was presented to Lee Iacocca when he visited the Shelby facility at Sante Fe. Unfortunately, Iacocca’s plans did not include the production of a mid-engined sports car and the project was quietly dropped.

The ME did, however, receive a fresh start of sorts in 1984, when a licensing deal was struck that saw production move to Scotland under the aegis of a new company, AC (Scotland) PLC.

With entrepreneur David MacDonald at the helm, AC (Scotland) continued to produce the ME whilst concurrently exploring the possibility of replacing the by now venerable Ford powerplant with Alfa Romeo’s modern Busso V6 engine. In addition, former BRM designer and engineer Aubrey Woods was brought on board and work commenced on a mark 2 version of the ME.

Unfortunately, financial problems brought an end to AC Scotland’s imaginative plans in 1985. Thirty cars had been built in Scotland, thereby taking total production of the ME to 104 examples since 1978.

There would, however, be one more chapter to ME’s story.

The mark II prototype was purchased by a new company, within whose ranks could be found Aubrey Woods and former Ford development engineer John Parsons, and reworked into a new car, the Ecosse Signature. With a redesigned body and motive power now being supplied by a turbocharged 2.0 litre Fiat engine, the Signature made use of an innovative, self-levelling suspension system that eschewed the use of coil springs.

A brochure was produced and two prototypes were built: the first was shown at the 1988 Motor Show and the second was tested by Performance Car magazine the following year. Although still clearly a development model, Performance Car thought highly of the Signature, with its performance (0 to 60mph in 6.5 seconds on a wet test track) and roll-free handling drawing particular praise.

But that was as far as it got. The Ecosse Car Company’s plans to put the Signature into production foundered on the same financial rock that had blighted the ME throughout its life.

Three decades on from its demise, what are we to make of the AC 3000 ME?

It would be easy to write it off as a failure on account of its sales performance, but to do so would be to disregard the fact that the ME had the misfortune to be born at a time of economic chaos and rampant inflation. It’s not, I think, too much of a stretch to say that in other, less fiscally challenging times it would have had a different fate.

What can be said with certainty is that it has great presence, goes well enough (and can be made to go even better with little difficulty), is well-engineered and has an enviable heritage. It’s durable too, the vast majority of production cars have survived to the present day. The AC-Ghia, Shelby Turbo and the two Ecosse Signature prototypes also still exist, along with the Lincoln Quicksilver, a futuristic, four-door Ghia-designed saloon based on an extended 3000 ME chassis. Even the Diablo, the car that started it all, will one day take to the roads again if owner Jeremy Witt’s plans come to fruition.

So while the best-laid schemes of AC and others might have gone astray, it’s fair to say that the ME didn’t just promise joys – it delivered them.

[We acknowledge, with thanks, the assistance generously provided to us in the preparation of this article by Terry Webb and Jeremy Witt. Header photograph by Peter Beale, supplied from the collection of Terry Webb.]

CLICK TO ENLARGE