"A thunderstorm is looming. Lightning zigzags beneath threatening clouds, and the sea of barley heads ripples a little more urgently in the gathering breeze. I’m about to get wet. Very wet. But a short, sharp soaking is a small "

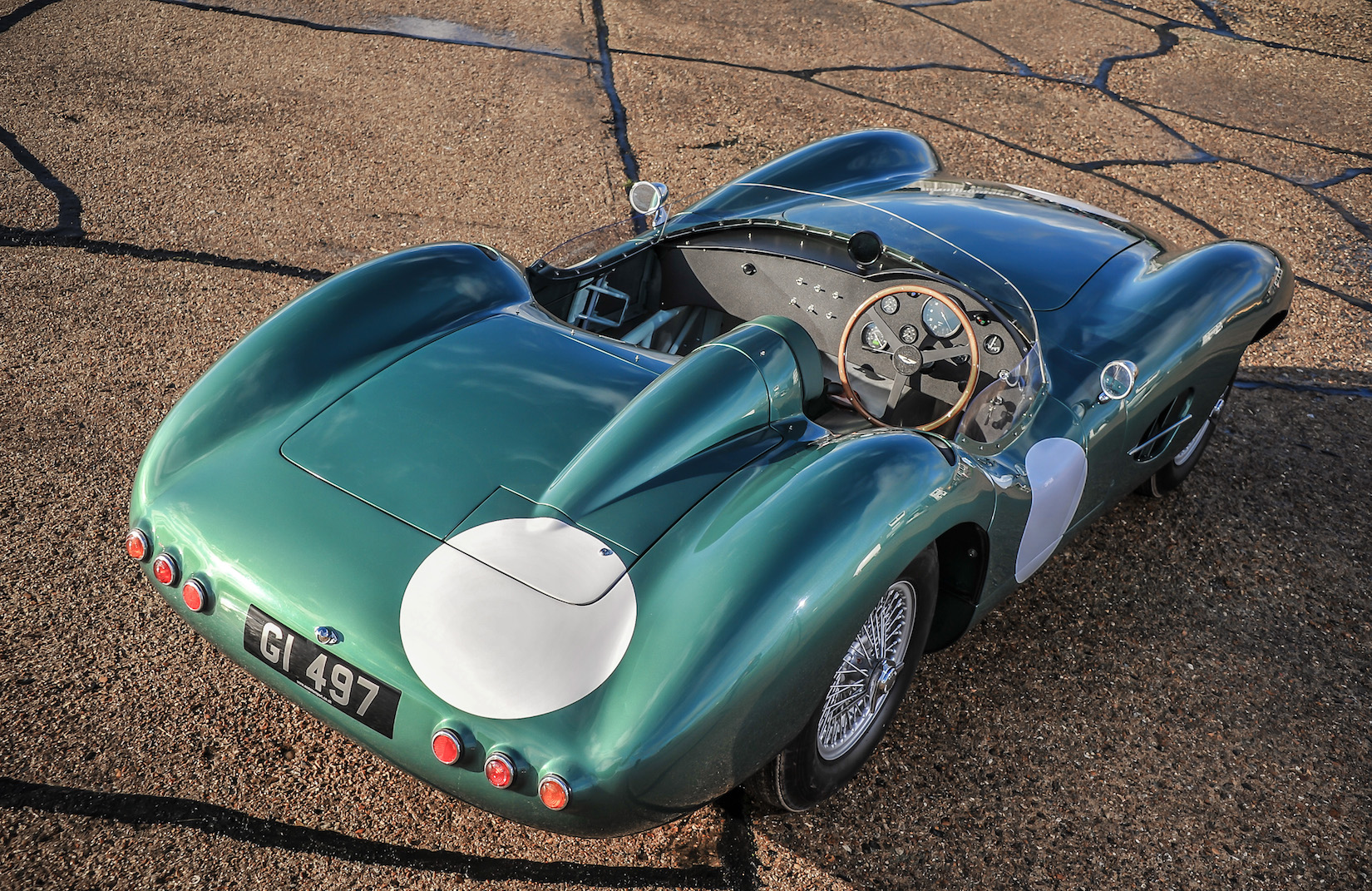

The legendary Aston Martin DBR1: reborn in Norfolk

Le Mans-winning Aston from the 1950s roars back to life as a faithful replica

At first glance, there is nothing unusual about Poplar Farm in south Norfolk.

