"Everyone remembers Colin Chapman, the genius of Lotus. The educated remember Alec Issigonis who gave us Minor, Mini and 1100. A sainted few Remember William Lyons, the man behind Jaguar and its most iconic creations – XK120, MkII and E-Type. Few, if "

Dante Giacosa’s unsung genius

His name doesn’t come up as much as you might expect...

Even inside the circles of obsessive car nuts, you’ll find the names of Porsche, Piech, Ford, and even Issigonis spoken more often. There is no question, though, that this man had at least as much, if not more, influence on the cars we drove yesterday, and the cars we drive today as anyone from Stuttgart, Detroit, or Longbridge. As a bonus, he had the coolest name of any car engineer, ever — Dante Giacosa. Everything sounds better in Italian…

Born in Rome in 1905, and the son of a policeman, Giacosa put his engineering genius down to something quite prosaic — a knowledge of Latin and ancient Greek that gave him, so he said, “a sense of measure and balance without which I could not have done my job”

Whatever it was that kick-started his brain, by the age of just 22, in 1927, he had a job at one of the greatest of all car makers, and certainly the kingpin of Italian industry; Fiat. It didn’t hurt that the arrived with both a degree in mechanical engineering from Turin Polytechnic and a letter of recommendation from Vittorio Valetta, Fiat’s general manager and the man who would do much to shape and direct Giacosa’s talents over the next fifty years.

He actually started his work by designing aircraft engines, massive multi-cylinder, supercharged designs that would be a huge variance from the small, affordable cars with which he would eventually become synonymous.

Giacosa’s life in small cars began in 1929. Much like his contemporary, Ferdinand Porsche, Giacosa’s careers was transformed by a Fascist government, as a diktat came down from the office of Benito Mussolini, via that of Senator Giovanni Agnelli, co-founder of Fiat itself, that what Italy needed was a small, affordable car which could seat two adults and two children, and which could be bought for just 5,000-Lire.

Fiat’s then-chief designer Oreste Lardone came up with a car using an air-cooled engine, but when a prototype caught fire with Senator Agnelli on board, it’s no surprise that Lardone was given his cards, and the way was open for Giacosa.

Originally called the Zero A, and only later called 500, his design was tiny and simple, using a 500cc water-cooled engine, and measuring just over three-metres in length. It was reliable and astoundingly cheap to buy, and Fiat would sell more than half-a-million of them before the Second World War brought an end to the model’s life. With its distinctive sloped radiator and guile-less expression, it was quickly nicknamed Topolino — the Italian for Mickey Mouse. As with the Model T in America, the Volkswagen Type 1 (OK, Beetle) in Germany, and the Austin 7 in Britain, the Topolino put Italy on wheels.

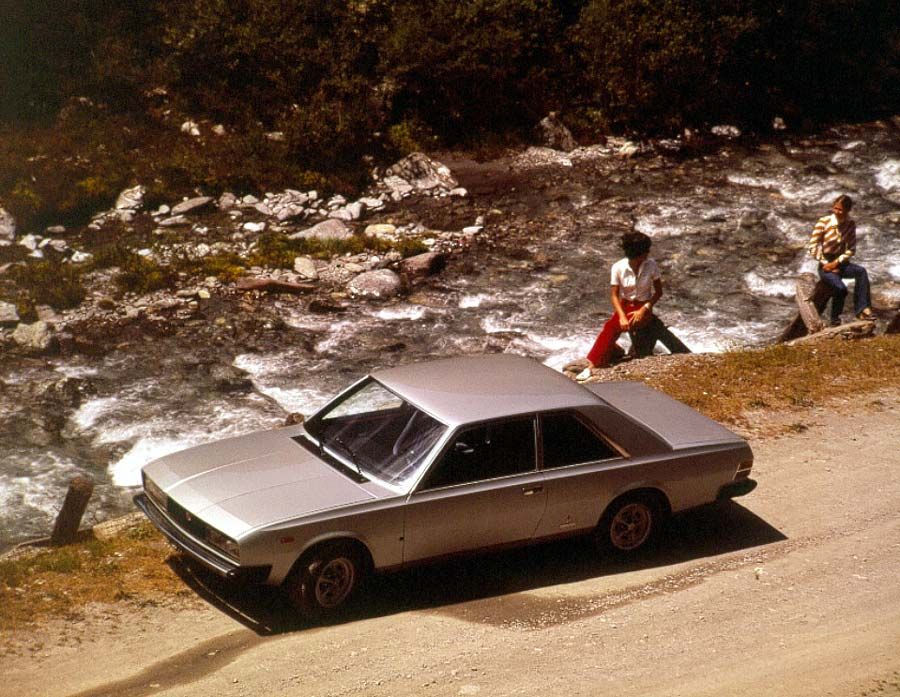

It was the beginning of what you might call a calling for Giacosa; the design and production of small, affordable cars. Although he would go back to work on aircraft engines during the War, and would later work on such ostentatious models as the Fiat 130 saloon and Coupe, and the Ferrari-engined Dino Coupe and Spyder, Giacosa’s heart always lay with the simple and cheap. Writing in his autobiography, Forty Years Of Design With Fiat, Giacosa said “large automobiles, intended for the privileged few have never much appealed to me. I had never shaken off my taste for the small and the economical, the sort of auto that can have the widest possible ownership, a taste instilled in me in my first years of work with Fiat.”

