"An M3 for the 1970s: focus on the legendary BMW 2002 Turbo When BMW moved away from naturally-aspirated power for the 2014 M3, slotting in a 3-litre twin-turbo powerplant, it left furrowed brows among traditionalists. But it was far from the first "

The Originals

The cars that made the mould.

Having an idea is one thing. Turning it into reality is, however, apt to be somewhat more challenging.

But for anyone or anything that succeeds in breaking new ground, enduring fame is assured.

Or is it?

We look at four cars that not only broke the mould but also shaped new ones, yet which (with one exception) have slipped into the twilight of obscurity.

Let’s meet them, shall we?

Bonnet Djet

The honour of producing the world’s first mid-engined production car belongs not to Lamborghini, Lotus or Ferrari but to a small and short-lived French manufacturer, Automobiles René Bonnet.

Founded in 1961 after René Bonnet split with his compatriot Charles Deutsch, with whom he had designed and built a succession of attractive sports and racing cars since 1938, Automobiles René Bonnet lasted less than four years before being swallowed by one of its creditors.

But if its life was short, its achievements were significant.

In 1962, the company’s new car, the Djet, a pretty two-seat sports car with a mid-mounted Renault engine, competed in both the Nurburgring 1000 kilometres and Le Mans 24 hours, with some success. Later that same year, a roadgoing version of the Djet (René Bonnet had prefixed ‘jet’ with a ‘D’ as he believed it was the only way to ensure that Francophones would pronounce it correctly) was launched at the Paris Motor Show.

With a remarkable specification for its day – steel spaceframe chassis, unstressed glassfibre body, disc brakes all round, independent suspension front and rear and, of course, its mid-mounted Renault engine – the Djet pointed the way forward for sports car design.

Four versions were offered. Djets 1 and 2 being for road use and Djets 3 and 4 being intended for competition. The roadgoing models came with 1108cc Renault engines in 65 (Djet 1) and 80 bhp (Djet 2) flavours, whereas their racing siblings featured DOHC 996cc Renault units.

Deliveries of the Djet commenced in July 1963, shortly after a streamlined version, the Aerodjet, won the prized Index of Thermal Efficiency at the Le Mans 24 Hours. But for all its sophistication and racing pedigree, the Djet struggled to find buyers. Price was the main issue, with even the base Djet 1 model carrying a price tag of 18,000 Francs.

In late 1964, weighed down by financial problems, René Bonnet reluctantly agreed to sell his car company and its product lines to Engins Matra, the makers of the Djet’s bodyshell.

Matra took over production, sorted out some of the Djet’s flaws and foibles, reduced the price and rebadged it as a Matra-Bonnet. The Djet name was retained for a while, but the final version dropped both the Bonnet name and the ‘d’ from ‘Djet’. Matra’s marketing, better funded and more effective than that of Bonnet, was undoubtedly helped by the French government’s decision to present Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, with a Djet. The result was that Matra was able to find buyers for the Djet at a rather higher rate than its originator – of the 1691 Djets built from 1962 to 1967, all but 198 were constructed by Matra.

Matra went on to create a series of inventive, successful and influential cars for both road and track, including the Rancho, the Renault Espace and the MS 80, the car that took Jackie Stewart to his first World Driver’s Championship. But it all started with René Bonnet’s lovely little sports car.

BMW 2002 Turbo

Let’s get it straight from the outset: the BMW 2002 Turbo was not the first production car to be turbocharged. Not by a long shot – the Chevrolet Corvair Monza and Oldsmobile Jetfire both beat it to the market by more than a decade.

It was, however, the first European production car to be turbocharged. As such, it was the founder member (the Porsche 911 Turbo and Saab 99 Turbo being its cohorts) of an unholy trinity of 1970s turbo tearaways.

