"Back in the 1980s, car manufacturers were busy thinking of the next big thing in the sports car world, and some clever German folk had an idea. Why don’t we connect all of the wheels to the engine? Why "

LeMay, A-bombs and sports cars.

Who is General Curtis LeMay?

By 1953, the United States had almost 1,000 nuclear bombs waiting to be dropped. The future of sports cars wasn’t at the top of Gen. Curtis LeMay’s priorities.

It’s the 1950s. In the hushed offices of the military leadership across the US, conversations simply unfathomable to most modern minds were taking place. Should the US, with its massive nuclear stockpile, strike first and annihilate the Soviet Union to never again be preoccupied with its threat? In the war rooms of the West, moral lines were being sketched and stretched.

Depending on where you stand, Curtis LeMay is either a morally reprehensible war criminal, or a war hero who saved many more lives than he ended. In 1950, General LeMay urged the US Government to implement ‘SAC Emergency Plan 1-49’ – the dropping of 133 atomic bombs on 70 Soviet cities in the space of just 30 days. By the end of that decade he’d increased the scale of those plans. He’d help draw up preparatory operations that would lead to the vaporisation of more than 100 Soviet cities and 645 military sites in the space of just 24 hours. As hard as it is to believe, while these plans were all being put together, Curtis LeMay was also lending a hand to the Sports Car Club of America.

LeMay forms the mould for what many of us would identify as the stereotypical US General. He was brash, abrasive, outspoken and hungry, and you’d rarely see him without a big cigar between his teeth – he was even alleged to have flown with one. The line “bomb them back to the stone age” is often attributed to him and bombs were certainly his forte. During the Second World War, LeMay directed the infamous fire bombings of Japan as well as the dropping of ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’ upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki. F.J. Bradley’s book ‘No Strategic Targets Left’ estimates that between March and August of 1945, LeMay’s campaign killed more than 500,000 people, and left more than 5,000,000 homeless.

From 1948 to 1957, LeMay headed up ‘Strategic Air Command’, the wing of the US Military responsible for the majority of strategic nuclear striking. SAC’s motto was “Peace is Our Profession”, a particularly chilling slogan given its role and LeMay’s heavy-handed approach – see Korea and Vietnam – but he firmly believed that his actions were justified, stating that he felt a brief period of immense violence could bring peace more quickly, as well as be preferable to a prolonged period of the very same evil. While the conversations and planning for eradication of the USSR was taking place, LeMay was using his role as head of the SAC to allow the Sports Car Club of America to use airfields and military bases to hold events. He rented out facilities under his command to the SCCA, with the profits gained from such events going towards the Airman’s Living Improvement Fund.