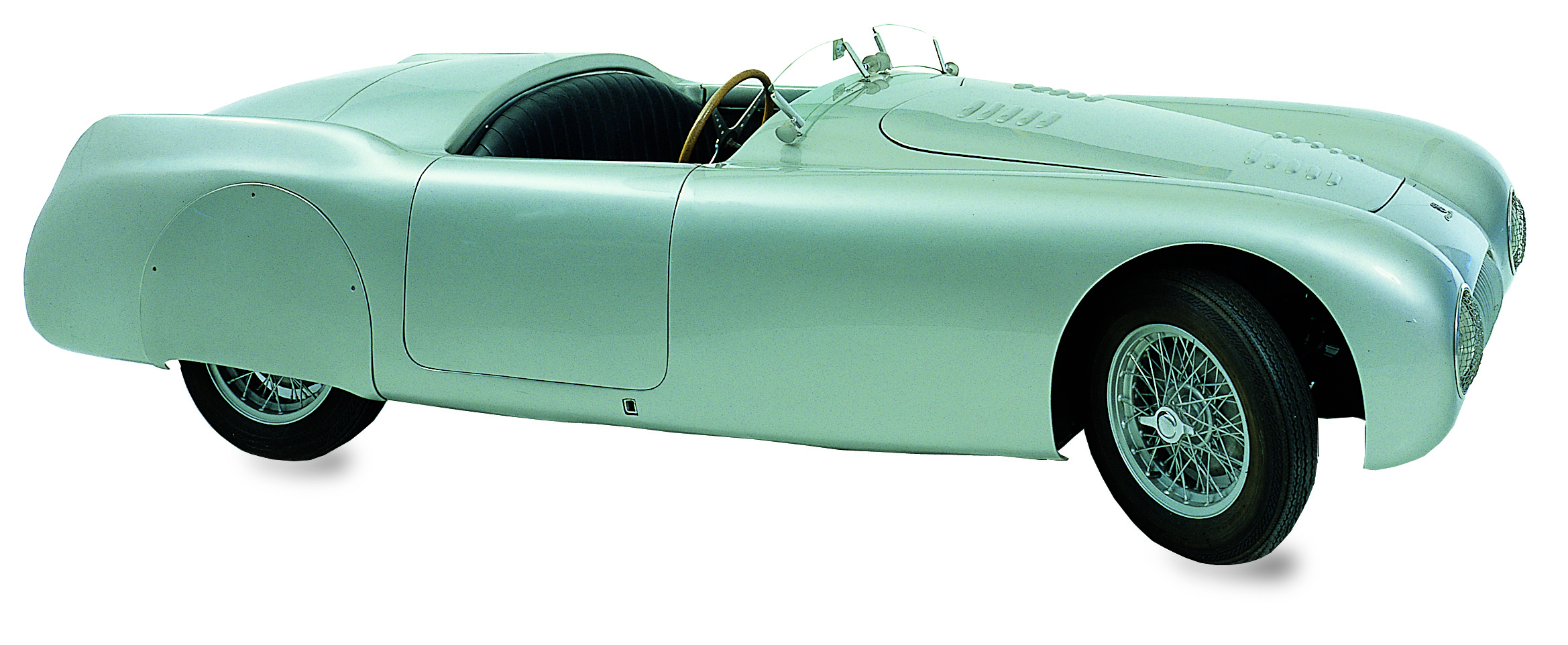

Mind you, he would also be instrumental in the creation of one of the greatest and most beautiful sports cars of all time, the Cisitalia. In 1946, when Enzo Ferrari was just getting started again, Piero Dusio, then the president of the Juventus football club, decided he wanted to create a fast, but low-cost, racing car to revive motorsports in Italy. Although it wasn’t strictly a Fiat project, the management decided that Giacosa could work on it, and he combined Fiat’s own 1,100cc engine and a beautiful, bespoke space-frame aluminium chassis to amazing effect. The Cisitalia raced in 1946, driven by pre-war aces such as Tazio Nuvolari, Piero Taruffi and Louis Chiron, and was an instant winner. Better yet, later on, one was draped in bodywork designed by Pininfarina, creating a car that was so beautiful that to this day one is on display in the New York Museum Of Modern Art as a perfect example of automotive sculpture.