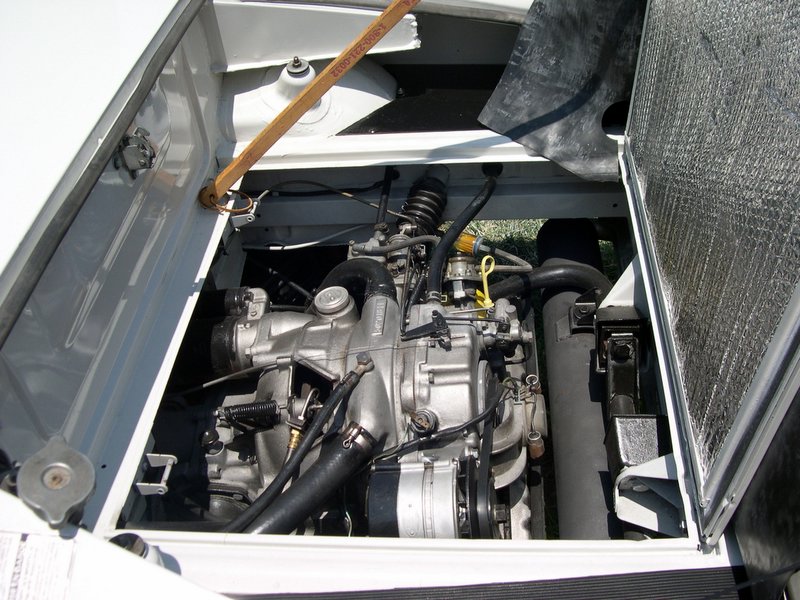

Its roots lay in the European Touring Car Challenge (as it was then known), in which a turbocharged 2002 vanquished the Porsche 911 in a straight fight. But as BMW looked towards campaigning larger, naturally aspirated cars on the track, thought was given to producing a turbocharged 2002 for the road. And in 1973, that’s exactly what they did.

It wasn’t as though the 2002 range lacked a high-performance version. After all, the 2.0 litre normally aspirated 2002 Tii was both powerful (130 bhp) and quick (116mph and 0-60 mph in 8.3 seconds) by the standards of the day. But whereas the soberly dressed Tii was something of a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the 2002 turbo was anything but.

It sat on wider wheels than lesser 2002s and its large front air dam, riveted fibreglass wheelarch extensions and boot-mounted spoiler bestowed it with more than a hint of belligerence. But it was the decals, which bellowed ‘2002’ and ‘turbo’ in mirrored print from either side of the front numberplate, that really caught the eye.

Needless to say, the decals were deemed in some quarters to be too aggressive. The resulting outcry was such that BMW decided not to supply them as factory-fitted items. They did not, however, go quite so far as to prevent them from being available through the dealer network…

The free publicity generated by the decal controversy would have been to little avail if the 2002 turbo had failed to live up to its pugnacious appearance. But with both power (168 bhp) and torque (178 lb. ft) being in generous supply, there was little danger of anyone kicking sand in its face. Its top speed of 130 mph was 14 mph better than the Tii could manage, and a whole second was shaved off the Tii’s time from rest to 60 mph. On the flip side, there was a generous portion of turbo lag and the binary power delivery was typical of the first couple of generations of turbocharged cars. That said, it was less a problem than something to which one had to become acclimatised.

Perhaps mindful of the Tii’s reputation for being lairy at the limit, BMW equipped the turbo with wider tyres and firmer suspension than its less powerful sibling. And, conscious of its extra torque, they endowed it with a limited-slip differential. The result of these changes was a rather less lurid driving experience than the Tii, albeit drivers not used to the ways of its engine could find themselves having to cope with the arrival of a tidal wave of boost in mid-corner.

It was a fine car, then, and one that would only have got better but for the 1973/4 energy crisis. In the face of fuel shortages and rising prices, sales of performance cars slumped and BMW decided to end production of the 2002 turbo in 1974. Only 1672 examples were built in its short life, but the impact it made is still as intense as the sight of those decals in your rear-view mirror.

Simca 1100 TI

The adage that no-one remembers who finishes second emphatically does not apply when it comes to the history of the hot hatch. For the car that’s regarded as the progenitor of the type, the Volkswagen Golf GTI, was not in fact the first of its kind.

Instead, that accolade belongs to that most unlikely of contenders, the Simca 1100 TI.

Yes, it only had a 1294cc engine and sounded like the annual French knitting championships in full swing, but as we shall see the hallmarks of the classic hot hatch – extra power, beefed-up suspension and brakes, go-faster interior and exterior enhancements and marketing geared to appeal to enthusiastic drivers – were all present and correct.

When launched in 1967, the 1100 was a step forward for small family cars. Its front-wheel-drive layout, rack and pinion steering, all-independent suspension, transversely mounted engine and hatchback configuration endowed it with a winning combination of space, practicality, supple ride and secure handling. And all at a very reasonable price.

It sold well too, with annual production reaching almost 300,000 in 1973. Even so, the 1100 range lacked a little oomph, with the most powerful model for the first three years of its production life offering a meagre 56 bhp.

That changed with the introduction of the 75bhp 1100 Special in 1970. Extra power aside, though, there was little else to immediately distinguish the Special from its siblings. That charge could not, however, be laid at the door of the ultimate 1100, the TI.

