The Austin Allegro is the home-grown car the British most love to hate, or at least mock.

Its faults have been catalogued at length, from its ‘Quartic’ steering wheel, its grinding gearchange and its questionable build quality, among other glitches and foibles.

But was it really that bad? We trawl back through contemporary road tests; some of them may surprise you.

First, a challenge. Try to find an article of the 10 worst cars ever made that doesn’t mention the Allegro.

We couldn’t, although we did give up after page four of Google. Even in lockdown, some things are a waste of time.

It’s always there, often vying with the Morris Marina for top spot. When Jeremy Clarkson put the two head-to-head he said: “Deciding which one is worse is like deciding which leg you’d rather have amputated.”

For the record, he thought the Allegro was less bad. So that’s good, right? A win’s a win.

And if you’re looking for another semi-comedic rant about how the ‘All Aggro’ was an embarrassment to the British motor industry, and British Leyland in particular, you’re in the wrong place.

The internet already has tens of thousands of words banging that particular drum.

After all, many of the 640,000 people who bought the Allegro during its 10-year production run liked them just fine, and the 200 or so owners who keep the remaining cars on the road must really love them…

To people of a certain age they carry a certain retro cachet, whether that’s just a love of the underdog, or a kind of motoring shabby chic, or because they conjure memories of childhood or their parents or grandparents.

What’s more, road testers of the time had plenty of nice things to say. Were they just rooting for the British car out of patriotism, or did they actually like it?

The long birth of ADO67

The design programme for ADO67, the car that would become the Allegro, began in 1968 as the newly-merged British Leyland sought a long-term replacement for the best-selling ADO16 – the 1100/1300 range.

It was a lengthy process, with the priority to move the Morris Marina into production to compete with the Ford Cortina – and anyway, ADO16 was still selling phenomenally well, with 1968 and ‘69 its peak years of production.

Leyland boss Donald Stokes wanted to position the company’s Morris marque as straightforward Ford-fighters, with Austin to create more avant-garde cars, a little bit special and technologically advanced.

Hence designers Harris Mann and Paul Hughes were given a brief to design something completely new, rather than the previously mooted ADO16 rehash, codenamed ADO22.

Mann’s sleeker, more rakish design was chosen for further development.

What happened next is well-documented: Mann’s design, while still just about recognisable, was heavily compromised by the need to use existing engine and gearbox set-ups, and other larger parts that had to be made to fit.

As well as the existing A-series engines used in ADO16, the Allegro had to house the far larger, E-series unit from the Maxi, which Mann said in 2002 “was more suitable for putting in a Leyland truck”.

The final Allegro design

The end result was a somewhat taller, squashed version of Mann’s more wedge-shaped vision, the wheelbase only slightly longer than the car it was to replace.

Mann later described the eventual car as “shorter and stumpier” than he had wanted, with thicker seats cutting down on interior space.

“It was getting bulkier inside and out, and lost the original sleekness,” he said. “That was what happened unfortunately.”

Mann would realise his wedge-shaped dreams on the Princess and, more successfully, the TR7.

Under the compromised skin, the most significant change from the ADO16 was the switch from hydrolastic suspension to hydragas, replacing rubber as the springing material with gas and nitrogen spring units to provide a softer ride.

It was again interconnected front to rear, leaving the roadholding largely unchanged.

Two of the most bone-headed decisions taken in the car’s development were the infamous ‘Quartic’ steering wheel, rectangular with rounded sides, and the misguided belief that only the Maxi should have a hatchback to maintain its unique selling point in the company’s range.

Sadly, it was Allegro, and not the Maxi, that would compete with more versatile hatches like the Renault 5, Golf and later Alfasuds.

The steering wheel was variously described as “absurd” and “idiotic”, but was implemented, according to Vic Hammond, chief interior designer, to provide a better view of the instruments and to enhance the car’s forward-looking appeal.

It was dropped after a couple of years.

Launch and reaction

After a £21million development, the Allegro was launched with great optimism in May 1973, with up to 1,200 cars a week rolling off the production lines at Longbridge.

In an attempt to be “all things to all men”, the car was offered in 12 variations of engine size and trim, from 1100cc up to 1750cc, with two doors or four, and generous equipment levels for the time.

It was very much the expectation that the Allegro would carry all before it, both at home and abroad.

Britain had just joined the Common Market, the forerunner of the European Union, and the Allegro would, in the words of Lord Stokes, “appeal not only to the sophisticated British public but to the sophisticated European public”.

“We set our engineers, our designers, a challenge,” he added. “I’ve watched it from all stages of development. I’ve driven it at all the stages of its development and I’m absolutely convinced that they’ve got a car here which is quite outstanding in its class and its type.”

But what of those early road test reports?

Autocar took delivery of a 1300 Super De Luxe for its May edition, and was largely complimentary, praising the Hydragas suspension as a “significant step forward” and the “impressively smooth” ride.

