"Every death in motor racing is a tragedy. But there can few figures lost to the sport who leave such a lasting legacy as Jim Clark. Crashing fatally at Hockenheim in April 1968, the Scottish farmer's son was only 32 when he "

Remembering Jim Clark

We visit the Jim Clark Museum

Take the speed of Senna, the wet weather prowess of Schumacher, the smoothness and mechanical sympathy of Prost, the versatility and enthusiasm of Andretti and the humility of a country boy and you’ve got the recipe for the greatest racing driver of the 1960s; indeed, perhaps the greatest racing driver ever.

That driver was Jim Clark.

Born in Fife but brought up in the Scottish borders, Clark made his Grand Prix debut for Team Lotus during the 1960 Formula One season. Two years later, he came within 20 laps of winning the world championship, an oil leak causing his Lotus to fall out of a comfortable lead in the season-ending South African Grand Prix. He made up for it the following season, taking seven Grand Prix wins, but lost out in 1964 when his Lotus again fell out of a championship-winning lead, this time on the last lap of the final race of the season. He did, however, win the British Saloon Car Championship that year at the wheel of a Lotus Cortina.

1965 was a bumper year for Clark, with another world championship, the first of three Tasman series championships (in only four attempts) and victory in the Indianapolis 500 all falling to him.

Lean times followed in 1966, with the introduction of a new 3.0-litre engine formula causing many teams, including Lotus, to have to rely on undersized engines for much of the season. When Lotus did finally bolt on a 3.0-litre engine, BRM’s H16 unit, it turned out to be overcomplicated, overweight, thirsty and unreliable. It says much about its woefulness that talents of the calibre of Clark, Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart could together coax but a single Grand Prix victory from it. Typically, it fell to Clark.

The 1967 season saw the introduction of the new Ford Cosworth DFV, which immediately showed itself to be the engine to have. Clark won on his first outing with it and took two further wins. He led every Grand Prix he contested in the DFV-powered Lotus 49, but time and again found himself having to retire due to mechanical woes. With better reliability, he would have strolled to the championship.

1968 started well, with Clark taking yet another Tasman championship and utterly dominating the South African Grand Prix. Another world title seemed to be on the cards, but Clark would never contest another Grand Prix.

On April 7th, 1968, Clark was driving in a relatively unimportant Formula 2 race at Hockenheim. On the fifth lap of the race, his Lotus left the road at high speed and struck a tree, fatally injuring him. Although no definitive cause for the accident has ever been established, a puncture to one of the rear tyres is the most likely culprit. Whatever the cause, Clark’s death shook the world of motorsport to the core.

There’s no doubt that Jim Clark was a superb driver, but just how deep did his talents go? Let’s look at some of the evidence.

Take, for example, the 1962 Nürburgring 1000km. On a wet track, Clark’s nimble but underpowered (it had all of 100 bhp) Lotus 23 pulled out a 27 second lead on the first lap alone. He was still leading when he was overcome by fumes from a broken exhaust manifold. And then there was the 1963 Belgian Grand Prix, held on the equally dangerous Spa-Francorchamps circuit and also run in wet conditions. In spite of race-long gearbox problems, Clark took victory (his second of four consecutive wins at the track) by nearly 5 minutes.

Consider also the 1967 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, at which Clark’s pole position time was 9.4 seconds faster than the next fastest man, Brabham’s Denny Hulme. Or the Italian Grand Prix the same year, in which Clark lost a whole lap due to a puncture yet fought back to re-take the lead, only to see victory snatched away on the final lap due to fuel starvation.

And for a final example, let’s leave Formula One and turn to USAC. Ever the enthusiast, Clark agreed to drive one of Rollo Vollstedt’s racers in the season-ending Rex Mays 300 at the challenging Riverside circuit in November, 1967. The Vollstedt hadn’t exactly shown itself to be the class of the field, and Clark was unfamiliar with it. Nevertheless, he duly stuck it on the front row of the grid, hassled pole-sitter Gurney into making an error and was leading the race until a rare error when changing gear caused him to damage the engine. In his race report for Car & Driver, noted American motorsport journalist Brock Yates said that Clark had driven the Vollstedt “faster than was thought capable by a mortal man.”

High praise indeed, but perhaps the final say should go to the Argentinian maestro Juan-Manuel Fangio, winner of five world championships in the 1950s. “Jim Clark,” said Fangio in 1967, “is outstandingly the greatest Grand Prix driver of all time.”

That is how good Jim Clark was.

It’s no surprise, then, that he continues to be revered by motorsport enthusiasts across the globe. And not just for his speed and victories, but for the way in which he achieved them. For Jim Clark was a gentleman, a modest soul willing to give advice and support to others, and someone who would never have dreamed of punting a rival off the road in order to gain a place.

For those who want to know more about him, all roads lead to the pretty border town of Duns, where for nearly fifty years the Jim Clark Room played host to a collection of the great man’s trophies, racing suits and memorabilia. It may have been small, but its appeal was powerful enough to entice even a certain Ayrton Senna da Silva to make the pilgrimage to it.

That room is no more, but in its place stands the new Jim Clark Motorsport Museum. Larger and airier than its predecessor, it makes use of both modern and traditional techniques to not only tell Jim Clark’s story but also give an insight into the times in which he lived and raced. There are two of Clark’s former racers on display, a Lotus Cortina driven by him in the 1964 British Saloon Car Championship and Lotus 25 R6, in which he scored four Grand Prix victories between 1964 and 1965.