Launched in 1973, the TI featured the same 1294cc engine as used in later versions of the Special, but with the addition of two twin-choke Weber 36 DCNF carburettors that lifted power to 81 bhp – enough to propel the TI top speed of over 100 mph and cover the 0 to 60 mph dash in a smidgeon under 12 seconds.

There were other mechanical changes too: the clutch, brakes and alternator were all beefed up and firmer dampers were fitted.

The interior and exterior were not overlooked either. Considered in retrospect, the TI’s external and interior enhancements are nothing less than design templates for the hot hatchbacks that followed in its wake. There were alloy wheels, additional front lights, a black grille, bonnet-mounted TI badge and discrete front and rear spoilers. Inside, the TI had a six gauge instrument panel (de rigeur on 1970s cars with sporting pretensions) and a bespoke steering wheel boss with ‘TI’ logo. And to further ram home the point that the TI wasn’t just any old 1100, both the external TI badges and the steering wheel logo had red highlights.

Simca’s marketing also set the TI apart from its stablemates, with sales brochures invariably featuring a shot of a TI under hard cornering. And if that’s not quintessential hot hatch advertising then I’ll eat my hat.

The TI never came to the UK, alas, but it remained part of the core 1100 range in continental Europe until 1978. Simca was acquired by PSA Peugeot Citroen later that same year and disappeared as a marque shortly thereafter, thus giving the 1100 TI the dual distinction of not only being the first hot hatchback but also the only one to sport a Simca badge.

NSU Spider

It was created by a company that had started out as a manufacturer of sewing machines, its engine was the brainchild of a man who never held a driving licence and it paved the way for its maker to launch possibly the most stylish and inventive car of the 1960s.

It was – and is – the NSU Wankel Spider and it was the first production car in the world to have a Wankel rotary engine.

The Spider’s story began in 1929, when Felix Wankel, a young German engineer without formal qualifications, obtained a patent relating to an internal combustion engine that dispensed with reciprocating pistons in favour of a triangular rotor that rotated within the combustion chamber.

Wankel’s design had several obvious advantages over conventional piston engines, particularly as regards size, weight and smoothness. But it would be twenty-eight years before Wankel, by then working for NSU, produced a working prototype of his engine. Much to Wankel’s disdain, however, NSU preferred a simpler version produced by his colleague, Hanns Dieter Paschke. Three years later, in 1960, the Wankel engine (in its simplified, Paschke-designed form) made its first appearance in a car, a converted NSU Prinz.

In 1963, NSU unveiled their first Wankel-engined production car, the Wankel Spider, at the Frankfurt Motor Show. Powered by a light and compact single-rotor engine, the two-seat, Bertone-designed Spider tipped the scales at just 699 kilogrammes.

The Spider’s lightness helped to ensure that it made the most of the 50 bhp produced by its rear-mounted engine, being able to achieve 92 mph and sprint from rest to 60 mph in 16.7 seconds. There was, however, one caveat: in a bid to prolong engine life, NSU suggested an engine speed limit of 5000 rpm for everyday use, which considerably blunted the Spider’s performance.

Better performance could easily be accessed by taking advantage of the engine’s smoothness and willingness to rev far beyond its suggested engine speed limit, but drivers who did so would soon learn that this extra oomph came at a price, and not just in terms of fuel economy.

Leaving its radical engine aside, the Spider was a fairly accomplished vehicle in itself. With all-independent suspension, front disc brakes and rack and pinion steering, its ride, handling and stopping abilities were all more than acceptable. It looked good too, but storage space was rather limited and a degree in Applied Faffery was needed in order to single-handedly raise and lower the soft top.

Its great weakness – the propensity of its rotor tip seals to wear at an accelerated rate – would become evident later, but for would-be purchasers in 1964 the Spider’s most immediate flaw was its price: in the UK, it cost more than twice as much as the MG Midget and Triumph Spitfire. Consequently, sales were slow and only 2375 were built before production ended in 1967.

The car that replaced it on the NSU production lines, the uber-stylish Ro 80, wowed the world and pushed its older sibling out of the limelight and into the long grass of anonymity. But the Spider will always have one thing over the Ro 80: it was the first.

Four rather different cars, then. Each has its own particular charms but there’s one thing they all share in common: none of them were ever built in RHD form*. Still, that’s no reason to grumble if you own one. After all, you’ve got an original…and that’s enough.

*Okay, Bonnet made a couple of Djets in RHD to special order, but the point stands!

CLICK TO ENLARGE