Giacosa’s next project was the 600, a small rear-engined car (not entirely unlike the designs of the revived Beetle and Renault’s 4CV) which would revive family motoring in post-war Italy. Again, designed to be simple and rugged, it took the Topolino concept and expanded it so that now there was space for four adults. Or even six — there was the 600 Multipla, a tiny egg-shaped MPV that pre-dates the Espace by three decades, and which has recently been used by Apple as an inspiration for whatever the electronic giant’s car project ever turns out to be. The 600 also began Fiat’s relationship with governments behind the Iron Curtain, the design being licensed to Yugoslavia for production. It even formed the basis of Seat’s first car in Spain.

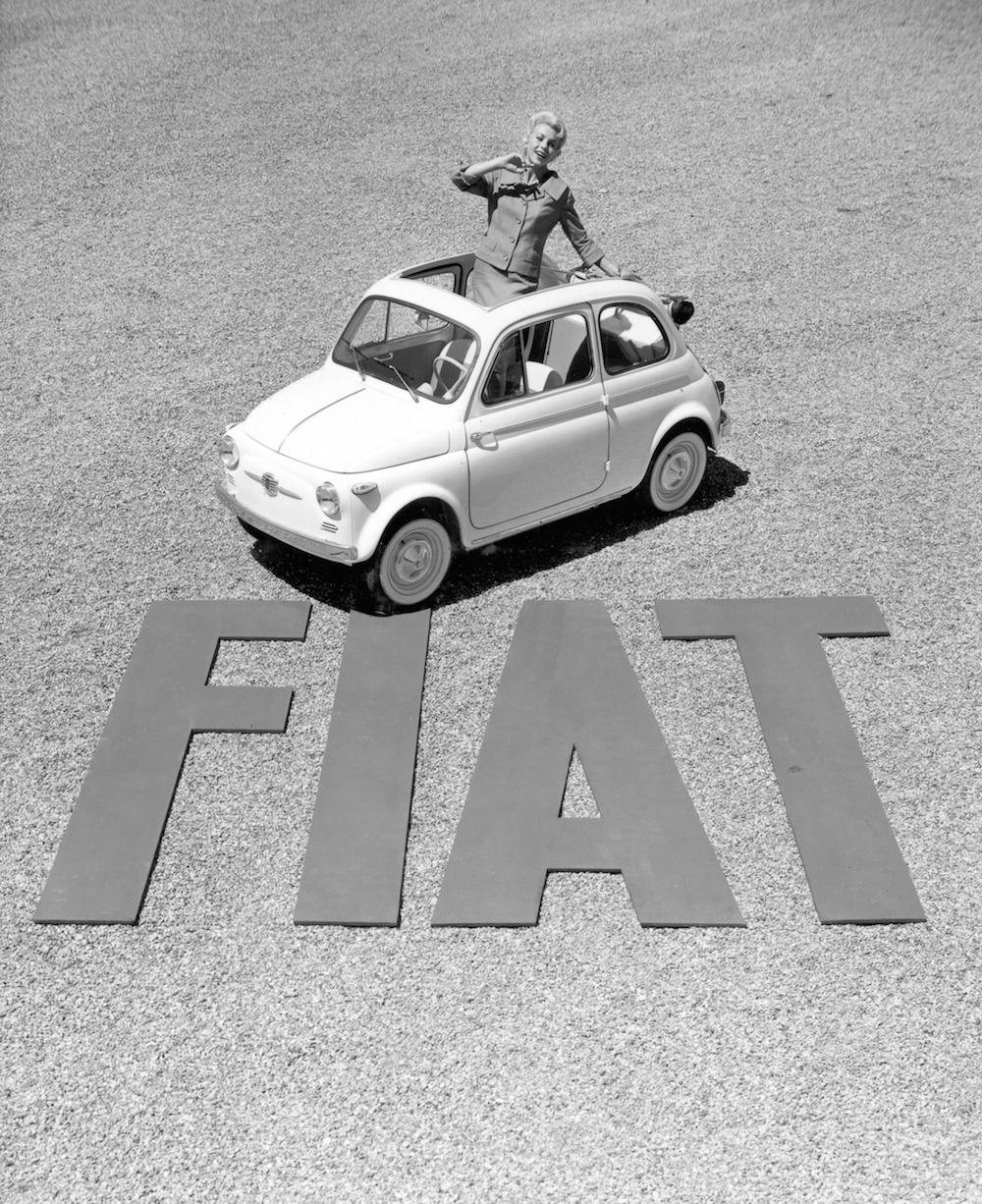

That was not Giacosa’s finest hour, though. That would come next in the shape of the Nuova 500. Launched in 1957, the 500 was intended to be the smallest, simplest car into which you could squeeze four people and an engine. Rear-engined and rear-wheel drive, it became a staggering success for Fiat. Almost four-million would eventually be sold in a long lifetime, and it would become such a totem for Fiat that not only are original 500s still prized today as useable cars, perfect for tiny medieval city streets, but the design would be revived wholesale by Fiat in 1997, creating the current 500 — a car that sold so well it effectively saved Fiat from bankruptcy.

