"The problem with roads is that they have rules. The good thing about offroad culture is that there aren't as many. Whether you like it or not the road is in itself a piece of administrative coercion. No matter what "

Off road riding: The freedom principle

Do you remember the first thing that made you dream of motorbikes? For me it was the final sequence of Bruce Brown’s 1972 epic homage to American motorsport On Any Sunday.

I can’t remember how I came across it – probably via my hip uncle who as well as a Chevy impala, a mk2 jag and a Jensen Healey had in his garage a couple of old ‘scramblers’, which he let me and my cousin thrash around liberally on local waste ground down by the Thames. That dream-like sequence, in which Steve McQueen and two buddies (was one of them stunt double Bud Ekins?), tear up a dune system in the lowering light, seems to me the foundation myth of a certain sort of off-road motorcycling. It is irresponsible. It is unruly. It is heartbreakingly atmospheric.

The sequence makes you realise it is possible to feel nostalgia for a time you never knew.

The freedom principle lodged at the heart of the motorcycling impulse, and which for me is crystallised in those couple of minutes of cinema, is at times difficult to excavate. Clogged highways tend to spoil the biking dream. Hyper-inflated traffic regulation kills the free and easy vibe.

But it occurs time and time again, as I circumnavigate these islands, that one thing we aren’t lacking in is space. Archaic trespass laws and nanny state regulation is real – but between the hedges in the nooks and corners of the nation — from the moorlands of the west country to the heightening fells of the northern uplands – there are quiet thoroughfares, often ancient and beautiful, that are just begging to be explored on two wheels, with motor.

With this in mind we hooked up in the byways of Surrey with three very different kinds of motorcyclists. Just a stone’s throw from the smoke Nick Ashley, Lucia Aucott and James ‘leftie’ Smith showed us the sort of boundless love of riding that’s nurtured and promoted when you take to the leafier thoroughfares. Our trio of friends probably don’t fit the image of the average British green laner. The inappropriate but undoubted style of Nick’s ride is matched only by his cool and laconic take on the beauty of the back roads. Lucia’s enthusiasm and love for the trails is infectious – and James’s knowledge that freedom is on our doorsteps inspires us to look beyond the A-roads for our hard-won pleasure.

GREEN LANING: regulation doesn’t end at the byways. You still have to be road legal to ride on lanes designated at motor-vehicle friendly. But then again, any machine can be ridden in these fun thoroughfares. But of course, there are many ways to enjoy the knobblies. Here are three of the most popular offroad disciplines – and a fistful of our favourite machines that will help you enjoy the ride…

Trials

Trials riding developed in motorcycling’s earliest years – when manufacturers keen to demonstrate the strength and reliability of their machines initiated a series of ‘reliability trials’. The idea was to spotlight how well their bikes could perform over multiple days in rough terrain – with the right rider. The Scottish ‘Six Day Trial is often spoken about as the oldest motorsport event in the world – and was the beginning of a series of multi-day offroad events.

These epic tests of reliability, tenacity and endurance were never meant to be about crossing the line first. The challenge was to simply traverse the kind of terrain that would have been impossible to negotiate on any other machine – and to do so with style and the kind of control and panache that means that a simple foot down would lose you buckets of kudos. Though the machinery has of course changed massively over the century of the scene’s development, as has the format of the pro events, what remains true and consistent that trials riding is a true test of skill, sensitivity and precision – across the controls.

In fact, this is the motorsport where the body is perhaps most engaged. Machines are honed to favour torque over base power, throttle sensitivity over blatty open wristed madness. The slow, methodical trad style of trials riding has been challenged over the last couple of decades by a new generation of BMX and MTB influenced riders. These young guns began to look at trials obstacles in a freestyle influenced manner, introducing the arcane art of the bunny hop to proceedings. Rather than looking at a line in terms of a continuous flow, pulling up the nose and bouncing on the rear wheel, or simply hopping both wheels off the ground simultaneously, allowed the rider to hop straight up on rocks, logs, roots – and draw new lines and new types of personalities into the sport. The flat caps are still involved of course – there’s a wealth of knowledge and development of machinery that the pioneers created – but Trials is now free to explore the wildest terrain — and these days has a refreshed aesthetic.

The Machines:

Contemporary: GAS GAS TXT

GAS GAS is now owned by the behemoth KTM / HUSQVARNA conglomerate – and by many accounts the two stroke 250 version of the TXT trials bike is a winner. Weighing in at only 148 pounds, it comes with sticky tyres, without a seat and the radical geometry of the latest crop of triallers.

Classic: Montesa 247 Cota Montesa (one s)

Classic trials riding was all about waxed jackets, horrible weather and up close and personal audience interaction. Funky little European machines like the Montesa Cota fit into this landscape perfectly. The machines were all about solid build and reliability – and the aesthetic holds water with the alt.bike aesthetic.

