"Did you play Top Trumps as a kid? And yes, I mean the car kind: was there any other? Of course you did. And the same instinct that lit your little heart when you saw you’d been dealt, say, "

The Chimaera of Speed

The perfect illustration (below) of the glorious absurdity of the very, very fast car. The Bugatti Veyron will do 253 miles per hour. But it can’t do 253 miles in an hour, because at that speed its fuel consumption is so voracious that it will drain its tank after just fifty miles. You’ll have covered the distance from London to Brighton in twelve minutes, but stopping for petrol five times for every hour’s driving might get to be a drag.

The Veyron is not alone, of course. The 200mph car is probably a complete chimaera; to our knowledge, nobody has ever tried to drive a production car at 200 miles per hour, for an hour. Almost all the cars that make the claim would need to be towing an oil tanker to do it, and that would knock their speed a little.

And it’s all academic anyway. The combination of circumstances that allow you to do a really big speed in a road car are so rare as to make the proportion of very fast cars that have actually been driven at very fast speeds incalculably small. Forget the law: you’re almost certainly going to have to break it. The real problem is distance. Plainly, as a car’s speed increases, its rate of acceleration declines; you might get from zero to sixty in three-and-a-bit seconds, but getting from 190mph to the double-ton might take a minute as your car reaches the very limit of its abilities. Finding a road sufficiently long and straight and clear is almost impossible, and finding the nerve is even harder.

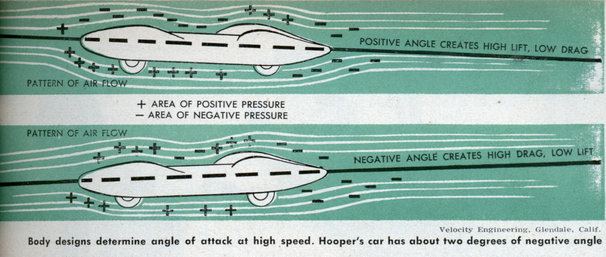

So why are we so hung up on top speed? Once, there was a genuine engineering benefit; the advances that made cars go faster, such as aerodynamics and more efficient engines, and stay stable and stop again, such as better brakes and suspension, filtered down to ordinary cars. That’s no longer the case; we’ve learnt pretty much all we’re going to learn, and the extra few miles per hour that now make a car the fastest in the world are eked out with extreme engine tuning and otherwise utterly impractical aero and suspension settings.

The Veyron did bring some benefits. Ferdinand Piech, the Sauron-like mastermind behind the Volkswagen group used the project as a trial-by-fire for aspiring engineers; if they could hit the almost impossible targets he set for the car – 400km/h, 1001 horsepower, one million euros – their careers were assured, and they’re now working on the Polos and Golfs the rest of us drive. But more often, being cajoled into doing a huge speed makes a car worse in normal driving. Off the record, Bentley engineers admit that making the Continental GT do 200mph left it hopelessly overspecified and overweight at a crushing 2.4 tonnes.

But even if you don’t actually want it, and never get the chance to use it, a big top speed appeals to anyone who ever played Top Trumps as a kid. It sells cars, and it sometimes prompts even the most revered of carmakers to massage the figures a little. A car’s top speed can be calculated with a fairly simple equation, making it easy to disprove some of the more ludicrous claims. You only need a car’s power, frontal area, drag coefficient and rolling resistance to work out how fast it will go with the right conditions and gearing.

But the really striking thing is the relationship between speed and power. To make a car go faster, the extra power required is proportional to the cube of the extra speed. Put simply, to make a 180mph car do 200mph – a speed increase of 11 per cent – you need 37 per cent more power. It’s difficult, expensive, and much easier to fib.