The magazine grumbled about its slower performance than the Austin 1300 and, of course, the steering wheel, finding it “hard to understand why this gimmick was thought necessary, especially as it is bound to introduce some initial sales resistance”.

But, overall, the magazine was preparing for the car to be a success.

“There is no doubt that a lot of thought and development has gone into the design of the Austin Allegro and it is bound to be a very popular new model,” it said, the car “very good value for money” at about £1,100 on the road.

Motor got their hands on the more powerful 1750 SportSpecial for their launch test, and wrote of its good handling, smooth ride and good sound proofing at speed, as well as its good value (at £1,366) and high equipment levels that “will make even some of the Japanese importers blush”.

The jury was out on its “rather squat, chunky lines”, but “the thoroughness with which it has been equipped and protected against corrosion are beyond question”.

Major criticism was reserved, again, for the “absurd” steering wheel, “a ridiculous device that we all detested”.

“It feels unpleasant and makes smooth driving around tight bends very difficult, especially when straightening up as your hands are thrown off the rim by the ‘cam action’ of its corners,” it wrote.

Performance was a little disappointing for a supposedly sporting car compared to rivals like the Renault 16TS and Triumph Dolomite, while there were moans about a lack of rear legroom and the vague and notchy gearchange.

But, on balance, not the worst car in the world.

Adrian Flux Classic Car Insurance

The Allegro’s styling

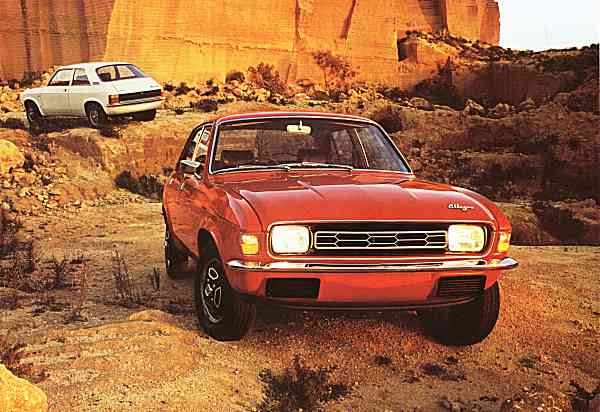

Those early tests were non-committal on the Allegro’s styling, which would certainly not be the case for a new car launched today.

We now know it was never intended to look like this, and there’s no doubt the corruption of Mann’s original design resulted in a bloated looking car with too narrow a grille and bulbous sides.

CAR magazine was another to be rather more kind than the majority are today, even saying it was a “vast improvement” over the Pininfarina-styled 1100/1300 models – a bold claim that few would agree with today.

They didn’t really agree at the time either – while ADO16, in all its variants, sold about 2.3million worldwide, the Allegro barely reached a quarter of that.

“The Allegro has created a good deal of discussion,” CAR wrote in August 1973, measuring a 1300 up against a VW Beetle and a Simca 1100. “Some like its shape, others are non-committal.

“It looks as though some conscious styling effort has been put into it, but we would have preferred the sort of shape that would have people saying ‘I must get into one of those’”.

Maybe if BL had stuck to Mann’s original design, they might have done.

Again, though you’d never know from CAR’s report that this car was destined to become a laughing stock, describing it as a “notable step forward for BLMC”, while having room for improvement.

“With some degree of self-levelling the suspension would be superb; with a round wheel the steering would be excellent; with better damping on the front end noise on really bad roads would be eliminated; with a better located engine, exhaust breakages could be stopped.”

But if “development proceeds rapidly the Allegro could become an all-time great”.

Yes, an all-time great in the making!

CAR holds its line

On to February 1974 then, and CAR was holding the line that the Allegro was, actually, pretty good.

Pitting the 1750SS against an Alfasud and Citroen GS, it wrote: “We have steadfastly maintained that the Austin Allegro is able to hold its head high when marching in company with those two indomitable Europeans, the Citroen GS Club and the Alfasud.

“Now we have given it a chance to show its mettle, eyeball-to-eyeball with the Continental duo.”

It wasn’t an entirely equal match-up because it was based on price, and the 1750 found itself up against a 1220cc GS and an 1186cc Alfa.

On styling, very few would say now about the Austin that its “bodywork is new and successful: on the showroom floor the Allegro gives nothing to its rivals”.

At the wheel, however, the magazine failed to justify its great hopes for the British car, describing the E-series engine as seemingly “manufactured from masonry, with bricks for cylinders”, and a clumsy gearbox.

The Austin was better value for money, had good parts availability by comparison, and a good finish, but was “not a particularly inspiring car to drive; the other two outshine it comfortably with superior handling and roadholding”.

Autocar tested the same car in August, and wondered why the sporting model was still using the single carb version of the 1750cc Maxi engine, despite there being a twin-carb version available.