Motocross

If trials is the technical, almost contemplative form of off road motorcycling, then motocross is it’s snarling, irresponsible, outrageously brash and noisy little cousin. But there are as many connections and similarities between the two forms than you would think . The two sports are, after all, out of the same litter. Motocross as we know it exists in a colorful array of different guises – from closed circuit races in stadiums with specially sculpted courses, split into staged ‘motos’ of specific duration — to the spectacular performative freesport that is Freestyle MX. But the sport incrementally emerged from the original trials scene in the pre WW2 era when organisers dispensed with the technical judging aspect in favour of the simple format of ‘first across the line wins’. Known as scrambling for years – particularly in its earliest manifestation in these islands, all the British manufacturers got involved – and BSA came to dominate in the immediate postwar years. Totemic bikes from European builders like Husqvarna and Bultaco built some of the most progressive and pretty bikes later in the mid-century until the Japanese manufacturers moved into the frame across the board in the 1970s. What characterises the Motocross bike is of course yards of suspension travel and the kind of power-to-weight ratios that would put a NASA machine in its place. Where in the sixties and seventies, the bitey power banded madness of the two-stroke engine dominated, emissions regs and improved technology meant that four stroke machines became increasingly popular. Motocross is the one off road motorcycling discipline that has made the jump into ‘freesports’ and its garish aesthetic has created a powerful and influential industry.

CLASSIC: Husqvarna 450 WR

Offroad motorcycling doesn’t get more pretty – or more totemic than this. This is the very Husky owned by Steve McQueen – yes the one high sided with style in that dreamy sequence at the end of On Any Sunday. By the early seventies these Swedish brutes had made the clunking British offroad machines look archaic – and the five speed gearboxes and twisty engines in these lightweight frames were dominant – until the Japanese came and changed everything.

Contemporary: Husqvarna FC450

Half a century later, and the Husky 450 format is still almost recognisable. There’s a lot of convergence in Motocross these days – when tech and CAD define everything. But when you get under the different coloured plastics, the Swedish crossers claim all sorts of incremental tech and material tweaks – like carbon fibre subframes, low mass-shift crankshafts and all sorts of trick airflow tech. We don’t understand much of this — but there’s something about the Husky stance that stands out from the crowd.

Dakarisme

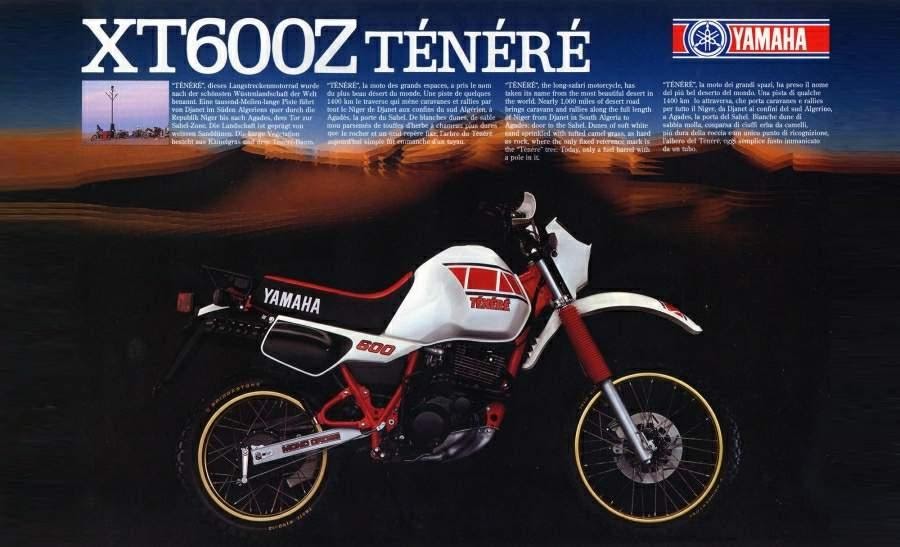

Ok, we might be coining a term here. We’re not too sure. But there’s a way of being when riding a behemoth tourer like a 1200 BMW GS series bike, that is kind of different than how you normally see them ridden. The vast majority of these uber-capable machines, which were originally bred for tearing across continents at speed with little crisp, multi-pocketed Gore-Tex, with an even crisper, showroom finish on the mechanicals of the machine. First sight of the bulging tanks and extended forkages of the machines inspired by the popularity of the Paris Dakar ‘raid’ races was in the early 1980s, when Yamaha’s brutally dashing Ténéré (named after the African Desert) was spotted gracing many a Parisian or Roman Boulevard – not because of their off road ability of course – but simply that they looked badass. There was something about these bikes that played into the styled out Paninaro aesthetic – though the legendary Italian sandwich bar hanging casual kids couldn’t afford them at the time. This was the eighties after all – and the Paris-Dakar race was, like Group B rally, the epitome of irresponsibility. In the 1983 race, forty riders famously got completely lost for four days, before limping home with broken bones and dehydration and a rakish kind of swagger. It’s that man-against-nature aesthetic that you’re buying into when you swivel the eye to these bikes. From the GS series of Beemers to the Africa Twin and Royal Enfield’s Himalayan – they are solid, capable machines that whisper the truth that at any time, with the right load of camping gear – you could take off on the road (and off). Forever.

Yamaha’s Ténéré took the already popular XT format and jacked it up in every dimension. From the tank to the shocks and from the brakes to the build, this is the machine that proved most popular with punters in the wake of Paris-Dakar’s televisual popularity. It graced many a Parisian boulevard and a Roman piazza – tapping into a fashionable eighties aesthetic as well as proving itself out there in the desert.

The latest ‘Rally’ edition of the Ténéré is a beautiful thing too. Packed with add ons from the standard, like that 4mil aluminium bash plate, a higher-up double foamed saddle to ease the thigh and glute load – the classic format remains – and that blue and yellow colourway references one of the original ‘raid’ colours too.

CLICK TO ENLARGE