Approached by winding country lanes, a traditional farmhouse nestles behind a row of trees, assorted outbuildings and sheds stretch away and fields of wheat and barley await harvest.

The only clue that something special is happening inside those outbuildings, that one of the most evocative racing cars in British history is being painstakingly recreated for enthusiasts across the world, is the presence on the long driveway of a skeletal display frame, almost the ghost of an Aston Martin DBR1.

For as well as a working farm, this is the home of AS Motorsport, where Andrew Soar and his team of engineers craft by hand an average of four faithful replicas a year of the most famous racing Aston of them all, the car that gave the marque its sole outright win at Le Mans in 1959 in the hands of Carroll Shelby and Roy Salvadori.

Fittingly, we visit Andrew a few days after he returns from his annual pilgrimage to the 24-hour race – a few days after the Aston Martin Vantage snatched a dramatic last-lap victory from Chevrolet in the GT class.

The cars he and three staff build in this most tranquil patch of countryside are worlds apart in design, engineering and power to the modern Aston but, according to Andrew, they are all the better for it.

“In modern cars, you’re insulated from the whole experience – you can’t explore the raw element or the edge of performance,” he says. “You’re just so removed from the whole experience really.”

That can’t be said of the ASM R1, which looks, feels and drives like the 1950s racer it emulates, a car described by Stirling Moss as one of the best-balanced cars he had ever driven.

“The weight is split 50/50 front and rear, and you can do some stupid things with the car and it doesn’t bite you,” says Andrew, who has driven the car in all weather and as far as Nice in the south of France.

Each car is built to order, ranging in price from £80,000 for a fibreglass body to £130,000 for aluminium, with build times from four to six months to eight to 12 months, depending on the body and exact specification.