Giacosa, ever the restless engineer, wasn’t happy with the 500 though. He felt it was usurped in design and engineering by Alec Issigonis’ Mini, which came along two years later. In his book, Giacosa writes that he should have pressed ahead with a more daring design and layout for the 500, saying “the appearance of Alec Issigonis’s Morris Mini in 1959 had been a discouraging blow for us all. I knew that the Morris company had been testing the vehicle for some time but I never imagined it was so small and so amazingly successful in design. I was shaken and felt regretful that I had not persisted with my studies for a front-driven transverse-engined auto after the design for the little “100” in 1947.”

For his valedictory lap, though, Giacosa would make no such mistake. Effectively head of every Fiat car project from the end of the Second World War to his retirement in 1970, Giacosa worked on a staggering range of cars, from the ground-breaking 124 saloon (which would lead to another Soviet collaboration, creating the Lada company) to the gorgeous 8V (pronounced Otto-Vu) sports car, to research into gas turbine engines.

Arguably, though, his most influential creation was another supposedly humble family car, the 128. While the Mini has pioneered front-wheel drive, its gearbox-in-the-sump layout made for inherent reliability and servicing issues. For the 128, Giacosa set about taking the front-wheel-drive setup and perfecting it. What he came up with was a transverse engine, with the gearbox mounted separately, driving the front wheels through unequal-length driveshafts. Sounds banal, but Giacosa first introduced it on the small-selling Autobianchi Primula in 1965, carefully honing the layout until it was ready for the 128 in 1969. Beating the likes of the VW Golf and Ford Fiesta into production by at least half a decade, the 128 is one of the most influential front-driven designs ever, and chances are the car sitting on your driveway right now uses an identical mechanical layout.

As Giacosa himself said “of all the Fiat models and – if I may be permitted to commit a sin of pride and say so – probably all the autos the world over, the 128 is probably the one that gives the best “value for money”. The arrangement of the engine and transmission, previously used on the Autobianchi Primula, started a trend that has become widespread owing to its extreme simplicity. It was applied sometime later to the little Japanese automobiles, then to the new Volkswagens and the Ford Fiesta, and it is still finding converts.”

And that was it. In 1970, Giacosa resigned, feeling that he had reached what was a fair retirement age and that it was time to make way for new blood. He would continue in the role of consultant for Fiat for some time, but he never again designed another car. He watched, and bemoaned, as the job of chief designer slipped from a position of prominence to that of functionary. He would likely detest the current motor industry, with its insistence on marketing research above all else. Even as far back at 1979, Giacosa was scathing about ‘modern’ industrial methods, saying that what they mostly did was stifle design. “Creativity lies at the heart of design and manifests itself through draughtsmanship, the indispensable means of expression, the designer’s first and most valuable instrument,” he wrote. “The design engineer should be aware of this and proud of it. A verbal description is not enough in technology. The drawing, embodying the design, is essential: redo it over and over again, perfect it until it is (I won’t say certain, because nothing is certain in this world) at least highly probable that it will fulfil the result aimed at. The work of draughtsmanship stimulates the imagination, increases one’s inventiveness. These considerations concern mankind in general and I should like to develop them further. Creativity is man’s ability to produce new things, innovations in the unbounded sphere of science, technology, philosophy, every field of human activity as in art. It is felt as a natural drive towards possible new experiences. Scientific theories are generated by the creative imagination.

“The use of electronic computers leads to a tendency to treat every problem as if it were an exercise in systems analysis, distracting attention from the work or designing. In my opinion, the mind loses in flexibility, the imagination becomes ossified and the insight needed to solve problems is blunted.

“No other machine gives that personal sense of extending and enhancing one’s physical and mental powers. Of all the inventions of the past century, the auto is the one that has made the most profound impression on our way of life. It has freed the individual from the trammels of time and space. The range of our activities and the scope of our work have been immensely enlarged. It has created a broader sphere of interests and made a major contribution to the rapidity of change, steadily increasing until a few years ago, that distinguishes our modern civilisation.”

In this modern age of enormous teams of engineers and designers working on multiple cars at once, we won’t see Giacosa’s like again. And that should be worrying, not least for the boardroom masters of car companies. After all, none other than Paolo Cantarella, Fiat’s mid-nineties CEO, opined on the day of Giacosa’s death in 1996 that ”I would say Giacosa made Fiat what it is today.”

Without Giacosa, what will become of Fiat, or any car maker, tomorrow?

CLICK TO ENLARGE