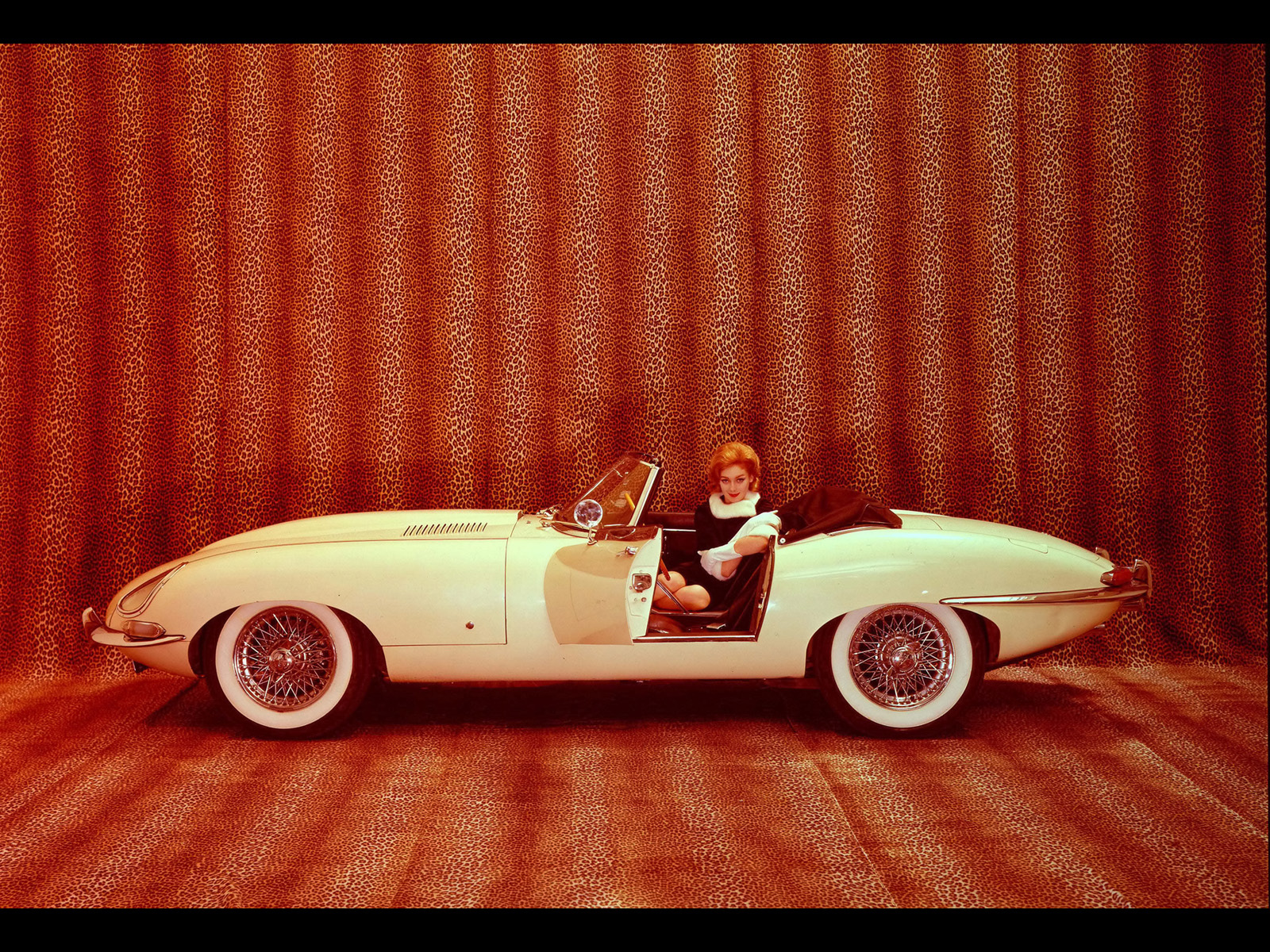

Could this car really breach a ton-fifty?

The pre-production Jaguar E-Type that became the first road car to hit 150mph in 1961 almost certainly had a little help from the competition department; subsequent tests couldn’t replicate it. The Ferrari F40 was the first credible production car to claim a top speed over 200mph, boasting of 201.3mph at its launch in 1987, but to our knowledge this has never been independently verified. Maximum respect to Porsche for eschewing Italian willy-waving and NOT claiming 200mph for its 959, launched at the same time as the F40. It would have been a killer marketing line, but Porsche knew it wasn’t true. It claimed 197mph instead, and that’s exactly what the 959 did in an independent test.