Overall though, it was happy with the “quiet work which has been done on it, and it combines enough virtues to be an attractive package”.

Twin-carb Allegro

The magazine got its wish later that year, with the arrival of the top of the range, twin-carb 1750HL, which boosted power output from 75bhp to 90bhp.

It could outsprint such distinguished rivals as the Renault 16TS, Triumph Dolomite and, way above its class, the Rover 2200TC, hitting 60mph in a heady 11 seconds.

The engine was still far from smooth, but Autocar described it as “an eager performer”, albeit with too much understeer on fast corners.

And the Quartic wheel was gone, on this model at least.

“We trust we shall find round steering wheels on all Allegros soon,” the magazine said, a wish that was granted the following year.

“Although there are several points needing improvement still, notably in handling, this was an Allegro which we enjoyed driving. It is certainly practical in many ways, and above all performs very well for its class.”

By May 1975, the Golf had arrived to provide some stiff competition, and with a hatchback that the Allegro should have had all along.

CAR pitched an 1100 Allegro against a Golf and Fiat 128 saloon with similar sized engines.

Again on the styling, there was not a murmur of criticism: “The Allegro is distinctive and sensibly styled without being trendy and shows the promise of longevity if its makers can resist the temptation of adding tinsel.”

The ageing A-series engine, a three-main-bearing pushrod, found it tough to compete with the more powerful continental cars, which both utilised alloy engines with cranks running in five main bearings and valves operated by overhead camshafts.

“The Allegro lacks performance, and does not compensate sufficiently by being notably more economical,” it said.

“It’s also short on rear leg room and handling feels curiously out of date, although the level of roadholding is high. The gearchange and odd steering wheel contribute nothing.”

There was clearly much development work to do if the Allegro was to compete with the new competition from abroad.

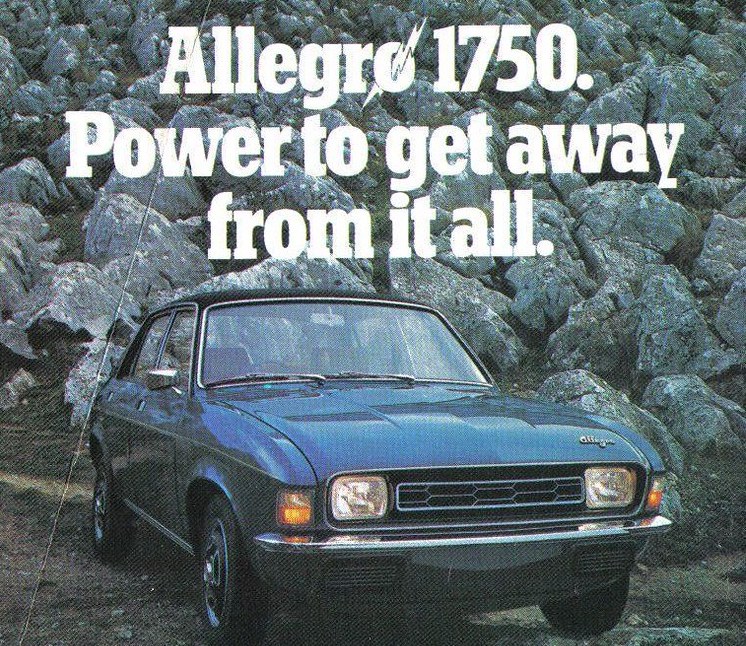

Like our illustration of the Austin Allegro at the beginning of the article?

Download a free high-quality poster version here.

Development and a European flop

By now, problems with build quality were well-known and sales were not hitting the ambitious targets set by BL bosses.

In 1974, the Allegro was Britain’s 7th best-selling car – not bad at all, but not a patch on the all-conquering ADO16, which topped the charts every year between 1964 and 1971, apart from when the Cortina briefly took its crown in 1967.

An awkward-looking estate had failed to catch the public’s imagination, and the Vanden Plas 1500, complete with ostentatious grille and never badged as an Allegro, was heavily criticised.

The bold predictions that Europeans would fall in love with the car proved unfounded, with the vast majority of vehicles sold on the home market.

The Germans, French and Italians much preferred the Golfs, Citroens and Fiats produced at home.

Innocenti did build an Italian version of the Allegro, called the Regent, but it was quickly dropped when sales failed to take off.

Leyland bashing became a national sport, and scare stories about the car’s shortcomings proliferated in the press, most famously when a lack of structural integrity occasionally saw the rear window popping out when the car was jacked up.

This, and other problems, like the wheels falling off if the nuts had not been tightened to strict instructions, resulted in the “All Aggro” nickname.

Bosses at BLMC were quick to try to correct criticisms, launching the Allegro 2 at the 1975 London Motor Show.