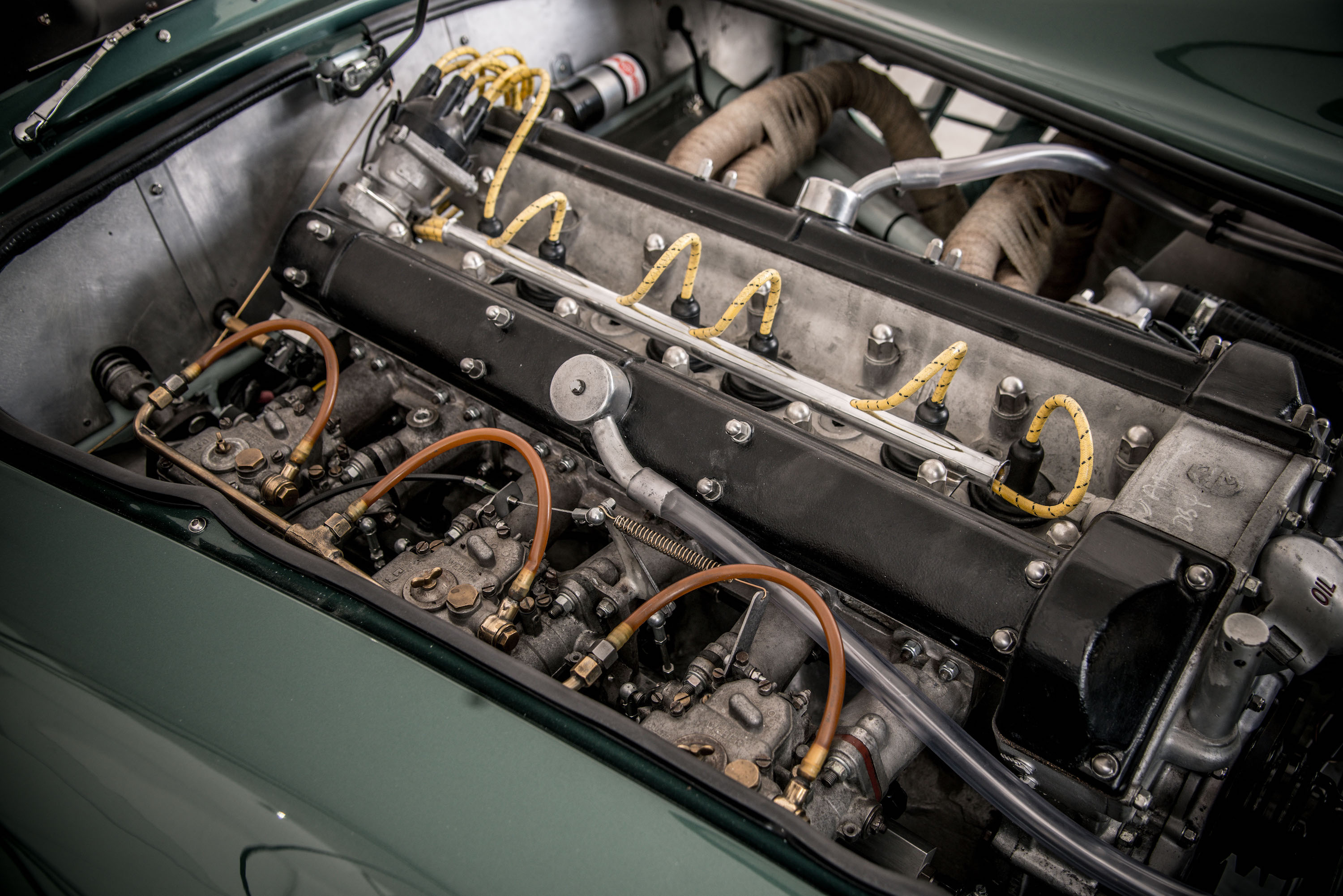

The basic engine used is a rebuilt 3.4-litre Jaguar straight six, producing up to 200bhp, though the demonstration car has the larger 4.2-litre unit, and some customers opt for a more expensive Aston engine, all married to a five-speed gearbox.

Customers can specify “any colour as long as it’s green”, although Andrew has had a request for blue from some Belgian clients.

“The Belgians seem to want dark blue. One of these did run in blue in the 1960s, but what will probably happen is people who are not clued up will say ‘is that a D-Type?’ and it might start to get a bit wearing after a while,” he says.

Including the five cars in various states of build dotted around the workshops, in nearly a decade 42 bespoke cars will have left Norfolk by the end of this year, bound for customers in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Gibraltar, Jersey and across the UK.

“We have a wide range of customers, people that can remember them in period and want to emulate their heroes, and people that just like the idea of it and the history behind it,” says Andrew.

“It’s something different. There have been one or two pension release situations where they want to spend it on something fun, plus the serial car investors and collectors. We have customers in their 40s up to those in their 80s.”

Andrew grew up on the farm at Bressingham, near Diss, and spent his formative years “playing with machinery and tractors”, and old Morris Minors.

“My older sister had a Morris Minor bought for going away to uni,” he remembers. “A second and third one were bought for spares. I annexed one of them – I was still at primary school then, learning how to syphon petrol from my dad’s car so I could drive it around the fields.”

In a few weeks’ time, he will return to those fields to spend long summer afternoons piloting a combine harvester up and down acre after golden acre.

It’s a job he enjoys, a solitary occupation reaping the rewards of a long growing season, with just his dog Nelly – scouting for hares – for company.

“I’ll come in in the morning, sort a few things out at the workshops, and then drive up and down the field with my dog,” he says. “The car business is full time now, but I still help out around the farm.”

Andrew was always intrigued by the engineering aspect of farming, honing his skills repairing tractors “partly out of necessity to keep costs down”, learning blacksmithing with Billy the Smithy, and electronics found on GPS harvesters.

“I used to go to the local blacksmiths to get stuff fixed – it made sense to help him finish whatever he was working on and I spent quite a lot of time with him,” he adds.

On leaving school, Andrew studied agricultural engineering at college, then became a workshop technician before moving into lecturing in the technical department, remaining for 10 years and meeting his future wife in the process.

Always self-employed – “I always say I’ve never had a job” – Andrew worked as a consultant in the construction and engineering sector, specialising in the safety and operation of heavy plant, before returning to the farm after a stint in America.

The seeds of the current business were sown when Andrew bought and built a Cobra 427 kit car.

“I was motivated to get it on the road, and spent a lot of time tinkering with it to sort out various issues – different engines, gearboxes, and suspension developments,” he says.