In the same month that Ferrari made its 200mph claim for the F40, Phil Hill and Paul Frere timed the Ruf CTR ‘Yellowbird’ at 211mph for US magazine Road and Track, and it did 213mph the following year at Nardo. The CTR – Ruf’s reworking of the Porsche 911 Turbo – was made in small numbers compared to the 1315 F40s built but it still qualifies as a production car, Ruf having been granted manufacturer status by the German government six years previously. This tiny, bespoke carmaker beat the best in the world to make the first production car to prove it could do 200mph.

Ferrari was caught out again with the F50: it claimed 202mph, but the lease under which all 349 were sold specifically forbade independent speed tests; when a US mag finally managed to test one it did ‘only’ 194mph. Ferrari learnt its lesson; the Enzo will do all of its claimed 218mph.

The Enzo Ferrari lived up to its noble moniker

The Jaguar XJ220 and McLaren F1 posted genuine big numbers, but needed a little help. In ’92 the Jag had to have its catalysts removed to produce the extra 50bhp Martin Brundle needed to lift it from 210 to 217mph at the Nardo test track in Italy, or just over 220mph once the scrub effect of the high-speed bowl has been allowed for. Cue mass exhalation in Coventry; the car (just) lived up to its name. The McLaren F1 in which Andy Wallace set the long-standing 240.1mph record in 1998 needed its rev limiter removed to do it, though rumours still abound that the engine was ‘special’.

All these cars are extraordinary, covetable, engineering marvels. But perhaps our obsession with top speed is passing. There may never be another car like the Veyron: global recession, emissions regulations, social opprobrium and dwindling oil supplies mean we’ll have to get our kicks elsewhere, and the new technologies that replace the internal combustion engine might simply be incapable of propelling a car that fast. But do you really care that the all-electric Tesla Roadster will do ‘only’ 125mph, when you’ll seldom get close to that in normal driving, and its acceleration to 100mph is so – well – electrifying, and produced with zero emissions or guilt?

CLICK TO ENLARGE

We've had the speed era the next big challenge facing engineers is replacing oil as the energy source. This of course means finding a sustainable clean energy source for the masses to maintain personal transport.

If the result is as long in coming as our speed accomplishments we may find ourselves using horses again.

Sort of reminds me of where we are today with air travel and the demise of Concorde, ie going backwards.

Found something today – in fact Mike the editor of this fine 'zine pointed it out to me, that encouraged my instinct that speed will never pall in its significence for many of us.

“Some people will tell you that slow is good – but I’m here to tell you that fast is better. I’ve always believed this, in spite of the trouble it’s caused me. Being shot out of a cannon will always be better than being squeezed out of a tube. That is why God made fast motorcycles, Bubba…

— Hunter S. Thompson

I think to say your view of fast is better is somewhat arrogant. A more rounded view would consider both fast and slow as having equal attributes.

The point I was trying to make is after a century of trying to go faster whether on the ground in the air or on the water we are facing new challenges in the coming century of just staying mobile.

Energy efficiency will determine the performance of future cars and with increasing congestion fast will be less significant than in the previous century.

Humans will always reach for the ultimate. That's why we'll always have supercars.

Just imagine if we could harness this incredible 'inventiveness' to improve mundane (but terribly expensive) things like houses….what would that be like?

Speed + cars + public roads may have a limited future in overcrowded places, but there is no reason why people in Alaska or Australia or Argentina won't continue to race around, getting quicker every year. It's just that they won't be tuning Fords or GM products but maybe a locally produced special. Running on guava husks. Emitting sand and white spirit.

Just imagine if we could harness this incredible 'inventiveness' to improve mundane (but terribly expensive) things like houses….what would that be like?

Speed + cars + public roads may have a limited future in overcrowded places, but there is no reason why people in Alaska or Australia or Argentina won't continue to race around, getting quicker every year. It's just that they won't be tuning Fords or GM products but maybe a locally produced special. Running on guava husks. Emitting sand and white spirit.

Dear Sir/madam

While I agree with most of your article I would like to point out that electric cars are not

Emission free, they simply produce theyer emissions at the power station.

Regards. John May.

Dear Sir/madam

While I agree with most of your article I would like to point out that electric cars are not

Emission free, they simply produce theyer emissions at the power station.

Regards. John May.

Someone, Finally! Where do you think elektricity came from?