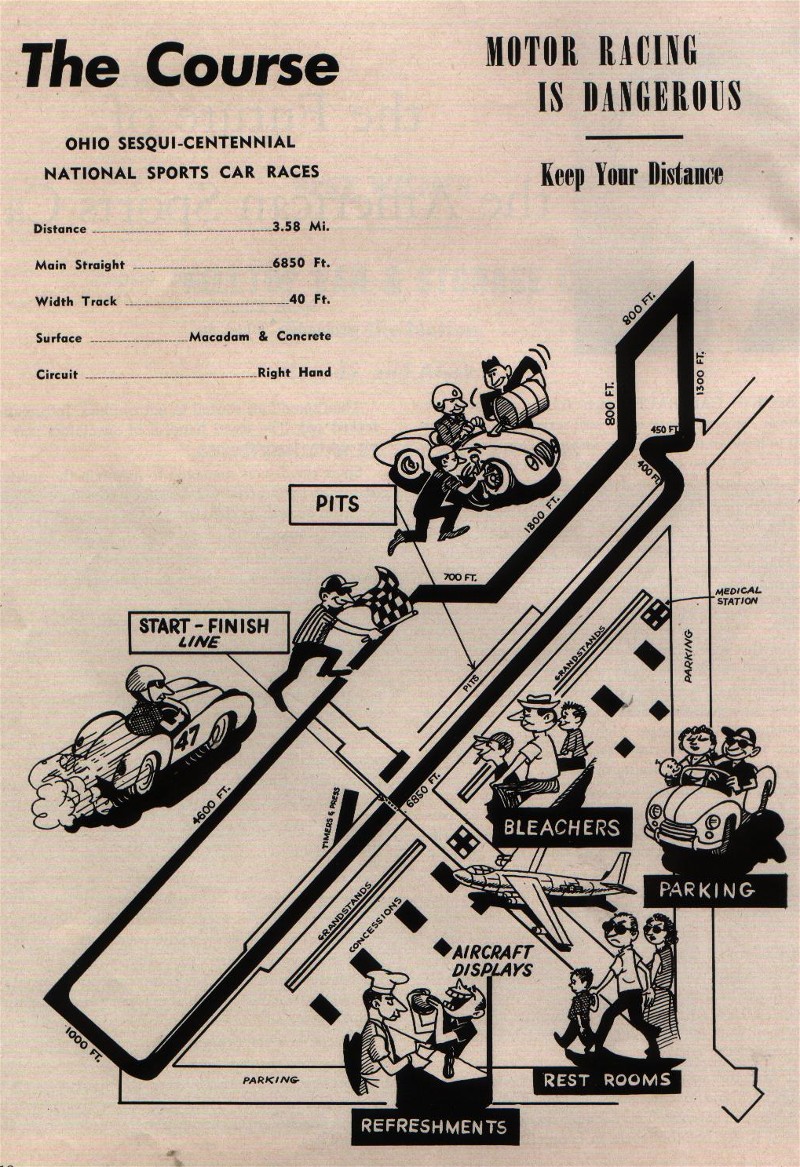

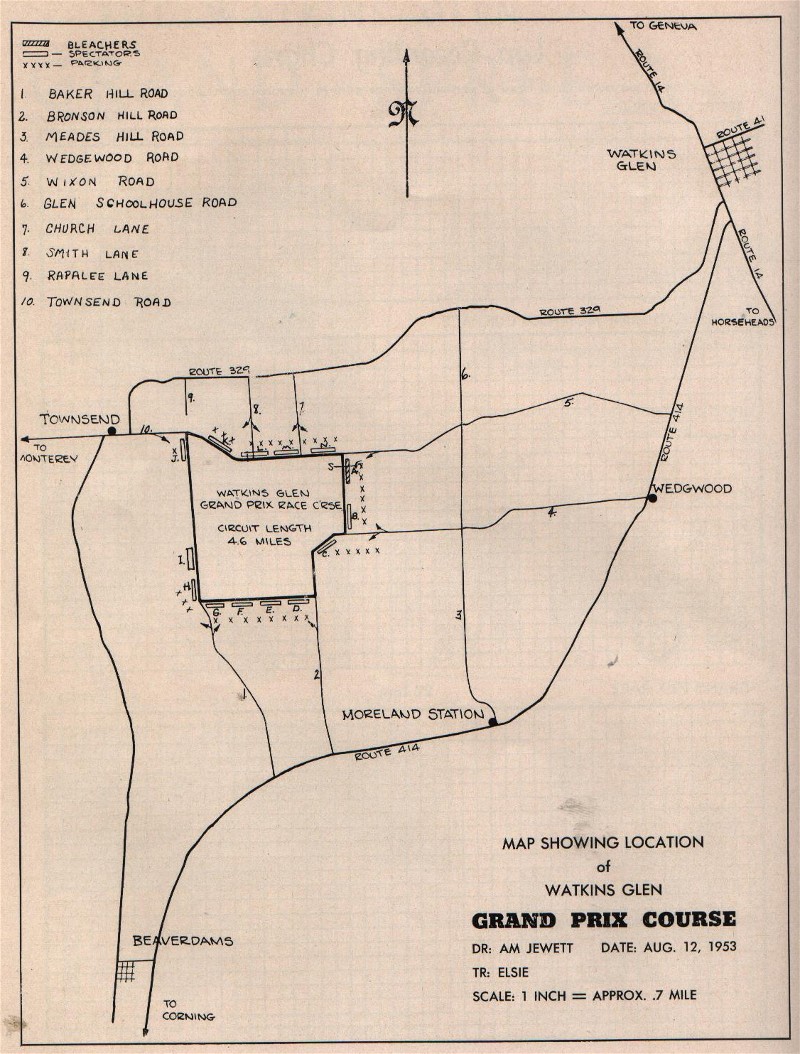

In Britain, we know just how well old airfields can make for excellent racing circuits, some of the UK’s finest tracks are built upon such sites, but LeMay and SAC’s sites were still in service and ready for the Third World War to kick-off. Some of the finest sports cars of the early 1950s such as Ferraris and Jaguars flew down the very same runways as B-36 Peacemakers and B-47 Stratojets. At this time, war with the Soviet Union was expected to come at any moment, so little to no modifications to the sites were permitted to take place. However, the facilities were an upgrade on small settlements and street circuits which were endangering spectators and drivers – there were no trees or rocks for cars to run off into next to an airfield and moving the races to sites like this even briefly took the heat of the SCCA, which was suffering now from a negative public opinion.

LeMay was passionate about motor racing and even owned an Allard J2, though he was prevented from competing due to his ranking and importance in the US chain of command. Important he was to the SCCA too, which awarded him the Woolf Barnato Award – the club’s highest accolade – in 1954. A 2-year deal struck in 1953 saw SAC facilities all over the USA used for SCCA events, allowing circuits and facilities to upgrade to greater standards of safety and take sports car racing off the streets.

Without LeMay’s offer, it’s quite possible that sports car racing could have come to complete halt in the USA in the early 1950s, and American motorsport owes him a great debt. It is remarkable to think that amongst a backdrop of nuclear war, Curtis LeMay still found time to think about his cars. Now that’s passion.

CLICK TO ENLARGE