“Through networking with the kit car community I started doing work for other people. The workshop we use now was originally converted by my cousin, who was a mechanic and provided support to the farm.

“I had access to his facilities and when he moved out I graduated into there. It was the natural place for me to gravitate to.”

With the Cobra complete, and refined, Andrew spotted an eBay advert that would change the course of his business, and breathe fresh life into an automotive icon.

In 2007, the now defunct ARA Racing, run by Ant Anstead, was offering a replica DBR1 bodyshell and chassis for sale.

“I bought it as a personal project – it was a beautiful thing, quite apart from the fun of building it,” says Andrew.

“I thought if I took it to shows, with a bit of networking I would be able to bring in more specialist sports car and kit car work. I also thought I could do some consultancy work for ARA, but then it transpired that the whole project was for sale.

“I could see possibilities there and I thought ‘in for penny, in for a pound’. There were three or four manufacturers of the C-Type and D-Type replicas and they all have a market, enough to make a living.

“I thought that if we’re the only people doing this product we should have a good chance. It was just something that happened along, and the car has sheer beauty, plus a bit of raw power to it and a lot of history.”

The project purchase came with a stand at the Goodwood Revival festival, and an order for a part-complete, and part paid-for, fibreglass car with an Aston Martin engine.

“I decided to build the car for the amount outstanding and build it to the designs specified, using my own finances before I ask for any money,” says Andrew.

“I was in touch with the customer and got all the way to paint stage, and then it all went quiet. No contact from him at all. We had that car available for a few shows, and then I sold it at Bonhams Auction in 2008.”