There are trophies and mementoes aplenty, a large number of evocative photographs, interactive exhibits, a small cinema section, and a simulator in which visitors can take on Silverstone at the virtual wheel of a 1960s Lotus F1 car.

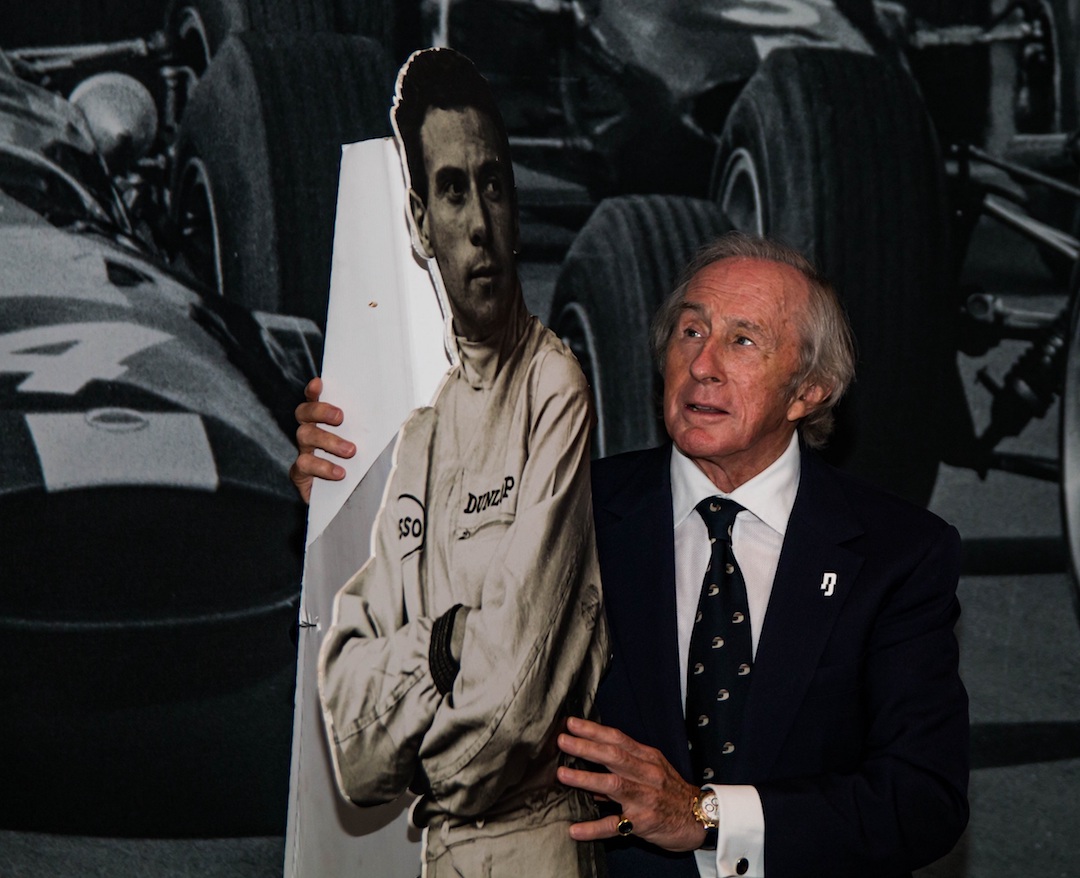

Having opened to the public on 11th July, 2019, the museum’s formal opening took place over a month later, with Clark’s great friend, rival and fellow multiple world champion, Sir Jackie Stewart, doing the honours.

Sir Jackie wasn’t the only well-known face from British motorsport who attended the opening, for Allan McNish, Gordon Shedden, John Cleland, Andrew Cowan and Louise Aitken-Walker were also present. Ian Scott Watson, who owned the car in which Clark competed in his first race, was there too, along with noted motorsport authors Graham Gauld and Eric Dymock. Members of Jim Clark’s family were also in attendance, as was his long-time girlfriend, Sally Stokes.

Having toured the new museum, which he described as “beautiful”, Sir Jackie then participated in a question and answer session, in which he spoke with feeling, candour and no small amount of humour about his great friendship with Jim Clark, of Clark’s natural brilliance at the wheel of a racing car, of Clark’s legendary indecisiveness outside of a racing car cockpit, and of the help and advice given to him by Clark. There was unconcealed emotion, too, as Sir Jackie described the familial nature of the Grand Prix circus of the 1960s, for the drivers then were not a collection of individuals who zoomed off in their private planes or helicopters after a race, but friends who travelled, partied and even went on holiday together.

It’s a period that, for me, is wonderfully summed up by a photograph taken in Graham Hill’s back garden that shows a smiling Jim Clark being pushed along on a toy tractor by Graham and Damon Hill. Needless to say, it’s on display in the museum.

But there was a very dark flip side to the bonhomie: motor racing in that era was deadly. For example, of the forty drivers who took the start in at least one round of the 1966 world championship, no fewer than fifteen of them – Clark, Rindt, Courage, Bandini, Spence, Pedro Rodriguez, Siffert, Scarfiotti, Bonnier, Schlesser, Anderson, John Taylor, Solana, Russo and McLaren – would die in racing or testing accidents over the next 8 years. The era of Clark and Stewart was unquestionably, as Sir Jackie said, a halcyon one, but it was also one tinged with more than a little tragedy.

Looked at from that perspective, the Jim Clark Motorsport Museum can be seen as not only a fitting tribute to a man who epitomised all that is good about sport but also as a memorial to a lost age and its fallen sons.

It’s not to be missed.

CLICK TO ENLARGE