Testing an 1100DL, Autocar noted that it was “refreshing to find Leyland acknowledging most of the criticisms of the first car”.

There was extra space for driver and rear passengers, while small telescopic dampers were added to each front mount to improve refinement and ease of smooth driving.

And the Quartic wheel had been firmly consigned to history (though never forgotten).

“In general then, the Allegro 2 is an improvement on the first model, though there is room for further advance,” said the magazine. “It is easy to drive, comfortable, and generally very practical.

“It must be regarded as a well proven car by now, with no radical new items to arouse suspicion, and we hope to see it helping to restore Leyland’s fortunes in the future.”

Testing the range-topping 1750HL, however, the magazine felt that it lacked the pizzazz of rival sports models like the Alfasud Ti and Golf LS, and the style and comfort of cruisers like the Citroen GS.

Just weeks before the launch of the Allegro 3 at the end of 1979, the 1750cc Equipe arrived to compete with the Golf GTi and Ford Escort RS.

The car featured extravagant red and orange stripes, Starsky and Hutch style, along metallic silver bodywork, with a deep matt black spoiler and alloy wheels.

The interior was jazzed up by orange and black check-patterned cloth seats, an all-black roof lining and alloy-spoked steering wheel.

Motor asked if this “image boost” would “live up to the promise of its looks?”

“What the Allegro has always lacked is any real visual zest to give it immediate impact in the showroom and dissolve its rather bland and staid image,” it wrote. This was to be the answer.

The magazine’s answer was ambivalent: “The Allegro doesn’t shine, but neither is it disgraced” when compared to its rivals.

It was never intended to be a permanent model, with a limited run of 2,700 cars, used more as a tool to draw attention to the model in the hope of attracting younger buyers.

These days, they are a highly desirable slice of retro for the Allegro aficionado, with only nine thought to have survived.

The Allegro soldiers on

Preliminary design work for a new platform, which would spawn the Allegro’s successor, the Maestro, was already under way when the old car was given one final upgrade in 1979.

The Allegro 3 was given a wide range of new colours, new lights inside a new grille, wraparound plastic bumpers and a sporty front airdam, with many models featuring twin headlamps.

Fuel consumption was improved and, inside, a new dashboard livened things up. Had it become a “good car”?

Here’s Motor magazine testing a twin-carb 1.5HL in February 1980: “The latest Allegro is, in many ways, a much improved car.

“Although an advance on its predecessors…it remains overall a mundane device in relation to the opposition.

“There is only one area – the gearchange – where it is exceptionally poor but on the other hand it is hard to single out any other area where it’s notably better than its rivals.”

So, definitely better, and not the worst car ever made, but it simply couldn’t compete with newer, more advanced rivals.

High praise for the Vanden Plas?

No article trying to find the positives for the Allegro could overlook CAR’s road test in August 1989, written by the late, great Russell Bulgin.

The test pitted an ageing Vanden Plas 1500 against the new Ford Orion 1600e and Vauxhall Belmont CDi in what was billed as “a battle of the style giants”.

“Look at the Austin Allegro Vanden Plas,” he began. “Look hard – and, in the purity of its discreet front-end layout, its perfectly balanced mix of regal radiator grille and rectangular headlamps, you can see the inspiration behind the nose styling of the Jaguar XJ40.

“For, as Jaguar’s pencil men so obviously realised, the Allegro Vanden Plas is a seminal British car design, combining classic elegance with the timeless appeal only a real commitment to quality can engender.

“The Allegro’s subtle grille, especially when combined with the model’s distinctively sleek, svelte lines, makes it an easy winner in the pub car park glamour parade. An understated elegance pervades the car.

“In no way does it resemble an ordinary tin box that has been warmed over with a grotesquely crude nose job.”

Vicious parody? Er, yes, but the Vanden Plas was a profitable, if low-volume part of the Allegro range, so some will have agreed with Bulgin, even if they were the “retired music teachers and elderly kerb crawlers” he describes.

The Allegro bows out

After nearly a decade in production, the Allegro bowed out in March 1982, with enough old stock in showrooms to keep it on sale into the following year alongside the Maestro.

Its sales never hit the heights of its predecessor, but the motoring world had moved on – there was far more competition from abroad, and people who had bought the 1100/1300 had moved up to the ever-growing Cortina and Cavalier.

There’s no doubt it wasn’t a good looking car, but it could have been. There’s no doubt it had multiple issues, many of which were ironed out over the years.

Does it deserve its reputation as a laughing stock, and the car that ruined British Leyland?

No, not really. It was hampered by uninspired styling and early reliability and build quality issues, as well as that infernal steering wheel.

It never fully recovered, but it did improve and the nation’s contemporary road testers refused to condemn it as simply rubbish.

There are now only around 700 Allegros of all types left, on and off the road, according to government data.

Get one while you can!