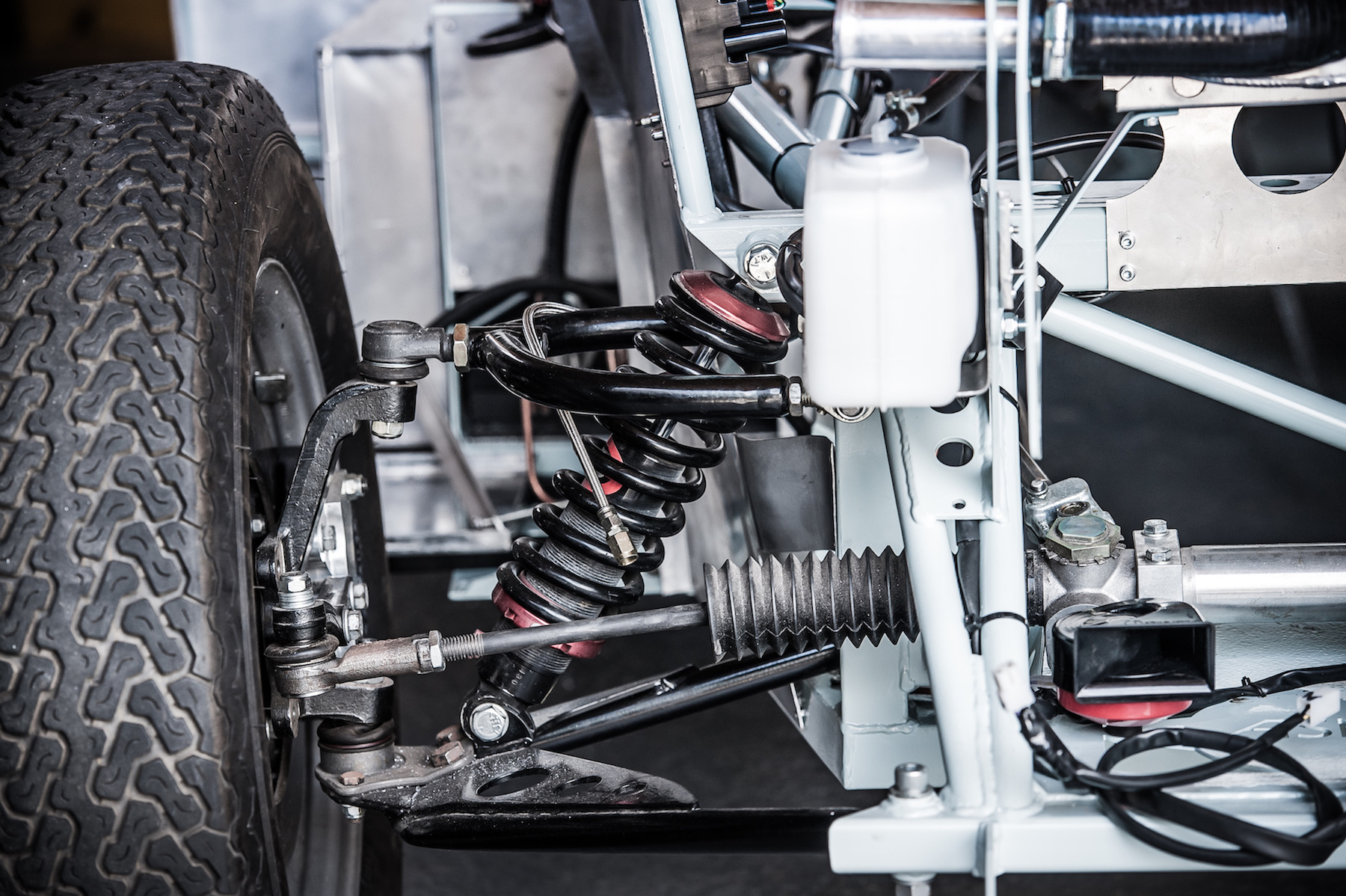

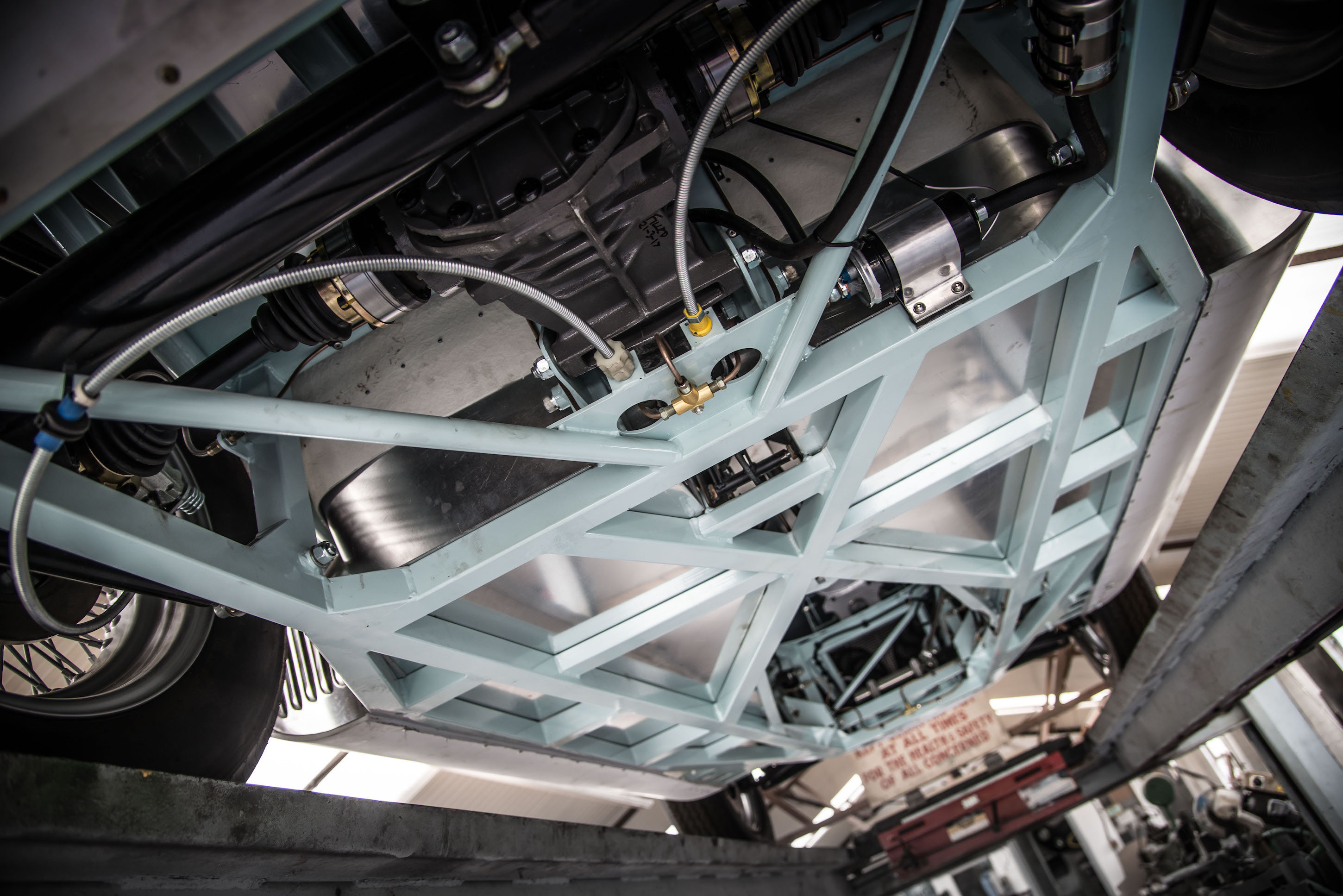

Orders started to come in, and Andrew undertook significant development work to improve the suspension design, brake packages, geometry revisions and structural improvements, with a timber jig developed using 3D computer technology to help fashion an authentic aluminium body shape.

Upgrades to the fibreglass car have included aluminium boot, bonnet and doors, and a major investment in aluminium tooling has helped improve quality and reliability, and reduced the time taken to build each car.

“We’ve constantly been developing and improving the car and our processes,” says Andrew. “Rather than sitting back on our laurels and just thinking we are getting quicker and quicker, let the money roll in. We’ve used that time to think about other areas we can improve. Nothing’s ever perfect.”

About half of customers opt for the aluminium body shell, despite the £50,000 premium, while all cars developed in the past two years have featured a bespoke multiport fuel injection system.

“We haven’t built a carb car for a couple of years,” says Andrew. “Everyone likes injection. The key is driveability, and it delivers smooth, linear, controllable power. You’re also future proofing yourself against any future emissions regulations against so-called dirty cars.”

Dashboard layout, seats, nose-cone colour and other trim can be specified by the buyer, with one aircraft enthusiast opting for cock-pit style instruments.

“Some of the switches proved quite tricky to source, as there are not many people that make them,” says Andrew, who uses parts from donor cars to secure an age-related number plate.

“We prefer to buy a whole donor car so you get matching numbers and documents, which helps with registration.”

The standard car produces between 250lb ft and 275lb ft of torque, resulting in lively, tractable performance from a body weighing only 900kg.

“We’ve never done a 0-60 test, but it’s quite pacey,” says Andrew. “It’s quite fun to be in something that looks old and cronky, then you dip past a modern car and disappear off. That’s main ethos behind the cars – to build something that works and is, above all, fun.

“At the Oily Rag Club Sprint event at Woodbridge Airfield it was doing comparable times to a hotted-up MX-5, and I’ve also been hillclimbing at Prescott and got it down to 57 seconds, which is not bad for an amateur driver in a standard set-up road car. I could probably get a second off that with a bit of courage.”

Although most are used as road cars, like the DBR1 its modern recreation is designed to be raced, and Andrew and his team have built a handful of cars to MSA regulations.

Shows remain the company’s staple marketing tool, but Andrew shies away from typical car sales tactics.

“I don’t pressure people to buy the cars,” he says. “If you do that and spend six months building it and they then don’t want it…people either want one or they don’t.

“They certainly attract a lot of attention on the road – you’ll be going along the motorway and spot a car coming past, then it gets into your blind spot and they don’t reappear because someone in the passenger seat is taking photos.

“It’s not why we build them, but maybe it’s why some people buy them.”

There’s a long and distinguished link between the slowest and fastest vehicles on our roads, those trundling tractors and the sports cars that could overtake them in a flash.

Ferruccio Lamborghini, Ferdinand Porsche and David Brown, the man who saved Aston Martin, all cut their engineering teeth on agricultural vehicles before giving the world some of the finest cars ever made.

Andrew Soar, farmer, agricultural engineer and now sports car manufacturer, is adding his own footnote to that illustrious roll-call.

The legendary Aston Martin DBR1 lives on, reborn in rural Norfolk and bound for all corners of the globe.

See the full specifications available here.

Read what it’s like to drive the ASM R1.

Gallery

Photos by Simon Finlay.

CLICK TO ENLARGE